On ‘comfort women’ and Japan’s war history, Abe’s historical amnesia is not the way forward

Jeff Kingston says the anniversary of the Kono Statement, in which Japan apologised for its treatment of ‘comfort women’, is a reminder that the country must reckon sincerely with its past if it wants to build a new future with its neighbours

Yohei Kono, the chief cabinet secretary, affirmed that “the then Japanese military was, directly or indirectly, involved in the establishment and management of the comfort stations and the transfer of comfort women. The government study has revealed that in many cases they were recruited against their own will, through coaxing, coercion, etc, and that, at times, administrative/military personnel directly took part in the recruitments. They lived in misery at comfort stations under a coercive atmosphere … Undeniably, this was an act, with the involvement of the military authorities of the day, that severely injured the honour and dignity of many women.”

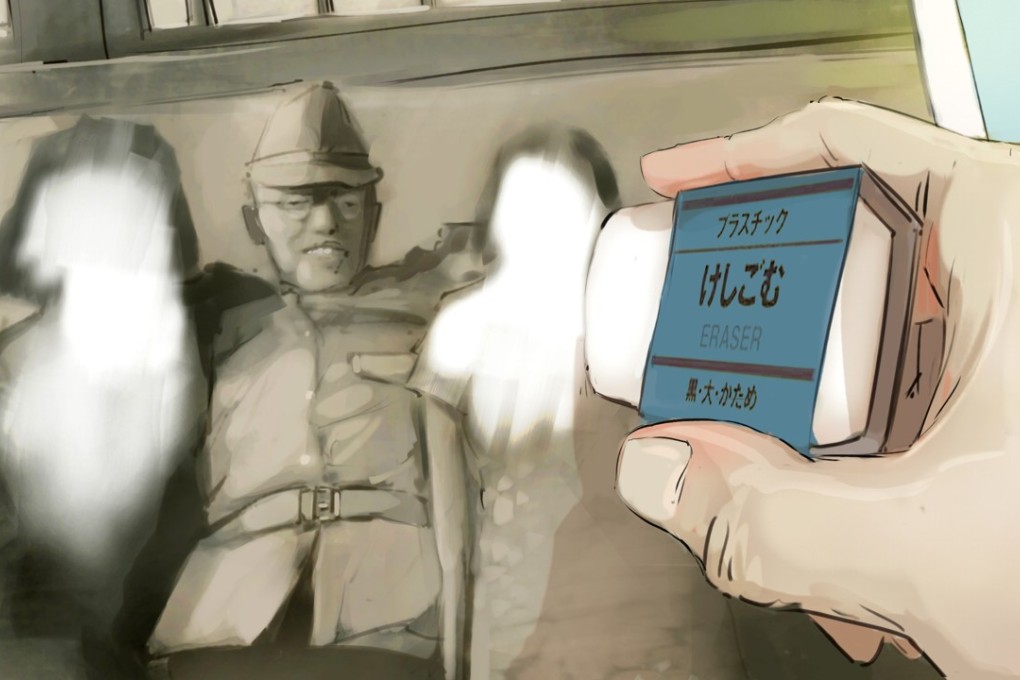

Abe is closely associated with a revisionist whitewashing of Japan’s shared past with Asia and since entering politics in 1993 has been active in various Diet groups lobbying for this agenda. He has persistently denounced and undermined the Kono Statement because the forthright reckoning it embraces is the antithesis of the revisionist history he stands for.