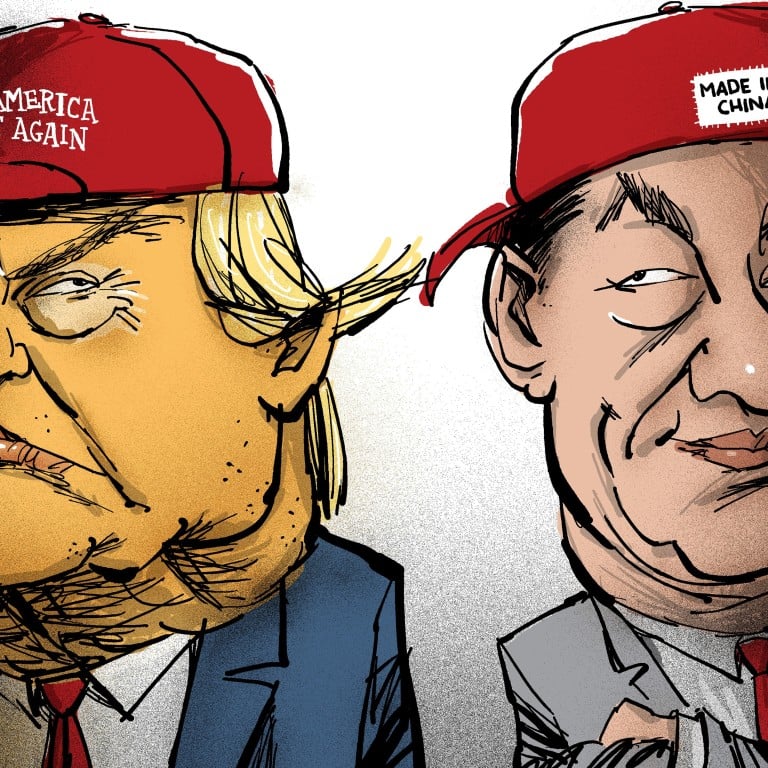

If this happens, China will have to brace itself for another decade of Trumpism and bumpy bilateral relations, in which every Chinese move is interpreted as a threat to US hegemony.

It all used to be so different. The policies and pronouncements from one US administration to the next were of little consequence to Beijing. An eight-year presidential term was a blip compared to the continuity of the

Central Committee.

But in the age of the 24/7 news cycle and

morning presidential tweets, eight years is an eternity. China no longer has the luxury of waiting for Trumpian policy to disappear. It can’t stand idly by as the US punishes

one Chinese company after another and uses arms-lengths methods to coerce other nations to follow the US’ lead.

One option is for China to reshape the world to its advantage following the US’ retreat from globalisation. It could influence multilateral organisations such as the

United Nations, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, which all shape the international rules-based order.

President Xi Jinping’s robust defence of globalisation at

Davos in 2017 was a rallying call for Chinese companies to continue their internationalisation in the prevailing framework. However, as the world sours on

globalisation, why should China be the primary defender of a system it doesn’t derive maximum benefit from?

Another option is for China to focus on its own development model. The

Belt and Road Initiative has reinforced Xi’s message that China is open for business, and setting up shop along the old Silk Road drives economic growth in China, as well as its partner countries.

Indeed, many of these partners look enviously at China’s GDP growth of

6 to 6.5 per cent per year and perceive its model as more effective than that of Western countries.

China is challenging US technological supremacy in areas from artificial intelligence to quantum computing. The

biggest players in Silicon Valley are drawing inspiration from the Chinese super-app

WeChat. The trade war has pushed Chinese companies to invest massively in tech, and resulted in Alibaba’s chip unit developing its

first core processor, Xuantie 910.

Feeling the heat, the US government has conflated its trade and national security policies by punishing Chinese companies. In May, it put Chinese tech giant

Huawei on a so-called entity list that restricts US companies from doing business with foreign firms that are considered security threats.

But, last year, Huawei alone accounted for US$11 billion in revenue going to US companies such as Qualcomm, Intel and Micron. As one quote supposed attributed to Lenin goes, “The capitalists will sell us the rope with which to hang them.”

While the trade war hurts China, there is little prospect of it destroying the world’s second-largest economy. In fact, China may be justified in believing it is strong enough not only to survive the decoupling, but to make a roaring success of it.

The question remains: to what extent will China seek to decouple from the

global framework it has endorsed since Deng inaugurated an economic policy of opening up?

The decoupling could be hard or soft. For China, a soft decoupling would mean developing its own ecosystem while continuing to engage with existing organisations and actors in the West. This would allow China to bide its time until the US embraced globalisation again and adopted a less confrontational approach to the Middle Kingdom.

A hard decoupling would be more radical. It would involves shunning the multilateral institutions, pursuing an agenda of self-interest and, on some level, reviving the kind of cold war rivalry in which two countries developed incompatible systems.

Proponents of a hard decoupling will point to the Soviet Union of the 1960s, when the country was superior to the United States until

Apollo 11 was sent to the moon. If the Soviet Union could achieve this in the 1960s why not China in the 2020s?

For the moment, a hard decoupling seems to be off the table for China. But things can change. If Chinese companies are systematically excluded from the world’s most important markets, if

Chinese students are not welcome in the US, if China loses competitiveness, then all options will be put on the table.

History tells us that when it comes to making difficult decisions, China is not short on resolve. Perhaps Western countries should think more carefully about adopting policies that force China to make decisions of far greater and irreparable consequence.

Cédomir Nestorovic is professor of international marketing and geopolitics at ESSEC Business School