Opinion | America can falter, but the Western liberal order it helped to build must not

- Kori Schake says Trump’s unilateralism and disdain for values-based policymaking should push America’s allies to step up in defence of the global order, now under attack from the authoritarian alternatives promoted by China and Russia

The liberal order was not created by starry-eyed idealists in faculty lounges. It was hewed by the hard men who defeated Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan and dug the world out of starvation and rubble in its aftermath. They built it because they lived the wreckage of tens of millions of lives destroyed by an unregulated international system where threats gathered, strong states preyed on the weak, tariffs strangled trade, central bank policies exaggerated economic hardship, and aggression mounted until even strong states feared being overwhelmed.

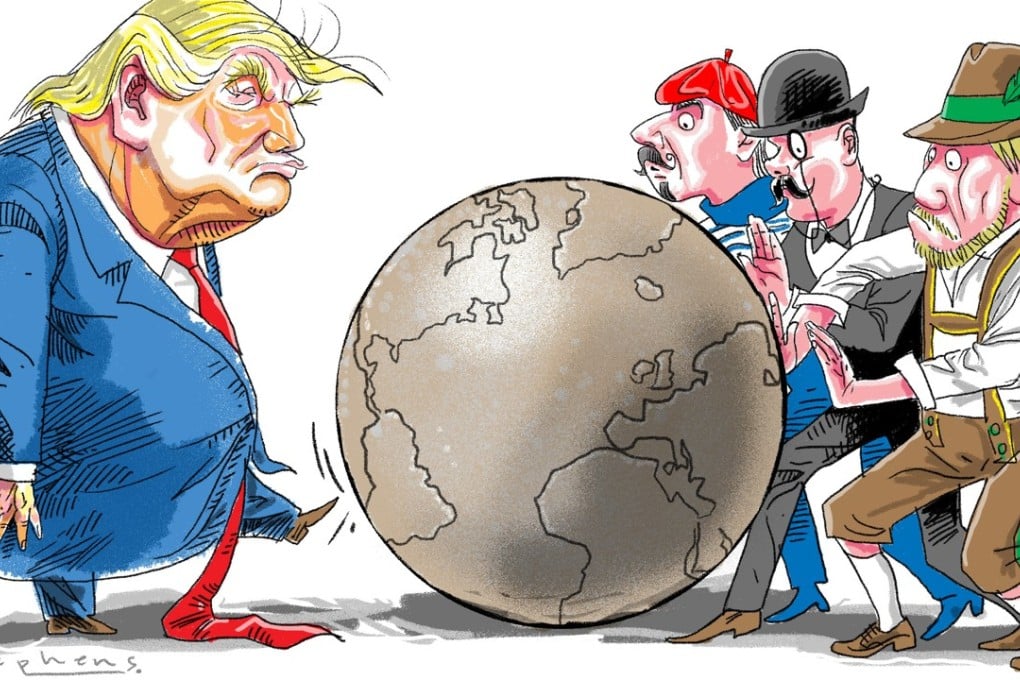

But the current president of the United States seems not to believe in the fundamental building blocks of the existing order, nor accept that they benefit the US nearly enough to justify their perpetuation. Trump considers the existing order a conspiracy: “allies” free-ride off US military power while taking advantage of trading arrangements that disadvantage America. His vengeful unilateralism has injected an unwelcome instability within the Western camp.

America’s allies are the most strident voices about preserving the existing order, and are talking tough about preserving it despite US opposition. French President Emmanuel Macron tweeted after the G7 meeting that “the American president may not mind being isolated, but neither do we mind signing a six-country agreement if need be”.

Because these countries represent values, they represent an economic market which has the weight of history behind it. America’s allies are the world’s strongest economies, most stable democracies, and most institutionally protected countries in the international order. They have the most to lose if the order erodes, but they are also the countries most able to preserve their interests as the international order transforms.