Advertisement

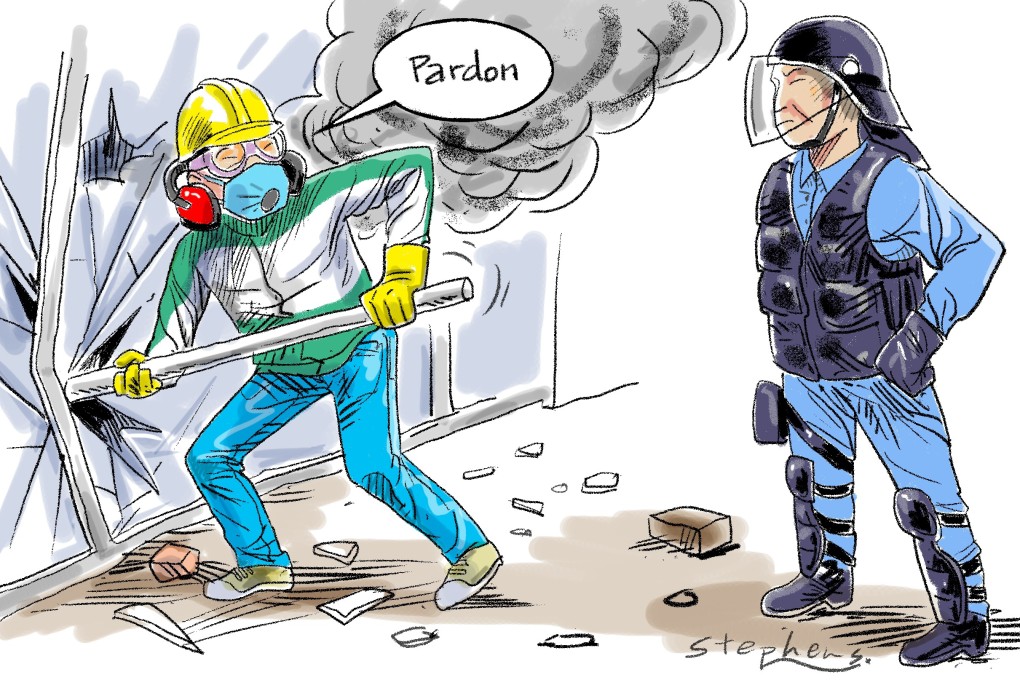

Opinion | Hong Kong protests: calls for an amnesty or a pardon for those convicted must be resisted

- Apart from the potential backlash and waste of courts’ time and money, granting a pardon or amnesty to those convicted of protest-related crimes would constitute a manipulation of procedure and hurt the integrity of Hong Kong’s criminal justice system

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

While visiting Shanghai, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor again ruled out a general amnesty to people arrested over the civil disturbances. She was right to do so, as the idea that people who commit grave crimes should escape their just deserts is repugnant to the rule of law. Had she decided otherwise, the message would have gone out that political violence is less abhorrent than other types of violence.

Although advocates of an amnesty invariably point to the one granted to corrupt police officers in 1977, that sorry episode provides no sort of precedent. After the Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) headquarters were attacked and its staff assaulted, a police mutiny was threatened if its investigations were not curtailed. Faced with such intimidation, the governor, Sir Murray MacLehose, had no choice but to tell the ICAC to end many of its investigations. It was a black day for the legal system, and one which will hopefully never be repeated.

Moreover, in contrast to 1977, many of the protest cases are now before the courts. In the event of amnesty, the chief executive would have to instruct the secretary for justice to terminate the prosecutions, but this would be unconstitutional.

Advertisement

Since 1997, the Basic Law has provided both the Department of Justice and the ICAC with the constitutionally guaranteed independence they lacked in 1977. Whereas Article 63 provides that the Department of Justice “shall control criminal prosecutions, free from any interference”, Article 57 stipulates that the ICAC “shall function independently”. Since, moreover, Article 48 (2) requires the chief executive to implement the Basic Law, any attempt to interfere with ongoing prosecution would be unthinkable.

Although the police force does not enjoy the same protections as the ICAC, its mandate, nonetheless, requires it to detect crimes. Any attempts, therefore, by the executive to terminate its investigations would not only be improper, but would also trigger a huge backlash, including in the police force, given that its officers and their families have recently been the victims of crime.

However, an alternative possibility, of granting pardons to convicted protesters, or at least some of them, has now been mooted. This, presumably, is seen as a sop, given that an amnesty is out of the question. It is, however, no less of concern, and must also be excluded as an option, save, perhaps, in the rarest of cases. Any pardon must be subject to the strictest criteria.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x