Advertisement

Opinion | Carrie Lam’s mask ban is an ineffective stick for violent protesters. Where’s the carrot for moderate protesters?

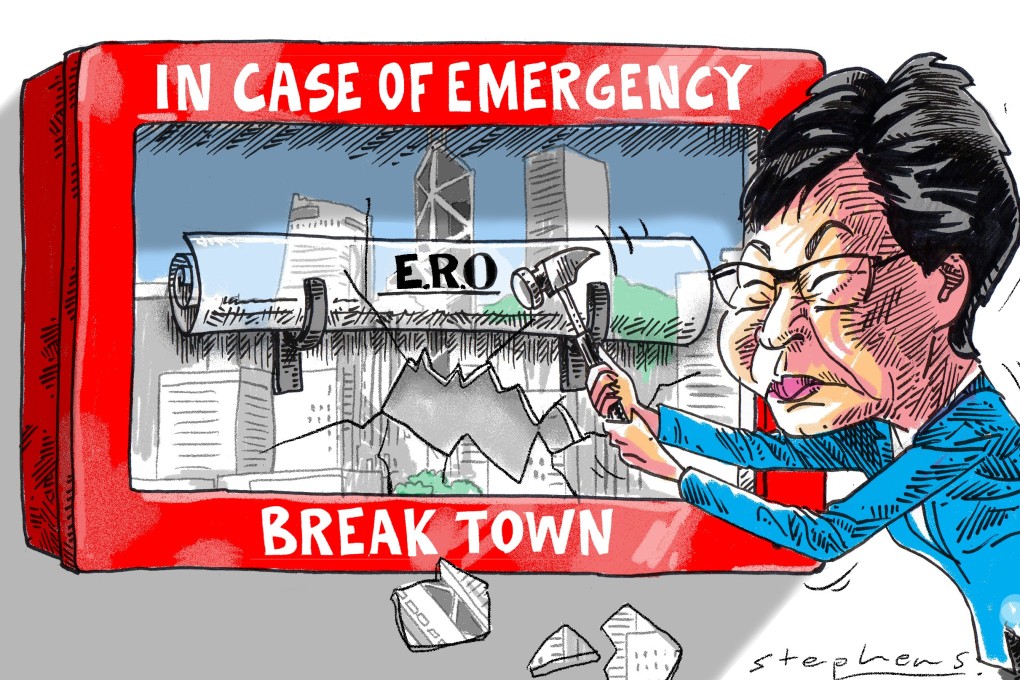

- The use of a colonial-era emergency law has raised tensions at a time when Hong Kong needs to calm down. In invoking the draconian law from 1922, the Hong Kong government should draw the right lesson from history

5-MIN READ5-MIN

The deepening political divisions in Hong Kong leave little room for a consensus on anything. But one point which both sides can agree on, after four months of anti-government protests and escalating violence, is the need for the government to act. Something has to be done.

Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor has faced growing pressure from her pro-establishment allies to take a tougher line and to invoke colonial-era emergency laws in a bid to end the violence. Democrats and protesters, meanwhile, have called on her to meet their demands.

The push for a crackdown, no doubt, intensified during Lam’s visit to Beijing to mark the 70th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China. As she celebrated, Hong Kong burned.

Advertisement

Three days later, the Emergency Regulations Ordinance was invoked for the first time since the 1967 riots. The dusting off of this outdated and draconian legislation, passed in one day in 1922, is a dangerous step. Despite assurances from the government that it will be used cautiously, there are understandable concerns that now it has been triggered, further measures will follow.

The ordinance, first used by the colonial authorities to crack down on a seamen’s strike, empowers the chief executive to make “any regulations whatsoever” which she may consider desirable in the public interest. This can be done on “any occasion” the chief executive considers to be of emergency or public danger. The scope is breathtaking. It is difficult to see how it can be reconciled with the human rights protection provided by the Basic Law and Bill of Rights.

There were calls in the 1990s for the law to be repealed by the colonial administration. Even more draconian regulations made under it in the 1940s and 1960s were removed. But the ordinance, described by democrat Martin Lee Chu-ming as a landmine, was left in place. One columnist wrote in the Post at the time that this was done as a “futile conciliatory gesture towards Beijing”.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x