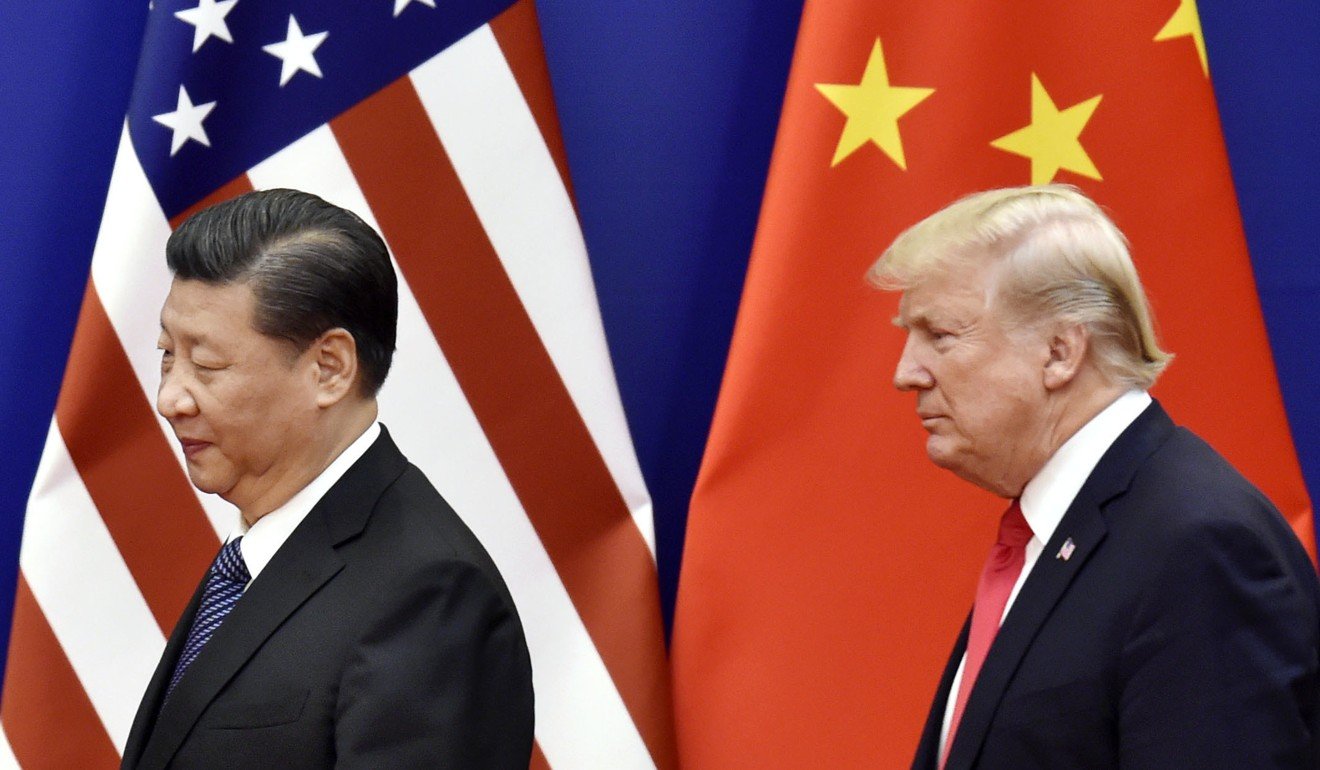

Escalating the US trade war is not in China’s interest. Reform is what it must do

Andy Xie says China could easily absorb the tariffs the US has proposed so far, but may face disaster if the conflict escalates. The best course of action for Beijing would be to use the opportunity to enact the economic reforms it must carry out eventually

China’s successful development is a result of continuous reform and opening up, hard work and patience, not confrontation or expedience. Even if the US tariffs stick, China’s economy can easily absorb them.

The trade dispute between China and the US is threatening to get out of control. It could lead to a collapse in confidence that could trigger a global financial crisis. The Trump administration is unlikely to change its behaviour because it subscribes to the madman theory in foreign relations and is not sophisticated enough to understand the chain reaction from a confidence crisis.

Only China’s restraint could calm the markets and avoid a crisis.

Trade war: China to retaliate after US proposes fresh tariffs

The economic significance of the tariffs has been hugely exaggerated: 25 per cent on US$34 billion is an extra US$8.5 billion. China’s exports are likely to top US$2.4 trillion in 2018. The tariff impact is therefore symbolic. Even the 10 per cent tariff on US$200 billion only amounts to an additional US$20 billion. The numbers are not big, in relative terms.

The tariffs shouldn’t significantly affect China’s competitiveness. China’s labour cost is less than one-fifth of the OECD level. Adding 10 or 25 per cent to it won’t affect China’s competitive position relative to the US or other developed economies. While some production could relocate to other emerging economies, they just don’t have the scale to take over significant value chains from China.

China’s exports have been subject to more anti-dumping measures – far more serious trade barriers than normal tariffs – than the rest of the world combined. And, yet, China’s exports have risen 12-fold in the past two decades. Scale and speed have conferred such a huge advantage to China’s competitiveness that trade barriers in any one market don’t slow it down meaningfully.

Watch: The trade war and its impact on consumers

China should see the trade tensions as a sign that its current economic structure needs to be reformed to fit better into the world. China has grown rapidly for four decades. Its peculiarities haven’t bothered the world because its impact was small. Now it is the second-largest economy, its peculiar features are exerting macro influences on the world.

China must get ready for the next battle on the exchange rate front, a much more serious proposition than the imposition of tariffs. The Japanese yen tripled in value against the US dollar during its four decades of economic development. China’s exchange rate has appreciated minimally in the same time frame.

That is the main reason China’s economic peculiarities have not slowed it down. China differs from other large economies in the extent of government interference in the market. Its inefficiency is accommodated by low exchange rates. If the renminbi were to double in value, China’s economy couldn’t grow without major restructuring.

If China doesn’t reform, it is only a matter of time before an alliance of major economies forces Beijing to double the value of the yuan. Waiting until that moment is not in China’s interest.

If others complain that China’s industrial policy contains excessive government subsidies, why not scale them back and rely more on the market to create business and advance innovation? What have the subsidies done for the economy so far? After pouring in tens of billions of dollars, has China produced one significant innovation? The chances are that the market can do better.

It has become fashionable to attribute China’s success to its peculiarities. Government leadership in infrastructure development has been key to China’s success. Other developing economies should learn that.

Misinterpreting China’s success could lead to serious mistakes. China should learn from Japan’s experience. It believed for a time that it had found a better model. The reality was that its exchange rate was undervalued. After the yen was brought up to the OECD level, it has stagnated ever since. China should not repeat the mistake.

Andy Xie is an independent economist