Hong Kong’s HIV problem: prejudice is the real malady in a society where intolerance is still prevalent - and accepted

Anson Au says the cutbacks in government funding for HIV prevention and treatment in the face of rising infection rates among gay men point to an unpalatable truth: discrimination against sexual minorities is tolerated in Hong Kong

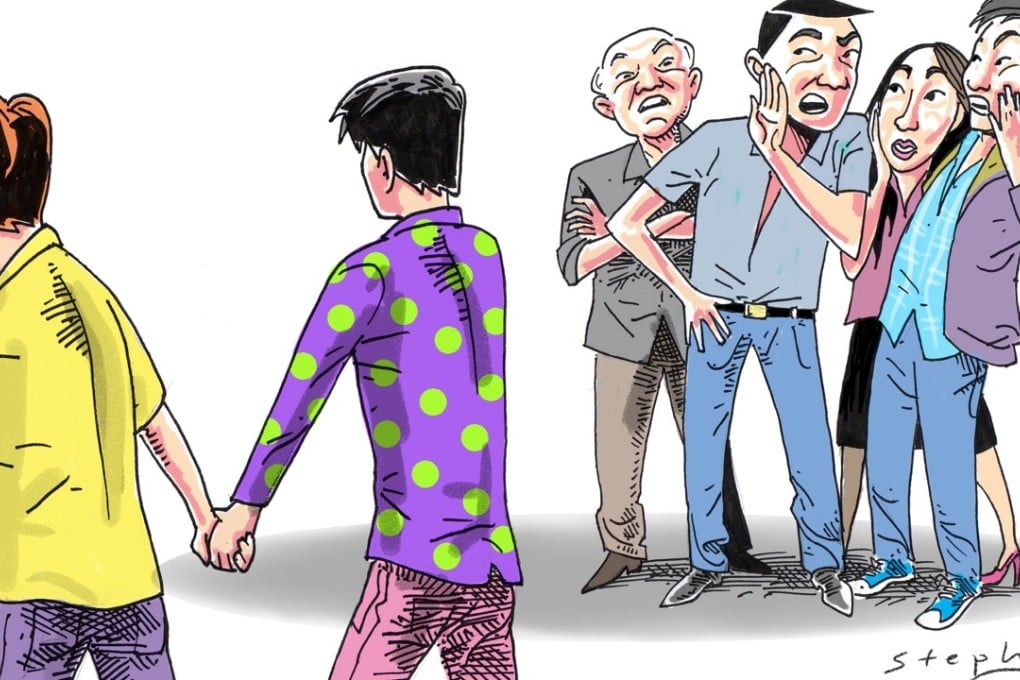

We appear to be bordering on a health epidemic for HIV/Aids. Given the virus’ prevalence in men who have sex with men, the issue hasn’t earned much attention among the wider public, but where it has, it invokes much controversy and political rifts.

Watch: Showing support for gay rights with hugs in China

Conservatives are largely indifferent to the news. The refrain often goes: why should taxpayers pay for health care for people who “get sick by their own choice”? Why should the government give special treatment to sexual minorities?

Besides, we contribute our tax dollars to treatments for cancer and other diseases that are related to smoking, drinking, and other wilful lifestyle behaviour, yet we’re not up in arms over this.