US-China cold war’s paranoid nationalism is spilling onto university campuses, hurting Chinese students

- Tom Plate says Chinese students’ opportunity to learn from and with their US counterparts at universities has been disrupted by nationalist demands from both governments

One has to wonder about FBI officials when they agree with the Trump administration. Are they clear what they are saying? Collecting information is precisely what “scholars” and “researchers” do at universities. Sometimes they even share it – and/or publish it! – and hope it gets widely circulated. A relatively tiny amount is classified or sensitive – and unavailable to the average Chinese sophomore from Xian. Besides, there’s not enough good top secret stuff to occupy 300,000 students.

Even so, the loyalty temperature-taking on our campuses regarding China and the US does appear to be heating up, and on both sides of the divide. As a university professor, I loathe such displays, especially on campuses, and wish paranoid FBI officials would pop chill pills and maybe even go back to school to learn about true intellectual life, as well as the culture of scholarship and information-sharing.

And, for that matter, I would ask China’s Ministry of State Security, if it does require some of its student exports to live a double life, to cut it out before the FBI has something to sink its teeth into.

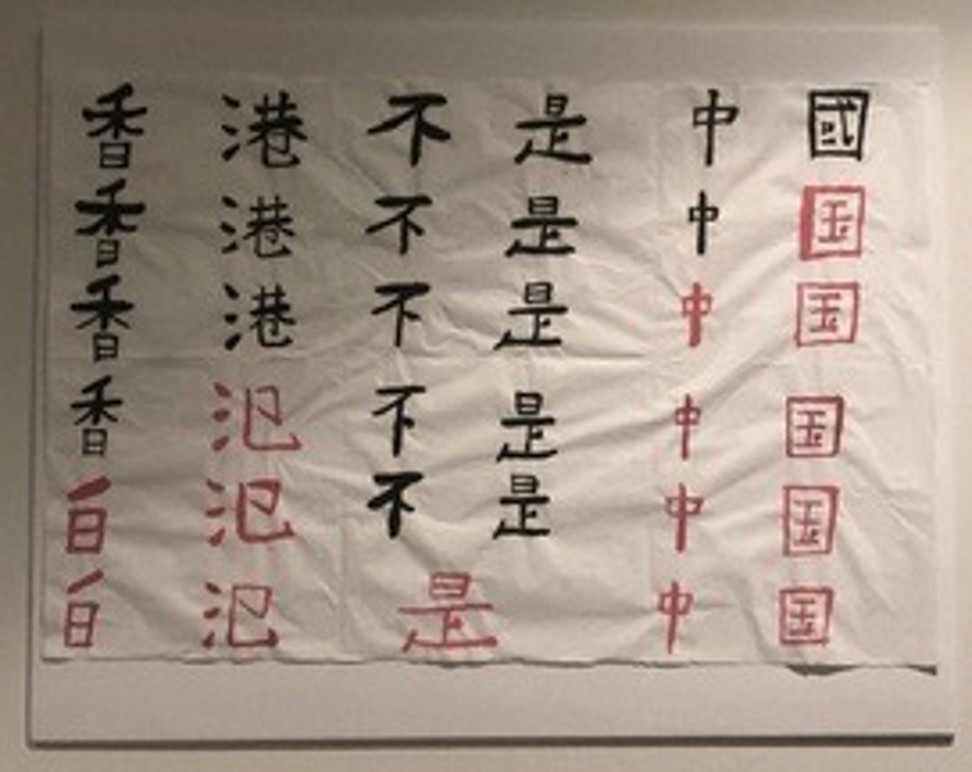

The young man was to create a poster illustrating the difference between traditional and simplified Chinese characters. Having done so, he then posted it, with the instructor’s OK, in a section of the university library designated for the display of student work.

Imagine! A few dozen Chinese mainland students got riled up and viewed the poster as advocacy of independence and complained to university authorities that they found the work needlessly provocative.

The university, reacting with both calm tenderness and unmistakable clarity, reiterated its free speech policy while noting the oft-bumptious nature of university culture. Even so, the student, shaken up by the fuss (and well-aware of how high-strung students can get, especially around final exam time), had the poster taken down.

This incident illustrates, in these absurdly fraught times, how even when no one does anything wrong, things seem to go wrong anyway. The calligraphy instructor had given out a perfectly good assignment. The student responded with what he thought was a good product. The library posted it for all to admire. The university administration promptly and correctly defended the faculty member – and the student – when challenged for an explanation by any and all.

China has 325,000 chances to win over America. Why not use them?

So, were the Chinese students from the mainland wrong to launch their objections? No. By so doing, they brought attention to the salience and complexity of the continuing conundrum of Hong Kong under the “one country, two systems” mantra.

They also reminded us that students from other lands do not place their cultures and emotional loyalties into some sealed bag at customs when they reach our shores. And they reminded us that, as much as they appreciate America and its zany ways (and most really do), they are not Americans; they are Chinese.

Is it imaginable that at least some of the mainland student complainers had the thought that if they did not raise the China-sovereignty-sensitivity flag, authorities back home might make note on their return.

China and the US, 40 years on: it’s complicated, but they’re still talking

Columnist Tom Plate is the author of “In the Middle of China’s Future” and “Yo-Yo Diplomacy”. He teaches at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, where he is clinical professor in the Asian and Asian-American Studies Department