Opinion | Hong Kong should reject air quality goals that don’t put public health first

- The government should provide scientific evidence to back up its claim that society will be better served by having a tighter limit on the key pollutant PM2.5, but also allowing many more days when such a limit can be flouted

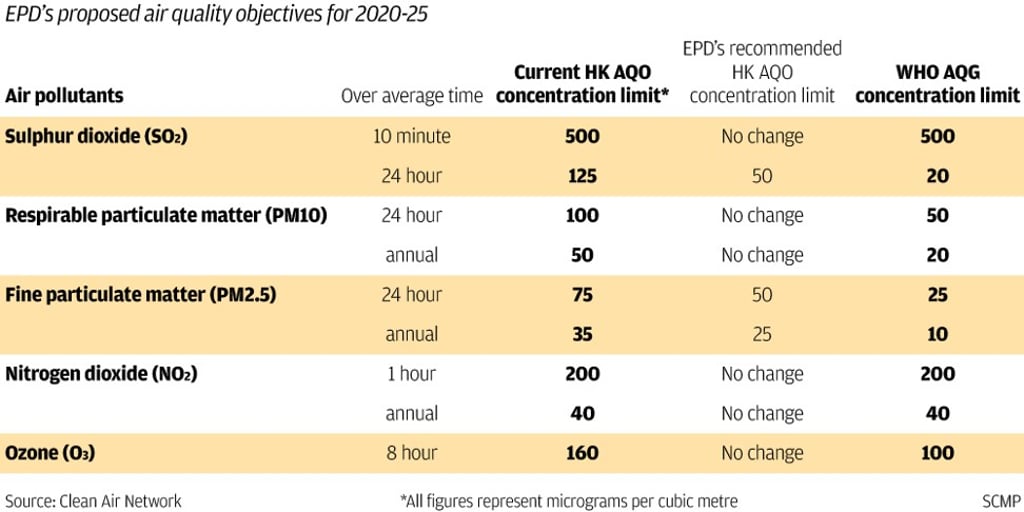

These “air quality objectives” set a concentration limit for each air pollutant, and it is the job of the government to ensure our air quality stays within these limits. Unfortunately, the limits have always been much looser than the standards recommended by the World Health Organisation. Among the standards set for five major air pollutants, only one (for nitrogen dioxide) is currently as stringent as the WHO’s guidelines.

At first glance, the new standards – to take effect from 2020 to 2025 – are an improvement from the old. But that’s far from the truth.

One of the most controversial parts in the proposal is a plan to tighten the concentration limit for fine suspended particulates (PM2.5), a pollutant which has been classified as a carcinogen by a WHO agency, while greatly relaxing the number of times in any year that the concentration limits can be exceeded. Under the current standards, PM2.5 is allowed to exceed the concentration limit nine times each year. The government is proposing to increase that number to 35.

Here’s the logic, if you can believe it. In an air quality forecast for 2025, the government projected that the level of PM2.5 would be exceeded 33 times, based on the proposed limit. Hence, the way to ensure all targets are met is to simply allow for plenty of exceptions. So instead of enacting more measures to control emissions, such as encouraging a switch to electric vehicles, the government has found a “short cut” to get Hong Kong to meet its air quality objectives – by allowing exceptions to the standards. How convenient!