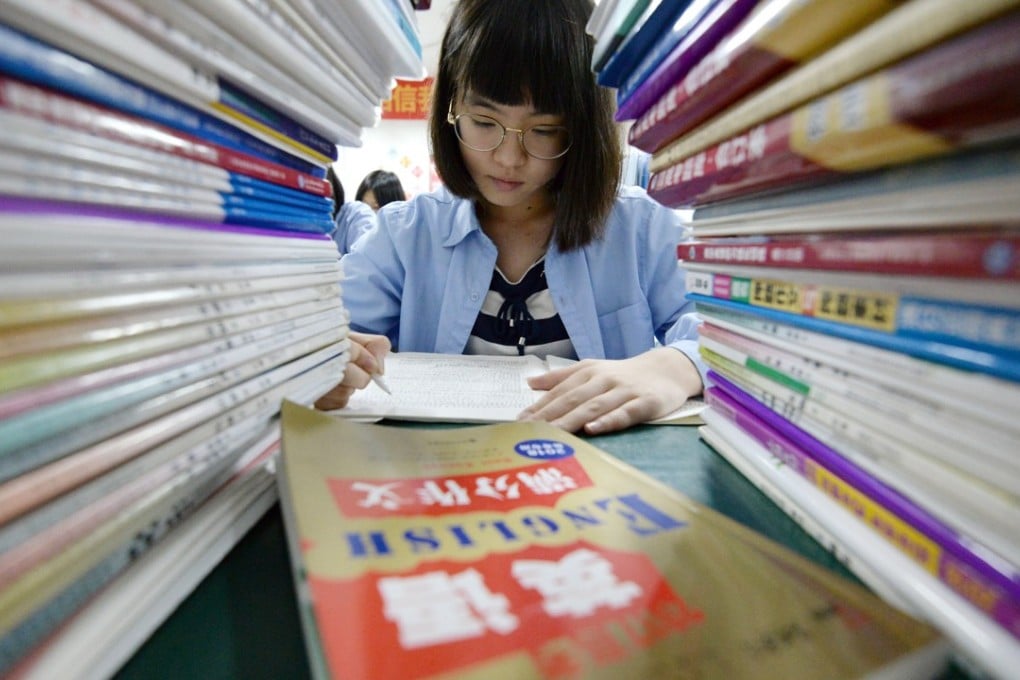

Opinion | How English testing is failing Chinese students by driving numbers, not proficiency

- Philip Yeung says as the market for English assessments, such as IELTS, grows in China, test designers should ensure that exam questions encourage true language learning

If any “English as a second language” test has an oversized footprint in China, it is the International English Language Testing System (IELTS). With Donald Trump threatening to shut Chinese students out of US universities and colleges, it will grow even bigger, for the simple reason that it is the one test that is widely accepted in Canada, the UK, Australia and New Zealand for higher education purposes – the spillover countries for America’s rejects.

How big is IELTS? Last year, it had over 3 million test takers, with Chinese students accounting for over half a million. If any country typifies an exam-driven country, it is China. It is made for IELTS.

With only 27 per cent of Chinese candidates scoring the benchmark 6.5 or above for admission to overseas universities, the retest market is massive. Often, the same candidate attempts the test multiple times. At 2,020 yuan (HK$2,288) per test, it is a gold mine for the testing authority, in this case the British Council.

But as IELTS has continued to grow, there have been rumblings of complaint from educators that the test is anti-educational. First, some academics have cast doubt on its value as a predictor of tertiary English-language proficiency. Eight British universities have recently had to denounce rumours that they are rejecting Chinese students, but some Chinese suspect there is a kernel of truth there; some universities consider their Chinese students linguistically unprepared for academic studies.

Students in China, for their part, accuse IELTS of making the exam questions so tough that they are forced to resort to playing guessing games. Instructors often give up teaching comprehension and instead teach exam skills that help students narrow down the answers to multiple choice questions.