Diaoyu Islands dispute can be laid to rest if China and Japan accept joint sovereignty

- Andrei Lungu says the dispute over the islands is more about nationalism than practical reasons and has haunted relations between the two countries for too long

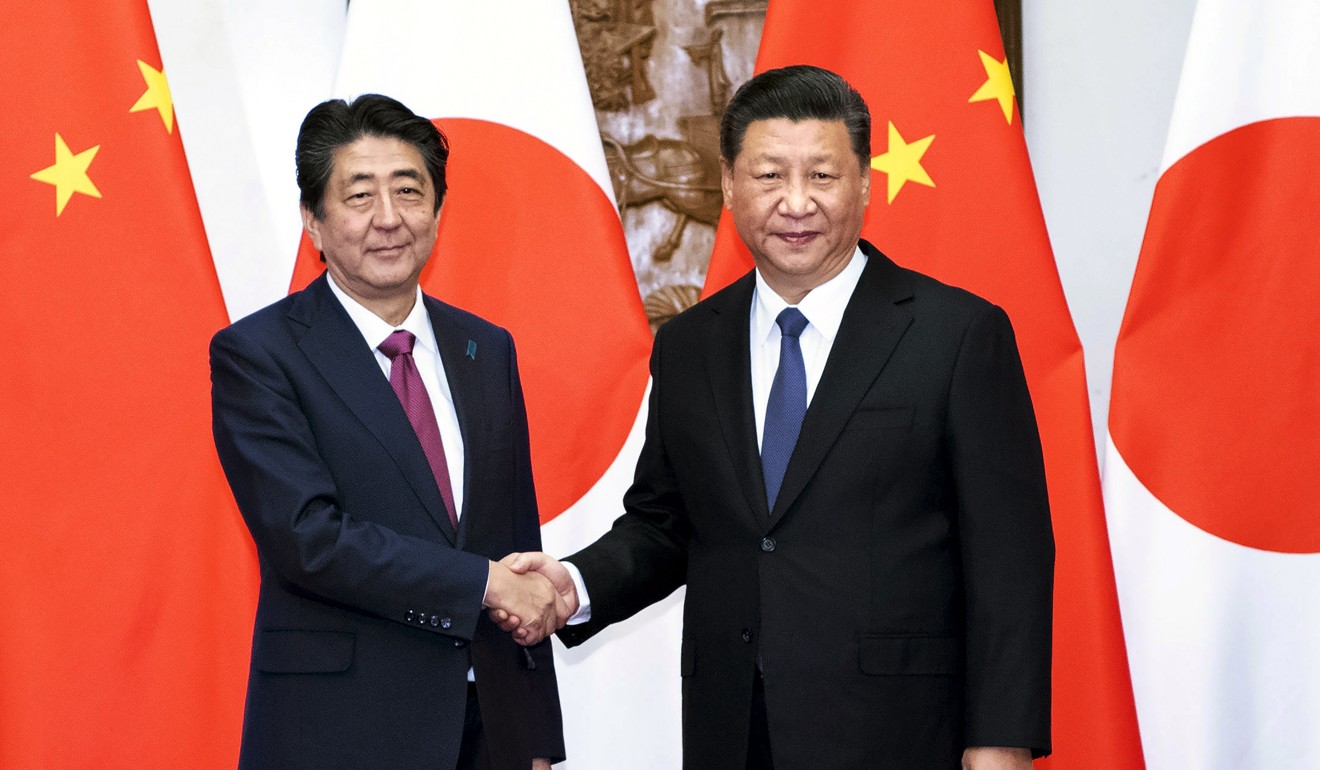

- Chinese President Xi Jinping and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, having both consolidated their positions, are the right people to put the issue to bed

Since then, this issue has remained shelved, but it has occasionally flared up, threatening to upend Sino-Japanese relations. In these four decades, no generation has proved any wiser.

If Abe and Xi are serious about fixing Sino-Japanese ties, then it’s time to finally settle the Diaoyu/Senkaku issue, once and for all. Keeping it shelved means just bottling up tensions until they boil over and wreck bilateral relations again. These relations will never be put on a solid footing as long as they are haunted by this dispute.

Watch: Diaoyu protests rage on in Hong Kong in 2012

To solve the Diaoyu/Senkaku issue, we must first understand its origin. This dispute isn’t about oil, gas, fish or geostrategic position. The world’s second and third largest economies didn’t jeopardise their economic ties for less than 200 million barrels of oil.

The rocks have had no practical value, but this hasn't stopped millions on both sides of the East China Sea attaching symbolic value to them

It’s easy to understand the largely irrelevant value of the islands (or, more precisely, rocks) just by looking at a few photographs.

Over the past four decades, the rocks have had no practical value, but this hasn’t stopped millions on both sides of the East China Sea attaching symbolic value to them.

To the Chinese, the Diaoyu Islands are the first piece of Chinese territory that Japan conquered in 1895 and the only piece that still remains under Japanese sovereignty. To the Japanese, the Senkaku Islands are the first piece of Japanese territory that a rising China has tried to take over, aiming to establish its superiority over its smaller neighbour.

Even if, one day, Beijing and Tokyo could agree to share the resources around the rocks, the problem will not go away. For hundred of millions in both countries, the wound would still be open and the dispute still be alive.

But there is one way to solve this dispute: joint sovereignty. This idea isn't new – condominia have historically existed throughout the world, with the Pheasant Island, shared by France and Spain, a successful example for over three centuries.

It isn’t even a new idea regarding the Diaoyu/Senkaku dispute: Akikazu Hashimoto, Michael O'Hanlon and Wu Xinbo have proposed such an approach, though a more limited one, in 2014. Unfortunately, even this limited proposal wasn’t taken up by the two governments.

Because the Diaoyu/Senkaku rocks are uninhabited, joint sovereignty is truly possible

Yet, this is the only real solution to the dispute. Because the Diaoyu/Senkaku rocks are uninhabited, joint sovereignty is truly possible. If these were inhabited islands, it wouldn't have worked: which laws would have applied? In what court would offenders have been tried?

The two governments could agree to share sovereignty over the rocks, which would forever remain as they are today: uninhabited and under restricted access for both Japanese and Chinese citizens. The rocks would generate their 12-nautical mile territorial sea and wouldn’t have any other influence over the maritime delimitation of the East China Sea.

Both countries could continue their patrols, but coordinating them, instead of competing to prove that one side has a stronger claim. Or they could follow the Franco-Spanish example: six months of Japanese administration, six months of Chinese administration.

Most importantly, the Diaoyu/Senkaku rocks would be known by both names (or as Pinnacle Islands) and, on every map, would be indicated by a circle in two colours: a semicircle with Japan’s colour and a semicircle with China’s colour.

The central idea is that both countries would have sovereignty over these uninhabited rocks. They would no longer be Chinese or Japanese, but Chinese and Japanese. This solution might not satisfy all the people in both countries, as some would prefer unilateral sovereignty and administration.

Yet, short of war, ownership by a single country is no longer possible. The best solution for China and Japan is to share sovereignty over the rocks and move on from this issue that has haunted their relations for long enough.

Both Abe and Xi have now established their power and their nationalist credentials. It’s doubtful that Japan and China will simultaneously have other such strong leaders soon. If any two leaders could solve this issue, it’s them.

The generation of politicians of the 1970s was wise enough the leave the Diaoyu/Senkaku issue aside, but unfortunately, not wise enough to solve it.

If Abe and Xi really want to strengthen bilateral relations and leave their mark on history, then they should prove that they are wise enough to share these small rocks, with so much patriotic fervour attached to them. It’s now or never.

Andrei Lungu is president of The Romanian Institute for the Study of the Asia-Pacific (RISAP)