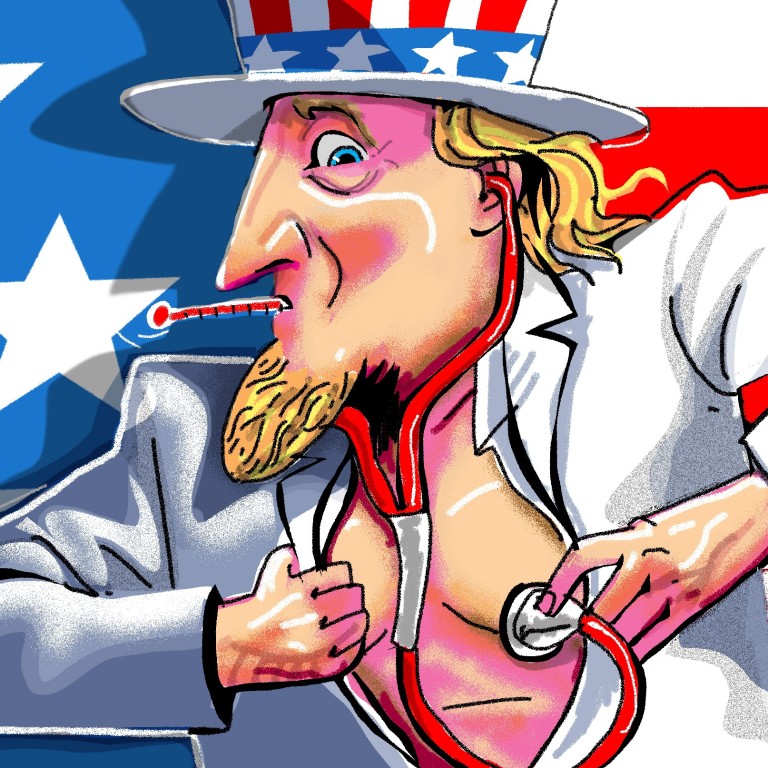

Why the coronavirus is a ticking time bomb in the US: a costly and inefficient health care system

- The US’ slow initial response to the threat of Covid-19, the shortage of testing kits and confusion over who can get tested are symptoms of long-term structural problems in the country’s health care system

Is this true? While the US has some of the world’s best medical scientists, research institutions and pharmaceutical innovations, its health care system is too fragile to protect its citizens from any epidemic.

Frustrated by multiple rejections from the authorities even as the outbreak exploded in other countries, Chu decided to perform the tests without government approval in late February. A test from a teenager, who had no recent overseas travel, came back positive.

Six weeks after Chu began trying to get around bureaucratic red tape, the coronavirus has killed 37 people and infected over 500 others in Washington state.

One can understand the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Food and Drug Administration not allowing private labs to run the tests. Quality concerns aside, they might have wanted to centralise efforts to combat the epidemic.

So why, despite all the signs that a national health crisis was brewing, was so little done to contain the epidemic early on? This is an acute symptom of long-term structural problems in the US health care system, rather than the result of bipartisan politics or Trump.

According to Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development statistics, the US is an outlier in health care spending. Americans on average spent US$10,586 on health care in 2018, double the OECD average and 45 per cent higher than Switzerland, the second biggest spender among developed nations.

Why do Americans spend so much on health care? One explanation could be that they use health care services more. However, research has revealed that, compared to people in other wealthy countries, Americans tend to have shorter hospital stays for the same medical procedures and pay fewer visits to doctors.

The US compares badly to other developed countries on all measured health outcomes, including life expectancy, unmanaged asthma and safety during childbirth.

One reason for high US health care expenditure, but poor outcomes, are the high administrative costs. Americans on average spent US$800 per year on health care administrative costs, compared to less than a quarter of that in other wealthy countries.

Another reason is the profit-driven US health care ecosystem. Insurance providers, pharmaceutical companies and even hospital conglomerates dominate the sector. Doctors are encouraged to perform more procedures that are billable to insurance companies.

Drug companies and even federal agencies are less likely to support research in vaccines for epidemics that happen every decade or so, compared to funding research that promises a constant stream of revenue, such as cancer research.

The inefficiency of the US health care system may have gradually shaped the psychology of most Americans towards illness. During the 20 years I lived in the US, whenever I had flu-like symptoms, I tended to buy over-the-counter medication from a chemist instead of seeing a physician.

If people do not expect to be tested for the coronavirus after hours of negotiations, they would not even try to seek testing. There will probably be many hidden coronavirus carriers even when tests become widely available.

US starts clinical trial of Covid-19 vaccine that will last into next year

It’s not surprising that this distorted health care system cannot respond more quickly and flexibly to the epidemic. Health authorities are used to setting up entry barriers, under the influence of lobbyists.

Trump advises against social gatherings of more than 10 people

Meanwhile, complex insurance policies add to confusion about who will bear the cost of private testing and treatment for those infected.

The US government has reacted more aggressively to the outbreak since Trump’s address on March 11. In the next few weeks, we are going to see a spike in the number of confirmed infections. Research by the CDC in collaboration with epidemic experts in February suggested that, eventually, between 2.4 million and 21 million Americans could require hospitalisation.

A more updated exercise by a research team at Northeastern University, after taking into account the US government’s recent aggressive intervention and the speed of the epidemic’s evolution, shows that even in the best scenario, the number of detected infections will be over 150,000 by April 30.

Given the less than 1 million staffed hospital beds in the country and the 64 per cent occupancy rate, the surge in demand for coronavirus-related hospitalisation will stress the health care system, crowding out other urgent medical services.

The US government should leverage the lessons learned during this epidemic to reform its health care system. If China could do it after the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic in 2003, there is no excuse for the US not to do so.

Heiwai Tang is professor of economics and associate director of the Institute for China and Global Development at the University of Hong Kong