Advertisement

Opinion | How to prevent US-China rivalry from turning Southeast Asia into a conflict zone

- Both powers need to publicly agree on anti-hegemony, settle on ‘rules of the road’, particularly in the South China Sea, and start discussing arms control

- Beijing and Washington must not sleepwalk into war, or force Southeast Asia to choose sides

4-MIN READ4-MIN

In Singapore, we recently gathered thought leaders from Southeast Asia, China and the United States. The meeting’s purposes were to understand how the intensifying US-China strategic friction is affecting the region, and to suggest ways to put developments on a more positive trajectory.

The US and China are in what Henry Kissinger recently called “the foothills” of a cold war. Grey-zone conflict – coercion exerted by means just short of undeniable military force – is mounting in Southeast and East Asia. The prospects for accidents or miscalculation grow.

Moreover, the deteriorating US-China security relationship is spilling over into their economic and cultural ties, with increasing ramifications for regional neighbours and beyond. While the recent US-China phase-one trade deal is broadly welcome, it leaves many issues unresolved, and Southeast Asians and others worry that the two powers will sleepwalk into progressively greater conflict. They fear being pressured into taking sides.

Advertisement

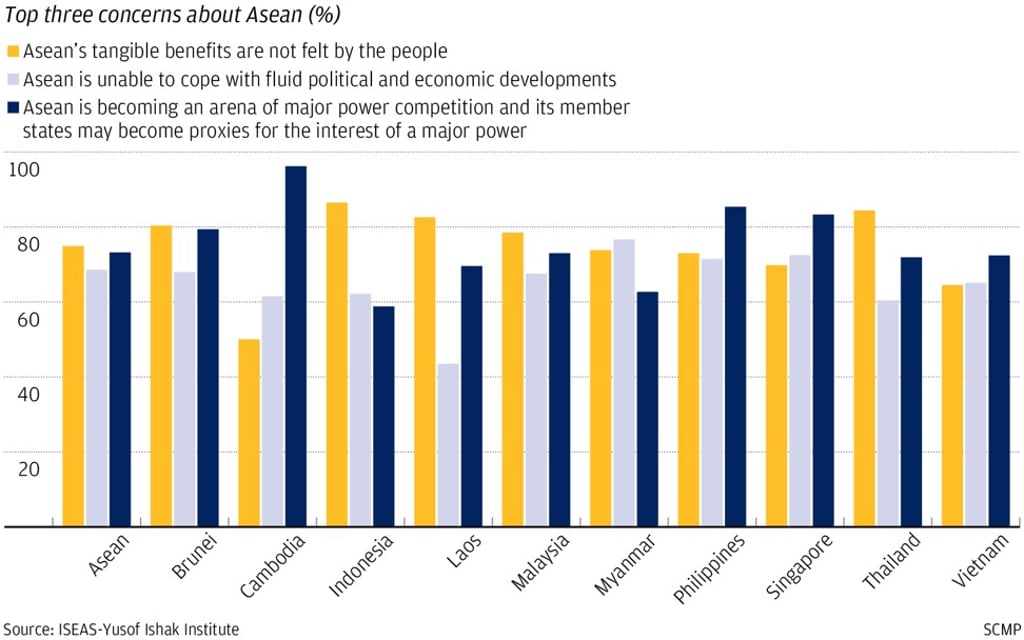

Southeast Asia accepts that the US and China have a competitive relationship and that there is no prospect of quickly reversing this circumstance. But these nations look ominously to the horizon where they see a tech war looming, and they see themselves as increasingly likely to be drawn into economic struggles and possibly military conflict.

Advertisement

They wish to avoid these escalations at all costs. They believe that if Sino-American ties stabilise, they will be able to use their well-honed navigational skills to survive in the space between the two powers. So they want Beijing and Washington to develop a modus vivendi, even if warmth is unachievable.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x