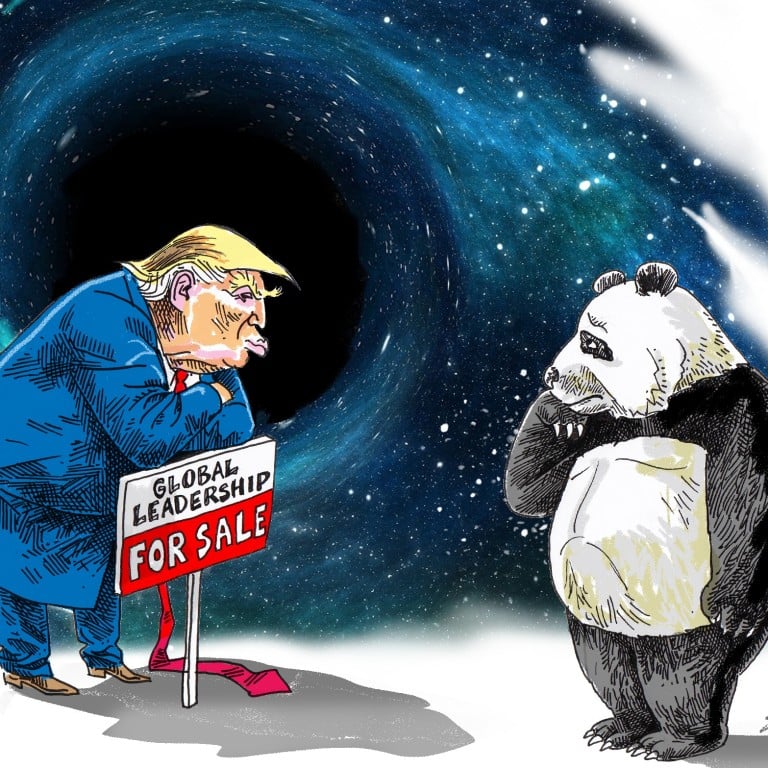

On the surface, it looks like China is ready to step into the void created by an isolationist Washington, but is Beijing really up to the task? The burdens are already mounting on China both politically and economically, making any attempt at global leadership less likely.

Take China’s lending spree, for example. The promise of

US$1 trillion makes for great soft power projection across much of the developing world. There are port and rail projects in Africa, the Middle East, South and Southeast Asia, and even Europe.

Two years into a development programme to rival any other in more than half a century and the easy money is already coming to an end. Loan defaults are

piling up. An overseas backlash is brewing over the alleged importing of Chinese workers for massive construction projects rather than using domestic labour.

And other countries now see the effects of Beijing’s political influence campaigns focused on their domestic politics. The Wall Street Journal’s revelatory reporting on the Chinese government use of Huawei to help Zambia and Uganda spy on their political opponents will only raise more concerns of meddling.

The new China development “model” barely got off the ground before being grounded. Beijing is learning a

hard lesson about ignoring loan-to-gross-domestic-product ratios that can lead to some knotty financing problems.

For years, Beijing decried the unfair lending practices and onerous restrictions imposed by the International Monetary Fund and World Bank. It

turns out that global financing standards, even when developed by “Western” institutions, are not easily avoided.

Already, Chinese officials are talking about tighter lending restrictions and a more cautious approach to new projects. Countries that may have believed in a new China model for economic growth will be disappointed with new lending terms that look increasingly like the old.

China’s massive infrastructure funding programme in Pakistan is a case in point. With US$19 billion out of US$62 billion

used or in use, Islamabad already had to negotiate a US$6 billion

bailout package from the IMF in May. . The IMF forecasts Pakistan's real GDP to drop to 2.4 per cent in the 2019/2020 fiscal year, down from an estimated 5.5 per cent in 2017/2018. With that kind of weak activity, additional loans will almost certainly need restructuring.

Defaults are piling up elsewhere, from Kenya to Venezuela and Sri Lanka, with some countries rescheduling their debt or losing their collateral. In Colombo’s case, that meant

giving up the strategically well-positioned Hambantota port that bridges South and Southeast Asia with the Middle East.

China’s economy is also

slowing as domestic debt rises and defaults loom. The days of unbridled lending will come to an end well before China spends US$1 trillion in belt and road money to claim the mantle of lender of first resort.

Following a well-worn historical path, China’s growing commercial interests around the world are also being followed by an increased global military presence. At the urging of Trump, Beijing

may start protecting Chinese ships transiting the Straits of Hormuz, a critical energy shipment choke point and site of

multiple Iranian seizures of tankers.

China also has potential naval access to ports in

Cambodia,

Pakistan,

Sri Lanka and

Djibouti, with more expected. Last month, leaders from 50 African nations met in Beijing for the first

China-Africa Peace and Security Forum, where China pledged to fund their military training. That same month, Wang Yi, China’s foreign minister, signed a defence and military cooperation agreement with the United Arab Emirates at an economic forum.

With global expansion comes a global

bill. Funding a worldwide military force does not come cheap. While estimates vary, the US continues to outspend China by at least two to three times. The US was able to fund forever wars and military expansion through massive federal

debt spending.

That was possible because the US dollar dominated global financial markets. China’s tightly

managed currency does not enjoy that kind of global access or appeal. While government bonds have

opened up to foreign investors,

concerns over currency restrictions and transparency continue to linger.

That China has not had to do much to displace the US in regional and international affairs should come as no surprise. Trump’s retreat from global leadership is a self-inflicted wound. But even with this wide opening to increase China’s global influence, Beijing will remain limited by its weakening domestic economy and a more sceptical world abroad.

Brian P. Klein, a former US diplomat, is the founder and CEO of Decision Analytics, a strategic advisory and political risk firm based in New York City