China-India rivalry opens up a new cultural front: state-sponsored vs spontaneous art

- John Zarobell says that much as US abstract art once competed with socialist realism propaganda, India’s and China’s competing visions for art are now vying for cultural influence

As globalisation has distributed economic benefits around the world more broadly, emerging economies are stepping up to express their role as actors in the global sphere.

While China is shoring up its sphere of influence through economic partnerships, its leaders launched a five-year plan to build 3,500 museums in five years; they completed this in three years in 2012 and have added hundreds every year since. There is a hint of civic largesse, but China is also signalling its cultural centrality, aiming to demonstrate the enduring edifice of Chinese civilisation and the authority it confers on the Chinese people and state to rule over an ever-widening domain.

India, among rising global economies, can make similar claims to global centrality and a case for global significance as a producer of culture. Because India does not have the same state resources devoted to cultural institutions as China, museums have not played a central role. Nonetheless, one private initiative has sought to put Delhi on the art world map.

The Kiran Nadar Museum of Art is built around the private collection of a single individual with the goal of leaving a large impact. Thanks to the funding of touring exhibitions and catalogues, this museum has provided a broader spectrum of South Asian contemporary art than can be seen in most Western museums.

In the era of globalisation, the museum may no longer be the primary site for encounters with contemporary art, replaced by the biennial and the art fair. These two forms of festival, offering cultural riches to cosmopolitan elite and local inhabitants for a limited time, have proliferated due to their comparable flexibility. India arrived late to the biennial party, initiating its first, the Kochi-Muziris Biennial, in 2012.

This has attracted the attention of the art world and local government, but has not transmitted the same kind of cultural authority as more publicised biennials such as the Dhaka Art Summit and the Shanghai Biennial. Nevertheless, the artist-run Kochi-Muzriis Biennial has credibility in the art world because it does not aim for commercial promotion.

The India Art Fair, held annually in Delhi, is another story. Its focus is commercial and self-promotional and, in recent years, the fair has become notable for hosting more visitors than any other art fair in the world. The fair, like the biennial and the museum, argues for the depth and vibrancy of India’s culture in a global market.

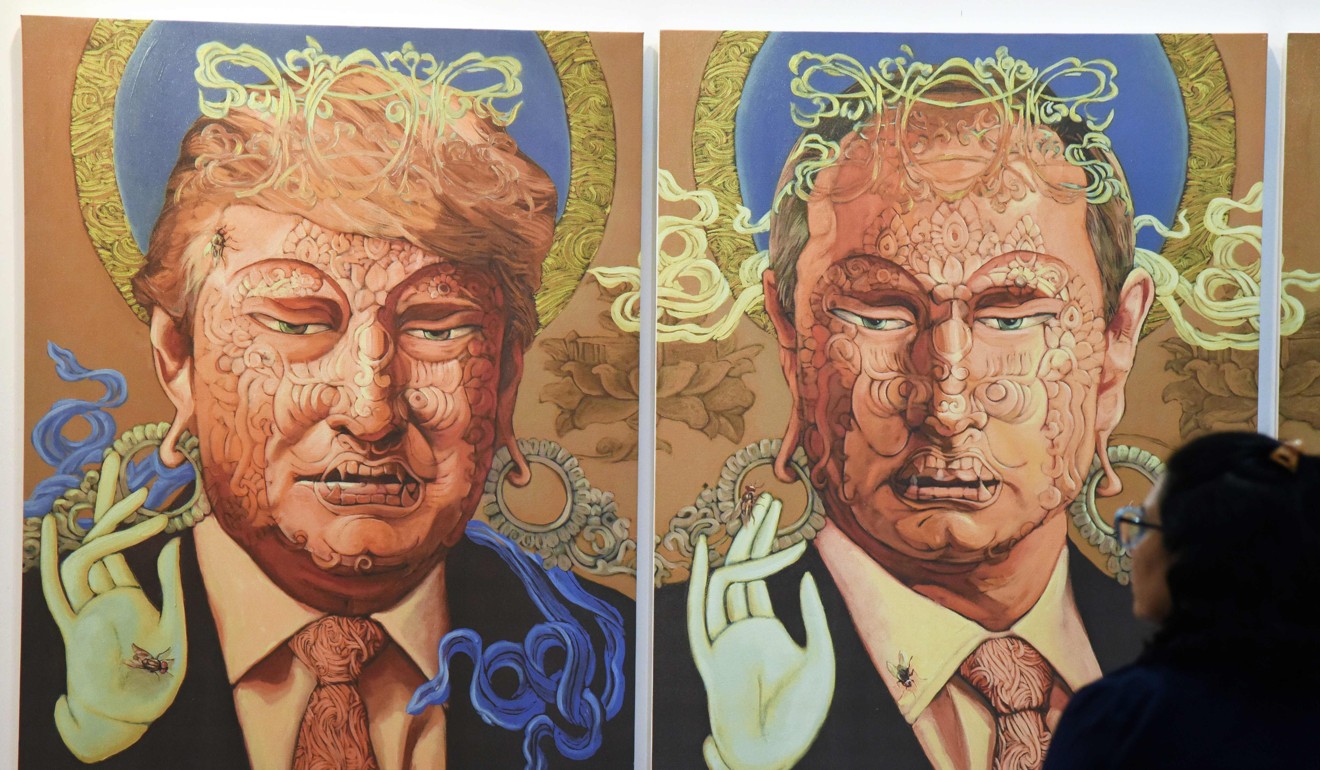

Of course, there is a long history of the use of art as soft power. The cold war was a stand-off of hard power – nuclear-weapons build-up to achieve mutual assured destruction – but actual battle lines were drawn through a series of proxy wars between the US and USSR and efforts to win over newly independent post-colonial nations to capitalist or socialist ideologies.

The US side deployed visual art to promote freedom of the American way of life. Artists in communist countries were expected to produce propaganda for the cause of the state, dubbed socialist realism by Western art historians, while American artists were free to experiment with whatever techniques they could conceive, leading to the development of abstract expressionism.

On the Indian side, the state does not see this form of soft power as worthy of investment, focusing arts expenditure on cultural heritage for the most part, but has produced a group of elites who seek to promote the image of India and South Asia as an incipient leader in the broader domain of global cultural production.

John Zarobell is associate professor and chair of international studies at the University of San Francisco. Formerly, he held the positions of assistant curator at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and associate curator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Reprinted with permission from YaleGlobal Online