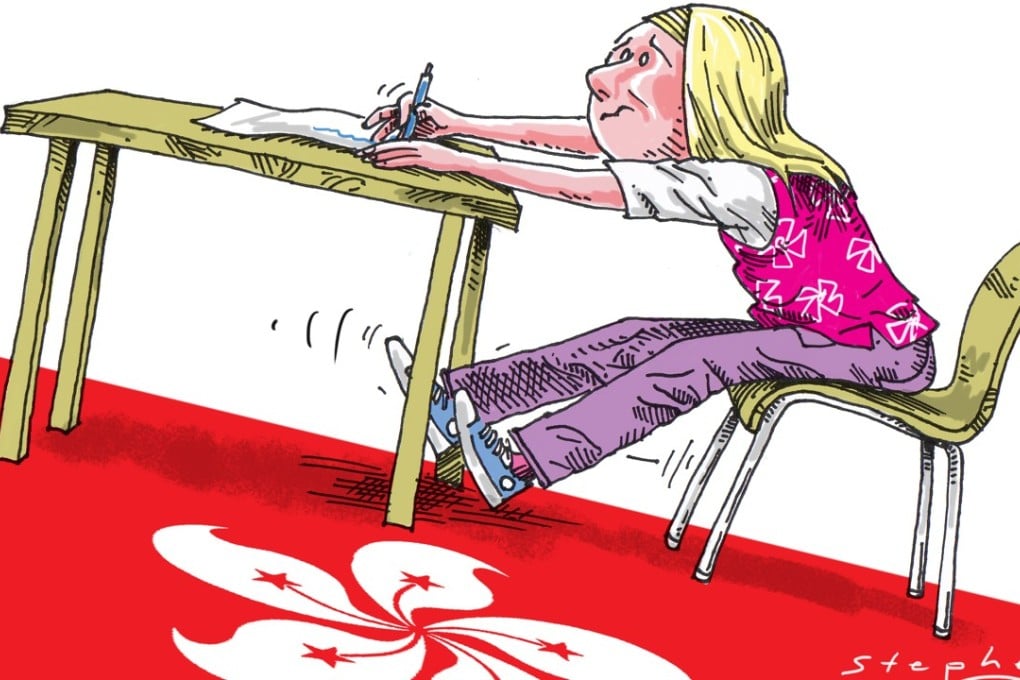

Opinion | Culture shock: the upside-down world of white families navigating Hong Kong’s local school system

Julian Groves says as a growing number of Western expats place their children in government-funded Chinese medium of instruction schools, they come up against similar challenges to those South Asians face in a system unprepared for their presence

“Do you realise this is a Chinese school?” the deeply-concerned head teacher told an American mother of two primary school-aged children after she handed in an application for her children to study at her local Chinese medium of instruction (CMI) government school last year.

This mother is one of a growing number of parents who either grew up in Hong Kong or have settled here for work from the West, and seek to put their children through the local education system rather than the private English medium of instruction (EMI) international schools.

Aside from having to persuade teachers at the better schools to admit their children, many of the parents we interviewed reported that their children experienced problems in the schools to which they were admitted. An architect from Italy, the mother of two daughters, told us that the teachers at her local Chinese primary school held little expectation that her eight-year-old would handle the language requirements. Consequently, her teacher put her daughter on separate tables with other English-speaking children and gave her less-rigorous assessments.