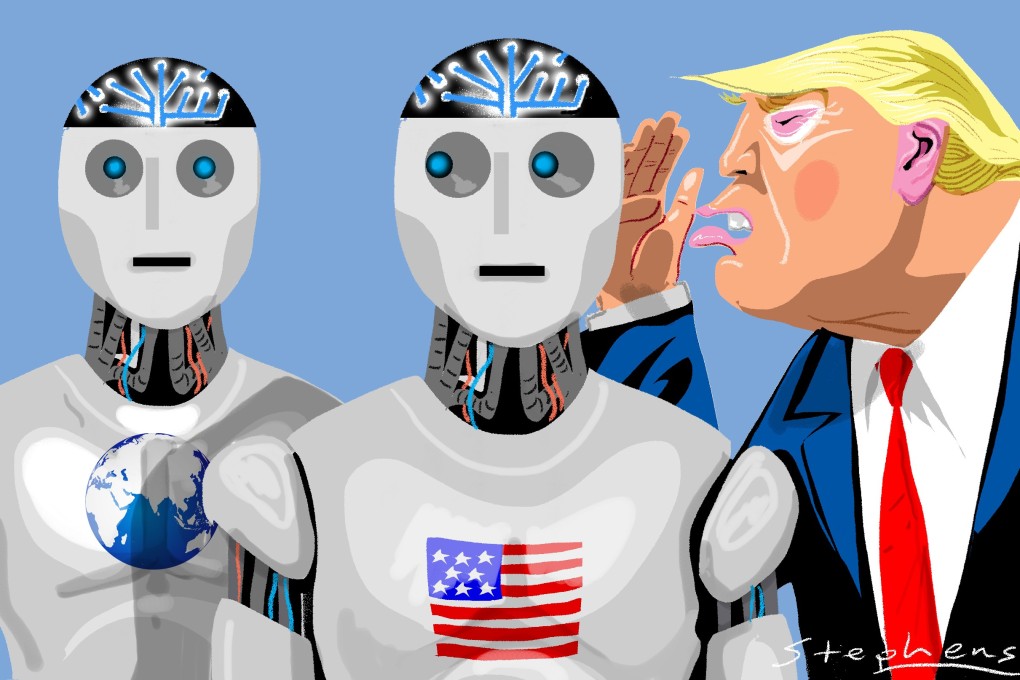

The Trump administration’s approach to artificial intelligence is not that smart: it’s about cooperation, not domination

- The US rightly sees AI as crucial for building a better world, and is making plans for regulating and developing it

- However, it is discouraging cooperation and foreign involvement when it should be fostering international standards

These officials understand that AI systems could improve welfare, increase productivity and help solve complex problems such as global warming. But countries won’t be able to reap the benefits of AI unless they work internationally, as well as domestically, to create an effective enabling environment for AI, an internationally accepted system of norms to govern both data and AI, and adopt policies to discourage anti-competitive behaviour.

The US should be leading this effort because it holds a large share of the global market for AI services. However, it is sending mixed messages.

AI is generally used to describe computer systems that can sense their environment, think, learn and act in ways that humans do. AI applications use computational analysis of data to uncover patterns and draw inferences. To “train” these systems, AI applications utilise huge volumes of data that is supposed to be high quality, up to date, complete and correct, to ensure accuracy and avoid discrimination.

Because of this huge and growing demand for training data, no nation alone can govern AI without interoperable policies to govern data, as well as hold firms to account for their potential misuse of data. America and China’s data giants achieved an early lead in acquiring such information, which in turn made it easier for them to capture a large share of the global market for AI.