Shades Off | There’s money in property, and that’s good enough for Hong Kong

- Officials talk of diversifying the economy, but our tycoons, many of whom made their fortune in real estate, are admired for their success and indispensable to the government for their contribution to its coffers. Talk will remain just talk

I’ve little doubt what the typical Hongkonger would do if he or she won a lottery jackpot. Firstly, they would be secretive about who they tell for fear of having to unnecessarily part with cash. A portion would probably go to charity, but the biggest chunk would go into buying property – a large flat for the lucky winner, the rest for lifelong rental income. It’s an idea that flies in the face of good financial investment advice, which stresses the importance of diversification to limit risk.

The logic is that there is no better investment than property, which will usually go up in value and if down, only momentarily before resuming the march upwards. Americans and now Australians can relate otherwise and, of course, there is Hong Kong’s own economic downturns during the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in 2003 and the Asian economic crisis of 1998 to also prove otherwise.

But memories are short and anyway, the government, for all its talk of the future lying in innovation and technology, is firmly wedded to the same thinking.

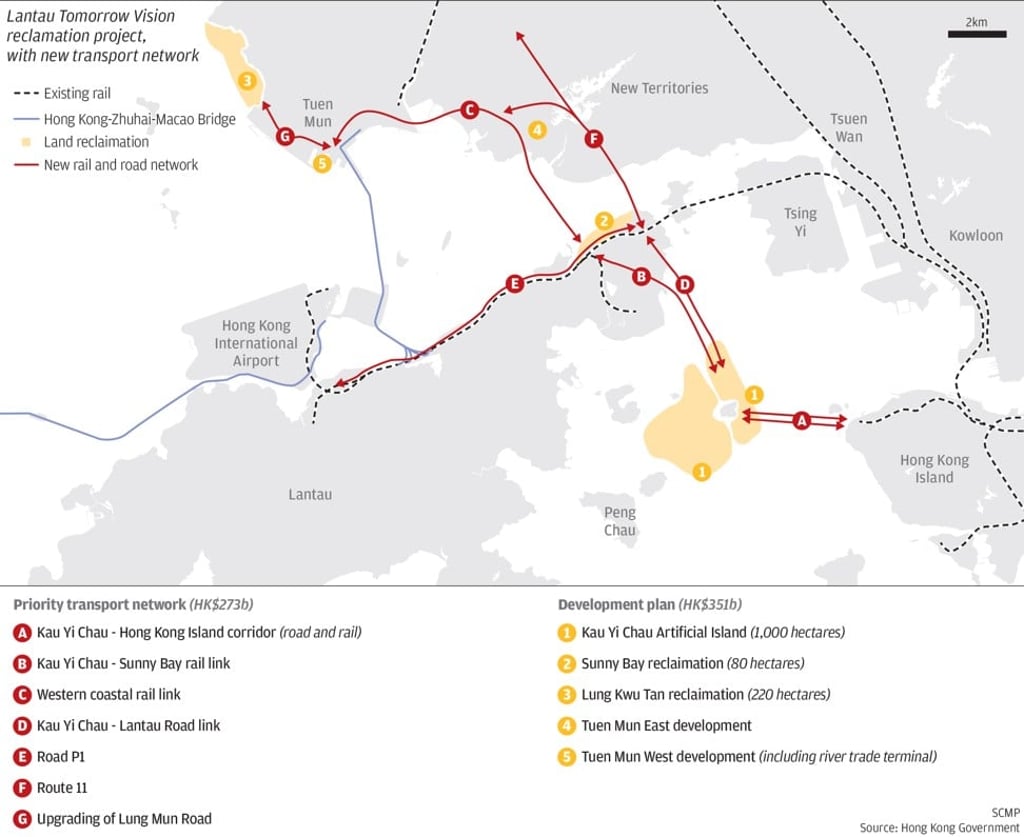

Land and its use is, after all, where the bulk of government revenue comes from, as has been the case since the British colonial government hit on the idea of reclamation to create extra revenue in the latter half of the 19th century.