Advertisement

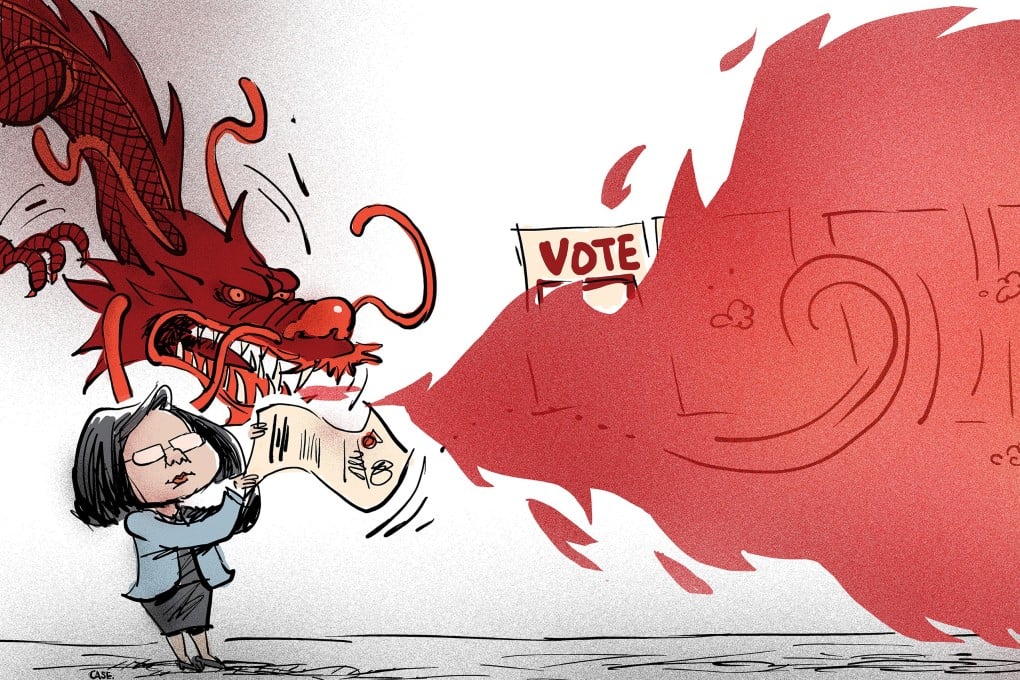

Opinion | Taiwan’s new anti-infiltration law seeks to curb Chinese communist influence, but it may end up hurting democracy

- While supporters point to Chinese misinformation campaigns to justify the law and point to its narrow scope, the way it was rushed through and the chilling effect it will have on freedom of speech and cross-strait exchanges are cause for concern

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

With less than two weeks to go before Taiwan’s presidential and general elections, the Democratic Progressive Party rammed its anti-infiltration law through the legislature in 34 days. Its opponents have derided the rushed process as an election ploy.

Inspired by the US Justice Department ordering Chinese state media to register as “foreign agents” under the Foreign Agents Registration Act, Taiwan’s new law is the last leg of DPP-sponsored anti-China legislation that included five amendments to various national security laws in 2019. The anti-infiltration bill gained momentum after Hong Kong’s anti-extradition bill protests and the defection of self-proclaimed Chinese spy Wang Liqiang to Australia in late November.

The sweeping legislation criminalises those who help “external hostile forces” organise political activities, disrupt social order or lobby lawmakers. The crimes carry a maximum sentence of a NT$10 million (US$334,688) fine and five years in prison.

Advertisement

Although the bill does not specify what constitutes “external hostile forces”, the elephant in the room is Beijing’s propaganda machine. Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen’s party is positioning itself as the protector of the island’s sovereignty against the threat of Beijing, which does not rule out seeking unification by force.

The DPP proposed the law on November 27 and denied the Beijing-friendly Kuomintang’s counterproposal of an “anti-annexation law” on December 6. On December 14, Tsai announced that the law must be passed on December 31.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x