Advertisement

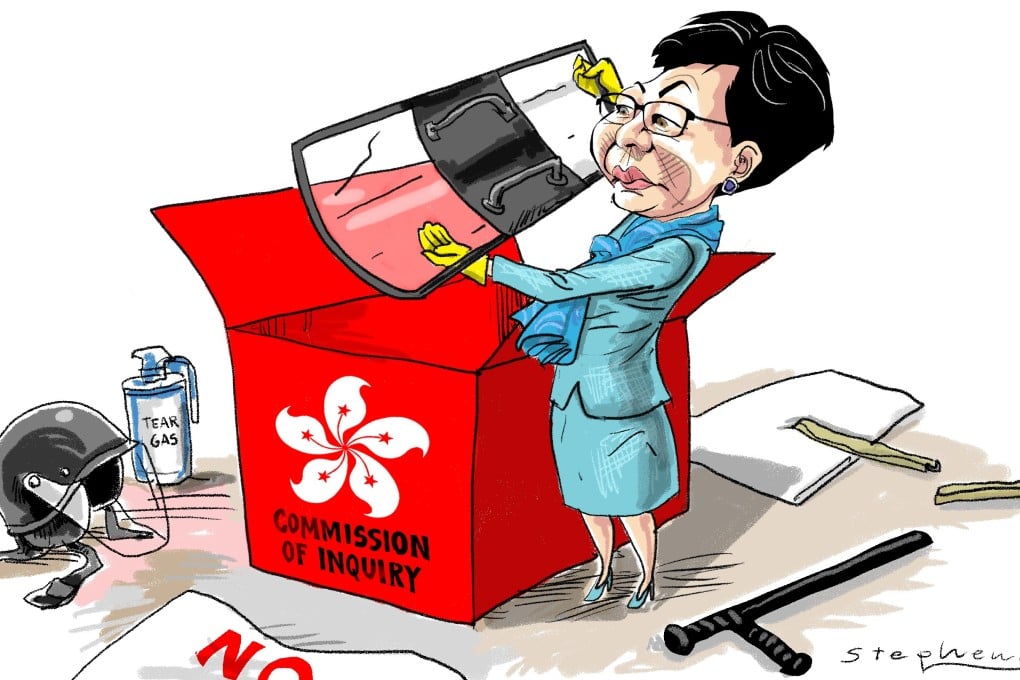

Opinion | A commission of inquiry into police conduct can help Hong Kong’s healing process – an amnesty for protesters cannot

- An open and wide-ranging inquiry, led by a judge, would be the most effective way to ascertain the truth, and the process will have a therapeutic effect on society

- Carrie Lam, meanwhile, must encourage more debate in government and speak up for Hongkongers, while all officials should remember they are servants of the public

4-MIN READ4-MIN

Like my fellow citizens, I am greatly concerned by recent events arising from the controversy over the fugitive offenders bill. As a former chief justice, I have no wish to participate in the political arena. But, having regard to the present extraordinary situation, I wish to contribute to the discussion, especially as certain issues have a legal dimension.

Overall, there is no doubt that the government made a serious error of political judgment. They misjudged the mistrust which the people of Hong Kong have of the mainland legal system and their concern of what they perceive to be the increasing “mainlandisation” of Hong Kong.

The commitment of Hong Kong people shown by their peaceful and orderly marches was impressive. The central government also showed wise pragmatism in supporting the abandonment of the bill, even though it had majority support in the Legislative Council.

Advertisement

Unlawful and violent behaviour must be strongly condemned by all. The scenes in the storming of Legco were ugly and shocking. Under the rule of law, this cannot be tolerated. The law was wilfully disobeyed. Those responsible must be brought to justice. If convicted after a fair trial, the courts should consider deterrent sentences.

Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor has already sincerely apologised for the government’s handling of the matter. She should be given the chance to continue to serve. I respect her for her unwavering dedication to public service.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x