Advertisement

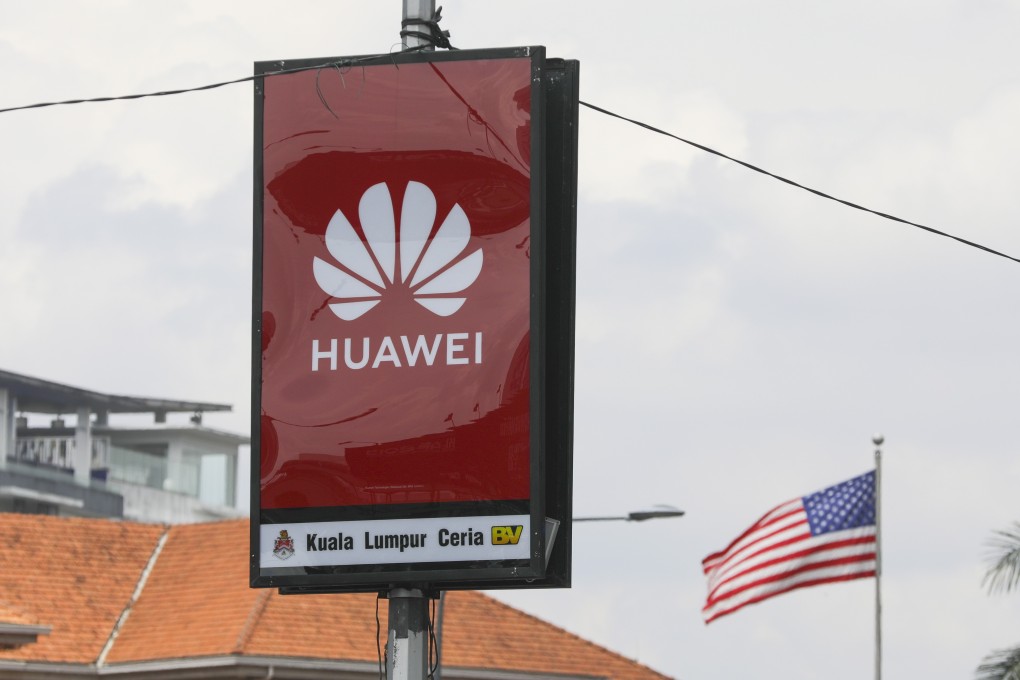

Opinion | Is the US trying to break up the internet to contain Huawei and stay ahead of China?

- With its actions against Huawei, the US is effectively threatening to segregate the internet. Chinese companies have operated at a speed and scale that threatens US dominance in tech, and Washington’s response will shape the knowledge economy

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

It is a cliché to say that we live in a digital age, with many countries upgrading to become knowledge economies. There is also supposedly a digital divide, between those who have access to technology and those who do not.

But the United States’ recent action against Huawei – under a Trump administration order, the Chinese technology giant might lose access to future versions of the Android operating system for smartphones – suggests a real divide is in the making. The internet might break up into digital networks that are perhaps firewalled against each other, amid a situation of geopolitical rivalry, technological competition and seriously different governance values.

Lest we forget, the internet was created by computer scientists for the US defence community, and individuals were allowed to develop the technology behind the information superhighway through innovations in hardware, software and data transfer. (The World Wide Web, an information retrieval system, was one such innovation.)

Advertisement

Internet stakeholders, including Google and the non-profit Internet Engineering Task Force, collectively maintain what has become the critical infrastructure for global communication and social media.

It is a complex network that does not have a single architect, but grows through the continuous tinkering by web participants and the linking up of domestic networks and, today, smartphones. The internet forms the basis for the worldwide knowledge economy, through which knowledge is created and shared.

Globalisation took a long time to take off, but essentially there are three levels of networks that facilitated the exchange of goods and services, capital and knowledge.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x