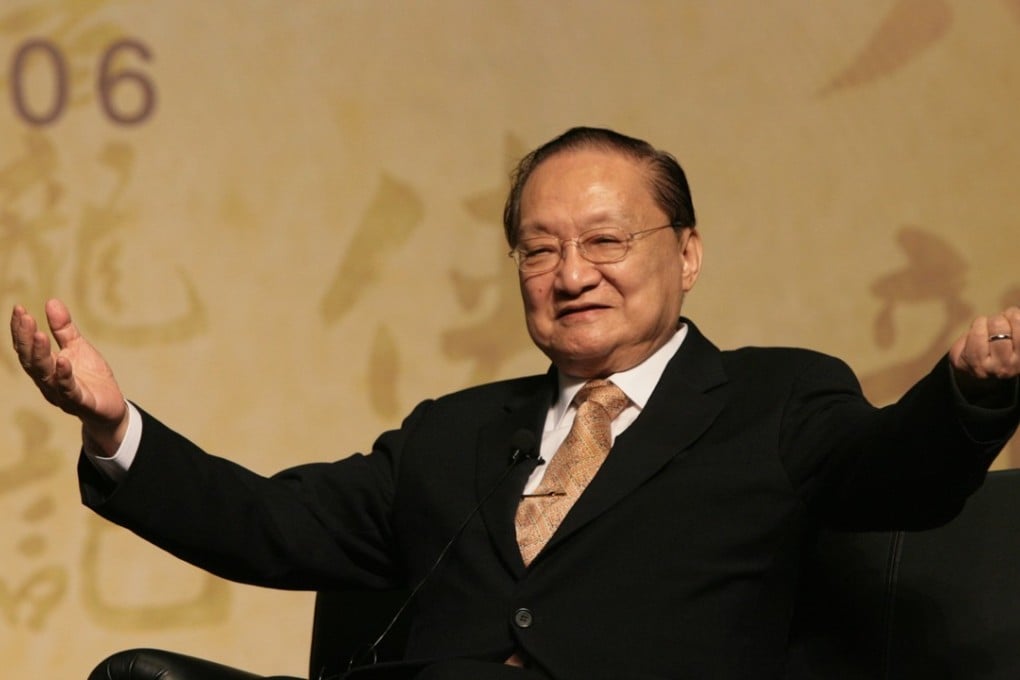

My Take | Television, not the Brits, made Louis Cha 'Jin Yong' a household name

- The death of the legendary martial arts novelist has been met with tributes from all sections of society and not a little political point-scoring

It’s the sign of a great artist that people from the left and right will try to claim him as one of their own, and that people will use his work, in life as in death, as a prism to reflect on society’s conflicts and controversies.

So it’s no exception with wuxia novelist Louis Cha Leung-yung. Tributes have been pouring in since his death was announced on Tuesday. Expressions of admiration are almost universal. But implicit in some of the eulogies is political score-taking among the local literati.

While acknowledging his literary legacy, veteran columnist and confessed Anglophile Chip Tsao made a controversial statement in an interview with Ming Pao Daily News, the newspaper Cha co-founded in 1959.

“Without the freedom provided under British colonialism, Jin Yong’s [Cha’s pen name] achievements would not have been possible,” he said.

Meanwhile, Lingnan University historian Lau Chi-pang said Cha might not have achieved literary success today because of the city’s anti-mainland sentiments. Cha was born and educated on the mainland but moved to Hong Kong as a newspaperman shortly before the 1949 communist takeover.