Advertisement

Opinion | Rabies vaccine scandal reveals China’s tattered moral fabric

Lijia Zhang says the Communist Party’s violent discarding of traditional values, suppression of religion and later embrace of cutthroat capitalism has severely damaged social trust. The party has attempted moral campaigns since then but, as the Changsheng scandal shows, they have not worked

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

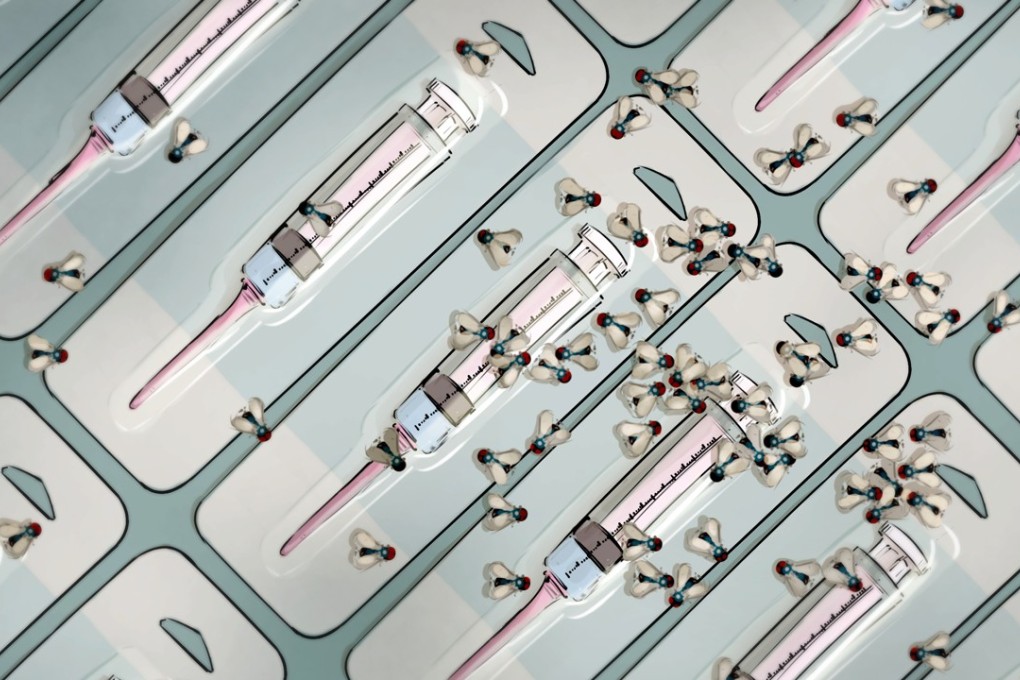

A major scandal is gripping China. Changsheng Bio-technology, the country’s second-largest vaccine manufacturer, was found to have fabricated production data and sold more than 250,000 substandard rabies vaccines. This has crossed a “moral bottom line”, Premier Li Keqiang said as he promised to “absolutely crack down” on such practices.

It is the latest public health and safety crisis to plague the country. Two years ago, the sale of expired vaccines came to light; and 10 years ago, China’s biggest-ever food safety scandal hit as millions of parents realised, with horror, that they might be feeding their babies poisonous milk.

Advertisement

Like other issues concerning children’s safety, the defective vaccine incident touched a raw nerve for Chinese parents and led to a public outcry.

Tens of millions expressed their anger and frustration on social media. Some demanded a thorough investigation and called for tougher regulation and more severe punishment. Others asked what kind of a society they were living in – and whether it had no morality at all.

Advertisement

Once again, the Chinese people are forced to ask the uncomfortable question: what has led to the moral decline of China?

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x