Advertisement

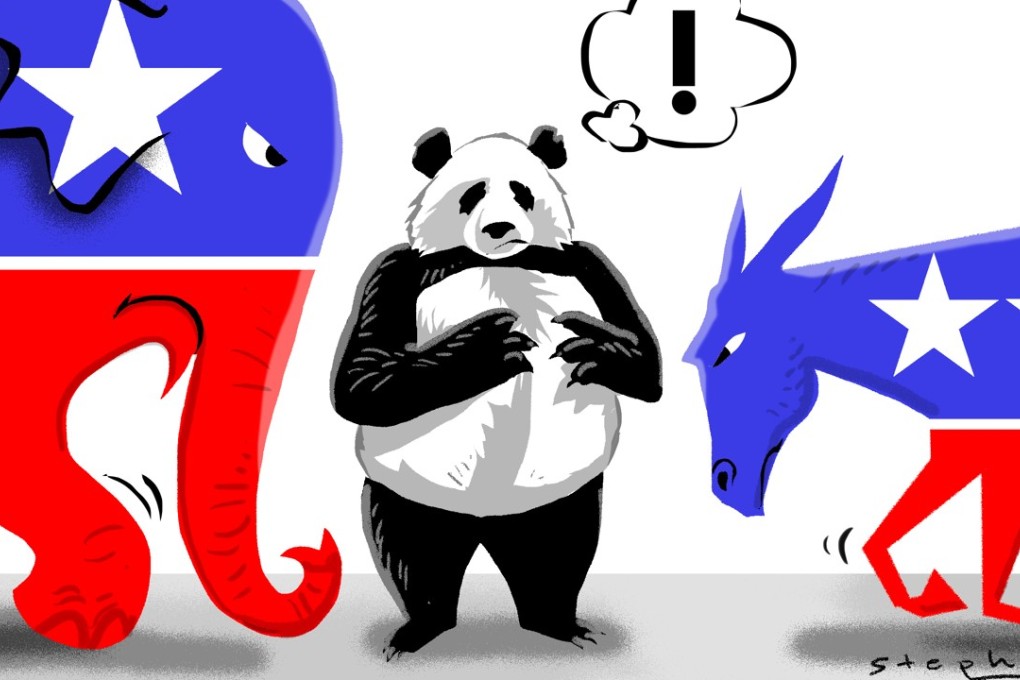

After the US midterm elections, don’t count on a Democratic Congress to soften Trump’s hard line on China

- David Shambaugh says a confrontational bipartisan consensus towards China has taken shape, as antipathy grows across different sectors of US society

- Until Beijing changes its repressive and aggressive policies and actions, the new American hard line can be expected to endure

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

With the all-important US midterm elections nearing, and the prospect that Democrats will take control of the House and possibly the Senate, many are wondering if such a change would herald any substantive change in the Trump administration’s or American policy towards China.

It is very unlikely that the election outcome will appreciably change the hardline China policy. The reason is because there now exists a quite strong bipartisan consensus for pursuing a toughened China policy.

Not only have Democrats and Republicans in Congress found consensus on the underlying rationale and elements of a hardened China policy, but it spans various professional sectors across the country.

Advertisement

If anything, if the Democrats take control of Congress (or even one house) the policy is likely to become ever tougher – as Democrats will push the Trump administration to be much more critical of China’s human rights abuses and increased repression.

They may well find a willing administration, as Vice-President Mike Pence’s recent speech on China contained numerous criticisms of human rights transgressions.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x