China has no use for democracy. It needs a strong leader like Xi Jinping right now

- Chi Wang says China has no ideological basis for the development of a system that prizes personal freedom, nor any history with the rule of law

- The reality is, for the People’s Republic, strong leadership makes better sense

Optimists can argue instead that Trump’s degradation of democratic norms will lead Americans to appreciate and hold on to them more dearly in his wake. It is unclear even now which outcome is more likely, but it is difficult to find the state of the nation encouraging today.

Previously, emperors in China were said to rule because of their “Mandate of Heaven”. When Mao seized power, it was clear that he had won his position through revolution. Yet the selection of Xi, like the selection of his predecessors since Mao’s death in 1976, is cloaked in secrecy.

When Xi was named vice-president in 2008 and the presumptive successor to Hu, it came as a surprise to many China watchers. Yes, Xi had a strong background in the Communist Party and held the distinction of being a “princeling”, a son of a first-generation party member. Yet there were many other senior officials with similar credentials who were arguably better positioned for leadership positions.

After 70 years of rule in the People’s Republic of China, authoritarianism has arguably only grown stronger, even as its people have become increasingly aware of alternative forms of government. The current generation in China has the opportunity for more exposure to the outside world than their parents, through the internet, social media and the lifting of many restrictions on trade, travel and student exchanges.

Does it have to be this way? Could China elect its leaders democratically like we in the US do, where even those who oppose Trump largely concede that he was elected by the people’s will?

Putting aside the question of whether China even has the institutional capacity to support a democracy, or any indications of a democratic reform mindset, at either the grass-roots or government levels, it doesn’t seem that the nation could support a democracy. China lacks the ideological framework under which democracy could spontaneously develop or be fostered. Confucianism is inherently undemocratic; it encourages obedience, not freedom or personal liberty.

Most strikingly, China lacks any history with democracy or true representative government and the rule of law. Before the establishment of the Republic of China, China was ruled for thousands of years by successive dynasties. Even the Republic of China could not be categorised as democratic, as the people had no say in choosing its leadership. Further, it did not establish definitive control over vast swathes of Chinese territory.

Instead, many areas of China descended into rule by warlords following the Qing collapse. China’s large population, stretched over a wide area separated by geological, societal and climatic boundaries, fosters a government that rules through authoritarian means, where power is taken by those with the strength to do so, not because of the people’s will.

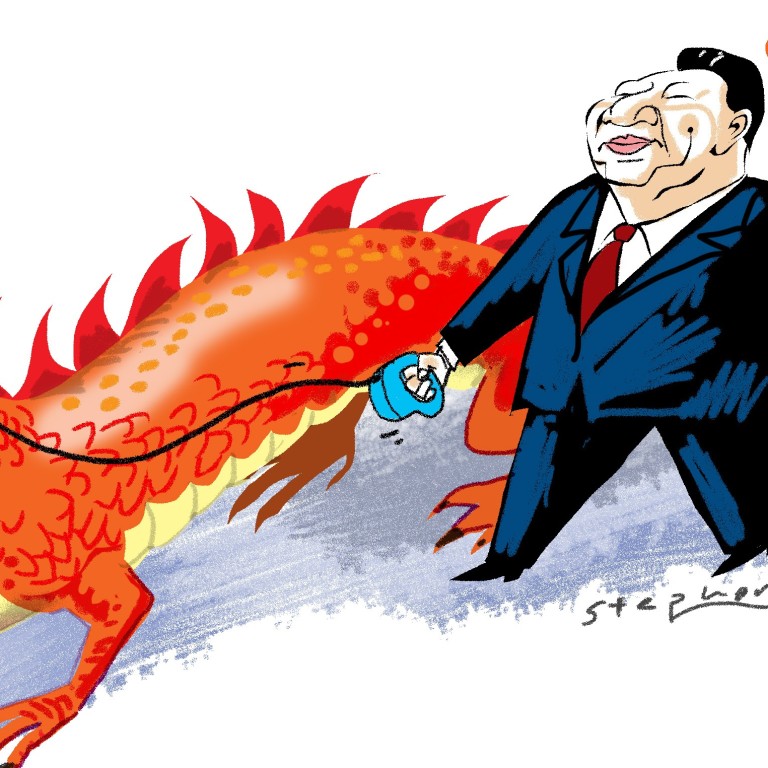

Understanding these realities of leadership in China, it becomes apparent that regardless of how Xi was selected, he is the leader that China needs right now. The crime and corruption that accompanied reform in China threatened to collapse the government in on itself. Further, with the US president leaning increasingly towards hawkish China policies, China cannot afford weak leadership.

At this critical junction, coinciding with the 70th anniversary of the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, Xi is the right person to lead China.

Chi Wang, a former head of the Chinese section of the US Library of Congress and former university librarian at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, is president of the US-China Policy Foundation