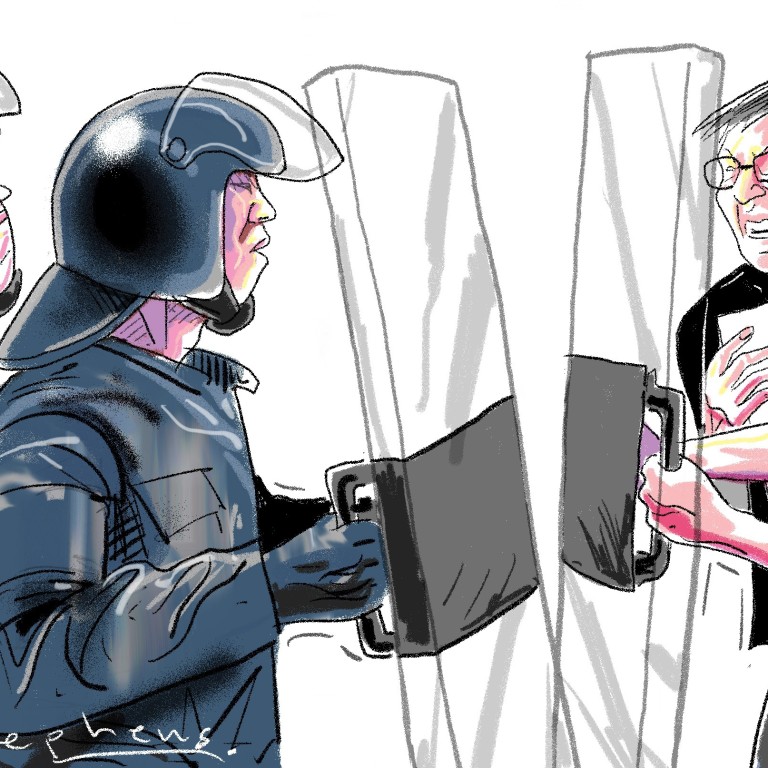

As antagonism between Hong Kong protesters and police escalates, there’s still hope for healing the rift

- While protesters must stop their inflammatory rhetoric, the police must revisit its protocol for handling mass protests, reflect on its belligerence towards protesters and use the opportunity to increase transparency

There are some protesters who engage in violence, and while their choice must be rejected as ineffective, we must ask serious questions about them beyond mere condemnation: What drove them to this? How could Hong Kong rehabilitate and reabsorb them into a political structure in which they see the promise of change? More importantly, who are we, as members of the public, to determine guilt when such tasks should be reserved for the courts and other just institutions?

The administration conflates boldness and integrity with obstinacy and inertia. Its continued refusal to address the deep roots of police-public mistrust – turning instead to continued demonisation of protesters and tokenistic condemnation of “excessive violence” – leaves the city fundamentally damaged. The refusal to establish an independent commission not only denies justice to victims of undue violence on both sides, including journalists and public servants, but also leads to further deterioration in police-public relations and squanders an opportunity to seriously reform the police force.

The only way tensions can de-escalate is if our police transforms its internal accountability mechanisms and how the force communicates with the public.

A grand dialogue might heal divided Hong Kong – if we dare hold one

More importantly, a more communicative police force is likely to be one that better addresses the needs and concerns of the public and one that is restrained by both increased publicity and transparency. The flip side is that protesters ought to set aside inflammatory rhetoric which treats the police as a public enemy. Reconciliation calls for efforts from both sides.

Installing body cameras, including greater sensitivity training focusing on civil liberties into the mandatory police curriculum, and changes to the protocol on crowd management would greatly lower the risk of violent clashes.

Above all, the administration must do more than merely voice empty words of support for the police and reprobation of its own citizens. Dividing protesters into the law-abiding and peaceful versus the illegal and riotous does little to heal wounds in society and help us move forward. The best way to stand up for the police force is not through blatantly dismissing all criticism but embracing it as a reminder of the work to be done.

We cannot move forward if we forget the past. Genuine de-escalation will not come when police and public alike feel that governmental policy does not take their interests and voices seriously. Transparency and accountability – through structural reforms and an independent commission – are necessary for Hong Kong to truly become a better city, a home once again for all.

Brian YS Wong is a Master of Philosophy student of politics (political theory) at Wolfson College, Oxford University

.png?itok=bcjjKRme&v=1692256346)