Advertisement

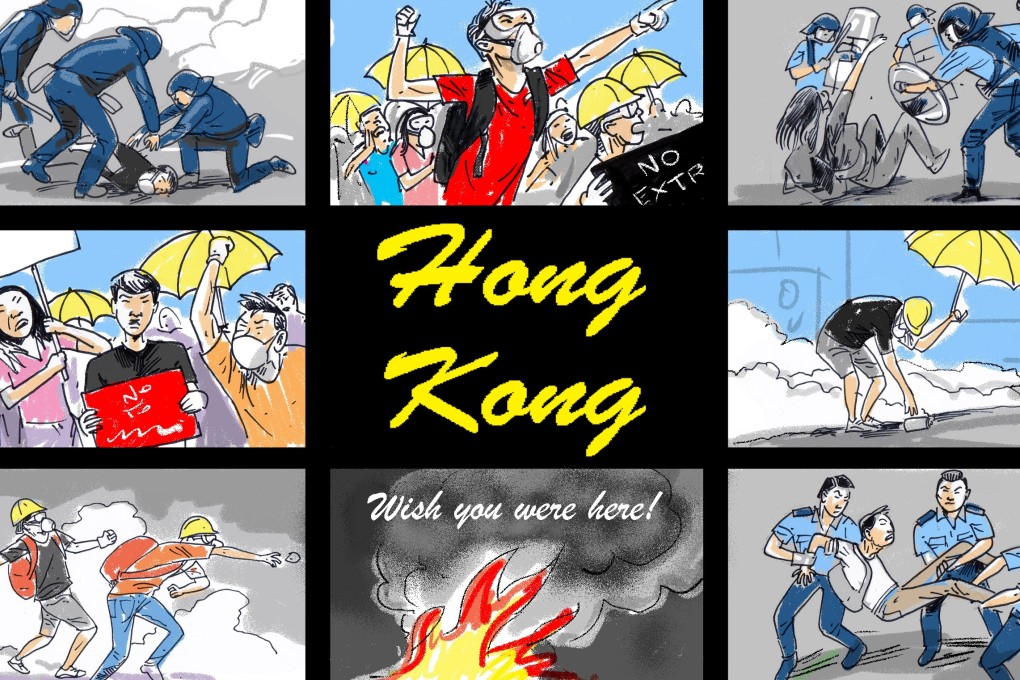

A PR campaign is not what Hong Kong needs. Carrie Lam should try solving the city’s social problems

- Hong Kong’s reputation has taken a knock, as has China’s in the West. To counter this, the government should go beyond cosmetic solutions to address people’s aspirations and the real causes of their angst

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

At a closed-door meeting with a group of businesspeople in late August, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor admitted that the city’s Information Services Department had requested proposals to “relaunch the Hong Kong brand” from eight global public relations companies. To date, it has received none.

In a press briefing on September 17, Lam indicated that “the time will come for us to launch a major campaign to restore some of the damage done to Hong Kong’s reputation”. Yes, but a PR campaign is the last thing Lam should be worrying about now.

Why did the invited global PR firms turn down this potentially lucrative assignment? In fact, four immediately declined because, in Lam’s own words, it “would be a detriment to their reputation to support the Hong Kong [Special Administrative Region] government now”.

Advertisement

It is understandable that no PR firm of international repute would want to be seen as aiding and abetting a government increasingly seen, outside China, as utterly out of touch with its people’s needs and a “white glove” for the Chinese government.

I also think that the risk of being on the wrong side of a potential Tiananmen-style crackdown could be unbearable. In addition, representing the Hong Kong government might well require registration under the US Foreign Agents Registration Act.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x