Donald Trump is a master manipulator of bias. The trouble is, we go along with it

David Dodwell says the apparently common human tendency to believe we alone see the world as it truly is, without bias or error, can be – and has been – easily manipulated to undermine fact-based policymaking

Let’s imagine you are driving along a motorway at 80km/h. For sure, anyone driving slower than you is a senile idiot, and anyone that roars past you is a dangerous maniac. Because you have made a decision about the right speed for that particular piece of road, by definition, anyone driving faster or slower is driving inconsiderately or dangerously.

As the Financial Times’ Tim Harford observes, this is what psychologists call “naive realism” – “the seductive sense that we’re seeing the world as it truly is, without bias or error”.

“This is such a powerful illusion that whenever we meet someone whose views conflict with our own, we instinctively believe we’ve met someone who is deluded, rather than realising that we’re the ones who could learn something,” he wrote. Anyone who agrees with us is “thinking rationally” and “paying attention to facts”, while those who disagree are ignoring important facts, being “politically correct”, or seeking “peer approval”.

Harford recalls a famous 1954 study by psychologists from Princeton and Dartmouth of a football match between the two colleges. After the game, which had been more than usually violent, they took students from both colleges and asked them to count the fouls. Princeton students counted twice as many Dartmouth fouls as Dartmouth students counted – and vice versa. The researchers concluded: “Despite being shown the same footage, the students really did not see the same game.”

Daniel Kahneman concluded much the same in his brilliant Thinking, Fast and Slow: “We can be blind to the obvious, and we are also blind to our blindness.”

It seems our tendency towards bias is powerfully hardwired. A team of psychologists from Arizona State University, writing in this month’s Scientific American, noted three particular obstacles to “clear scientific thought” (aka bias): short cuts; confirmation or desirability bias; and social pressures.

Short cuts are the ways we deal with information overload: “When we are overwhelmed or are too short of time, we rely on … group consensus, or trusting an expert.”

Confirmation bias is seeing what we want to see – in short, wishful thinking – or selectively remembering. Many times in my journalistic career, I have suffered the frustration of readers forgetting what I have written about – because they disagreed or were uncomfortable with unwelcome facts and conclusions. People selectively remember what they agree with, and discard the rest. They are reading not to be informed, but unconsciously to gather anecdotes that support and insulate their prejudices.

Then there are peer group pressures that persuade you to agree with your tribe, right or wrong. The fear of ostracism is severe: “Holding an opinion different from other group members, even a correct opinion, hurts emotionally,” the Arizona State team noted. Ostracism apparently activates the same region of the brain that flares when we experience physical pain.

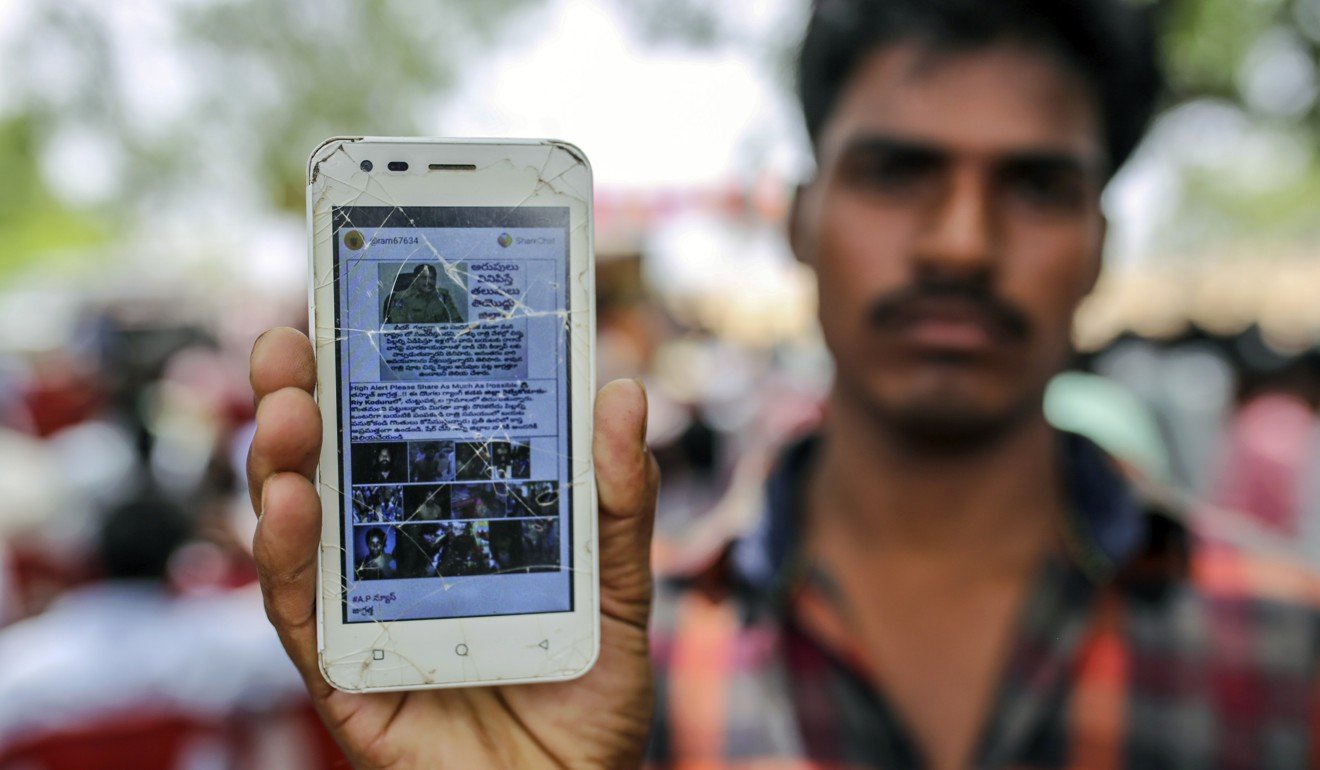

Not only is bias inbuilt, but it is easily and powerfully manipulated – with Trump a master manipulator. Devices range from sowing doubt and seeding simple untruths, to weaving entertaining distractions, and Trump has mastered them all.

Perhaps the best single example of the power of sowing doubt was the decades-long campaign by US tobacco companies to fog the scientific consensus over the link between cigarettes and cancer. As one famous internal memo noted: “Doubt is our product.” Robert Proctor, the Stanford historian who studied the tobacco campaigns, created a new word to capture the tobacco companies’ beguiling success – agnotology, or the process by which ignorance is deliberately produced.

Seeding doubt is made easier by the reality that simple lies are much more persuasive than complex truths. As Tim Harford notes: “Once we have heard an untrue claim, we can’t simply unhear it … repeating a false claim, even in the context of debunking that claim, can make it stick.”

Other factors steering people away from facts and into the lap of bias are the reality that facts are often boring, and that the truth often feels threatening.

Watch: Trump-Kim ‘deal’ – the movie trailer

And with Trump’s venal politics steadily gaining ground, it is distressing that no ready responses come to hand. As Harford concludes: “We journalists and policy wonks can’t force anyone to pay attention to the facts. We have to find a way to make people want to seek them out. Curiosity is the seed from which sensible democratic decisions can grow.”

Or is that his desirability bias kicking in – simple wishful thinking?

David Dodwell researches and writes about global, regional and Hong Kong challenges from a Hong Kong point of view