Macroscope | The US deficit is much larger than official estimates – if hidden costs are taken into account

Daniel Blitz and Robert Dugger say upgrading the country’s infrastructure and transitioning to clean-energy systems are upcoming expenditures that are not accounted for in the US’ calculations of its deficit

Former US Treasury Secretary Lawrence H. Summers recently quipped: “Fiscal stimulus is like a drug with tolerance effects; to keep growth constant, deficits have to keep getting larger.”

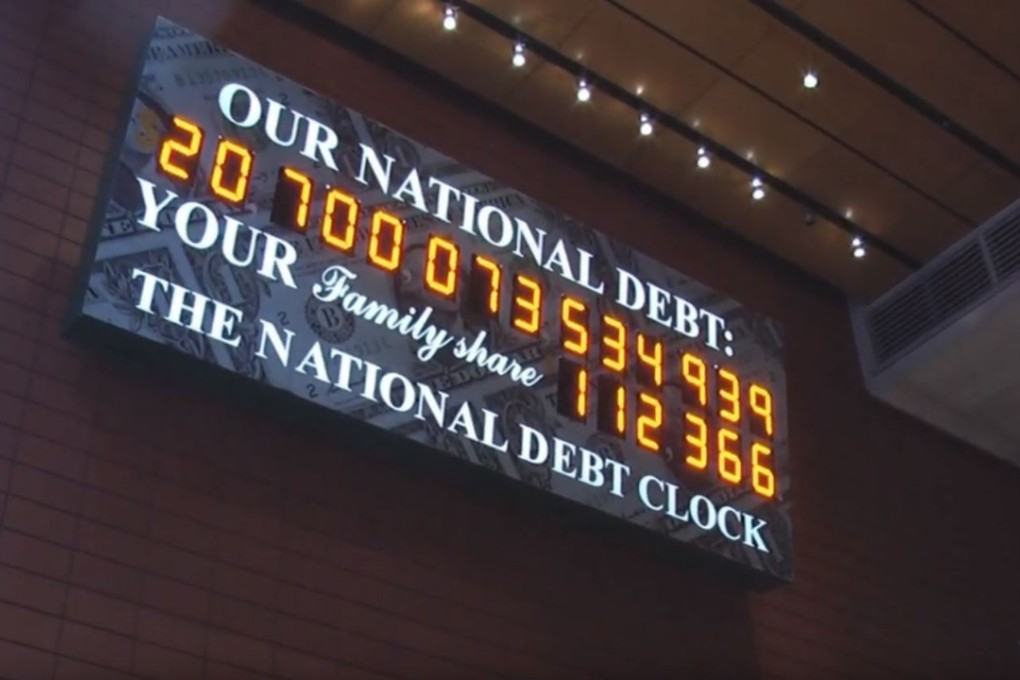

People like Summers worry about deficits because they doubt that the money the government is borrowing is being spent in ways that will push the long-term growth of gross domestic product above that of the debt. Unless the mix of spending changes, the debt-to-GDP ratio will continue to grow, foretelling disaster.

Others do not share such concerns. On the political left, Nobel laureate Paul Krugman, for example, argues that for “a country that looks like the United States, a debt crisis is fundamentally not possible.” On the right, John Tamny, a Forbes contributor, says, “Ignore the endless talk of doom, budget deficits really don’t matter.”

But while judgments differ about the sustainability of US government debt, they both accept the standard measure of it as accurate. This is a mistake, and possibly a catastrophic one.