Advertisement

Opinion | Behind the US-China trade war lies a competition for dominance and a rising tide of protectionism

Lawrence J. Lau says the competition between the world’s two largest economies doesn’t have to be a zero-sum game, while isolationist sentiment, particularly in the US, can be stemmed with a redistributive tax system

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

The trade war between China and the US is actually not about trade. It is driven by two important long-term developments simultaneously in play in China-US relations. The first has to do with the potential competition between China and the US for economic and technological dominance in the world. The second has to do with the rise of populist, isolationist and protectionist sentiments in the world in general and in the US in particular.

The competition between China and the United States has been ongoing, if implicitly. It did not begin with US President Donald Trump and will not go away even after he leaves office. It has come to the fore because China’s gross domestic product shot up from only 20 per cent of the US’ GDP in 2000 to about two-thirds in 2017, and may catch up sometime in the 2030s if current trends continue.

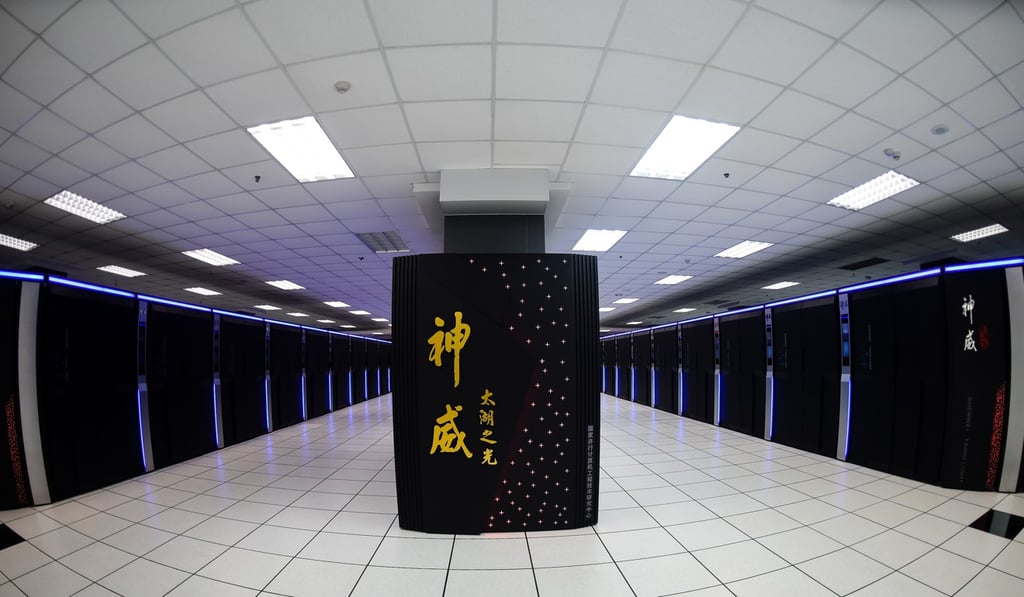

Comparison, and hence implicit competition, between the two largest economies in the world today is unavoidable. However, competition need not be destructive. For example, the competition to create the world’s fastest supercomputer has already resulted in both countries producing better, speedier computers.

Advertisement

The champion this year is the IBM Summit, an American machine that beat the Sunway TaihuLight, a Chinese computer which topped the Top500 list of supercomputers in 2016 and 2017, and which uses entirely Chinese-made chips. This is not unlike the Sputnik moment in 1957, which spurred the US to accelerated development of science and technology. The trade war, which has the potential to disrupt the supply of advanced semiconductors from the US, is likely to reinforce Chinese determination to become self-sufficient in them.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x