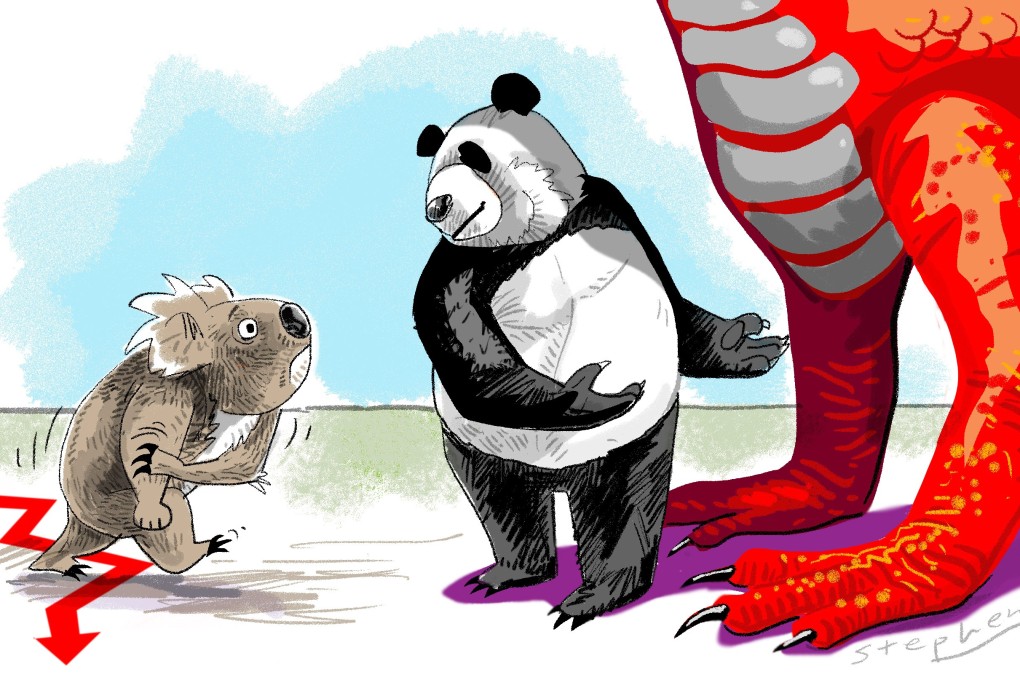

Opinion | As Australia pushes back against China, the Western world is watching to see Beijing’s response

- China’s growing confidence to deploy economic sanctions against countries that refuse to toe the line is worrying many. Australia is countering this, in a limited sense, but when push comes to shove, will all the talk about getting tough on China turn out to be bluster?

China’s economic statecraft has been shaped not just by its recent surge in wealth. Beijing has watched for decades how Washington wields sanctions against other countries to attempt to bring them to heel. The Chinese remember well how the United States imposed an oil embargo on Imperial Japan in 1941 in response to its occupation of China and Southeast Asia. The attack on Pearl Harbour followed soon after.

From the time the Communist Party of China took office, its leaders learned the hard way about how trade could be used as a diplomatic weapon. Amy King, senior lecturer in strategic and defence studies at Australian National University, says of that period that Communist Party leaders “had not anticipated the US-led embargo, and, when it came, were surprised how quickly it disrupted the Chinese economy”.