In Hong Kong, public consultations are effective – at keeping the public at bay

- Stephen Vines says the recent land supply consultation, which was pre-empted by the chief executive’s reclamation proposal, only deepens people’s cynicism over the government’s intention to engage the public

So far this year, as was the case last year, consultation exercises have been rolled out at a rate of two per month. Most of the 24 exercises launched this year were on issues affecting business. Some, such as the land supply consultation, were high-profile exercises but most are obscure and attract little attention, the consultation on radio spectrum for 5G mobile services being a case in point.

However, as Cheung points out, the government is likely “to exercise tight control over policies that it considers to be politically risky, and hence will be less inclined to genuinely engage the public in these areas”.

This looks like being polite academic-speak for saying that the government will engage but not be swayed when it comes to big issues.

Intense cynicism looms over this public consultation process. The government has succeeded in giving a bad name to the perfectly valid concept of public consultation.

The problem is, the government’s self-important officials appear to believe that they are the sole repositories of wisdom. Instead of appreciating that a vast resource of ideas and knowledge lies outside the administration, the consultation process sets out bureaucrat-devised options and does not entertain alternatives coming from those with hands-on experience on the related issues. If anyone knows of a single consultation exercise that has taken on board a substantive initiative from beyond the confines of the bureaucracy, I would love to hear about it.

The alleged consultation process is accompanied by the establishment of a long list of government advisory panels, which, again, are supposed to be engaging stakeholders and independent experts in the formulation of public policy. The reality is that these advisory bodies are dominated by government cronies, political appointees, moribund trade associations and, of course, the bureaucrats themselves. These bodies also often contain a sprinkling of rich kids, acting as proxies for their tycoon parents.

People who actually get their hands dirty in the world of business or anywhere close to the grass roots are thin on the ground.

Public consultation seems to have become a method of keeping the public at bay and erecting a facade of accountability. However, as the land supply exercise has shown, the outcome is more likely to be one of frustration and anger.

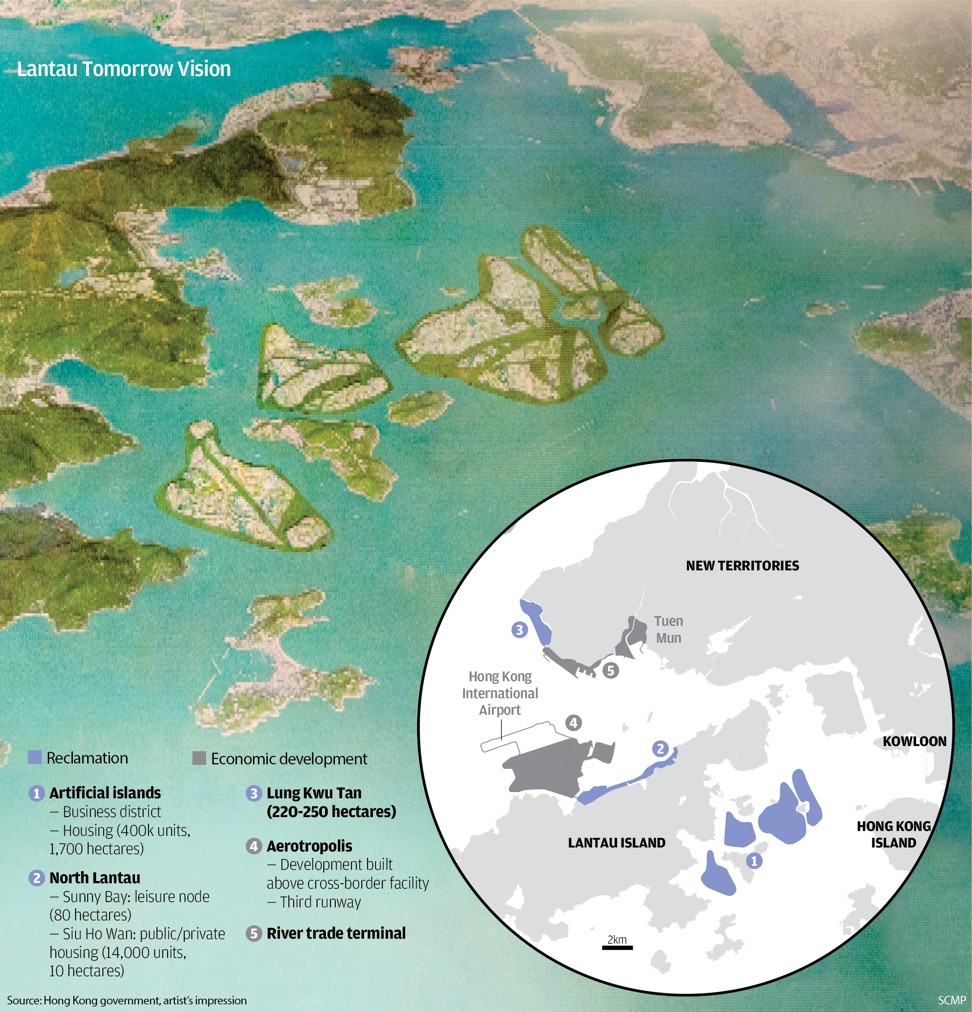

Watch: Why Carrie Lam’s Lantau reclamation plan is so controversial

This disquiet was also seen when the public was consulted over the appropriate level of the statutory minimum wage. The result was predictable. There was a stalemate and the exercise was dominated by associations claiming to speak for those who would be affected by minimum-wage levels, while people at the sharp end were nowhere near the proceedings.

Some readers may take comfort from this tendency of the government to favour corporate interests. The problem is that the favoured corporate interests tend to be those of the tycoon class, representing a fraction of the business community, which is dominated by small and medium-sized enterprises.

Stephen Vines runs companies in the food sector and moonlights as a journalist and a broadcaster