Advertisement

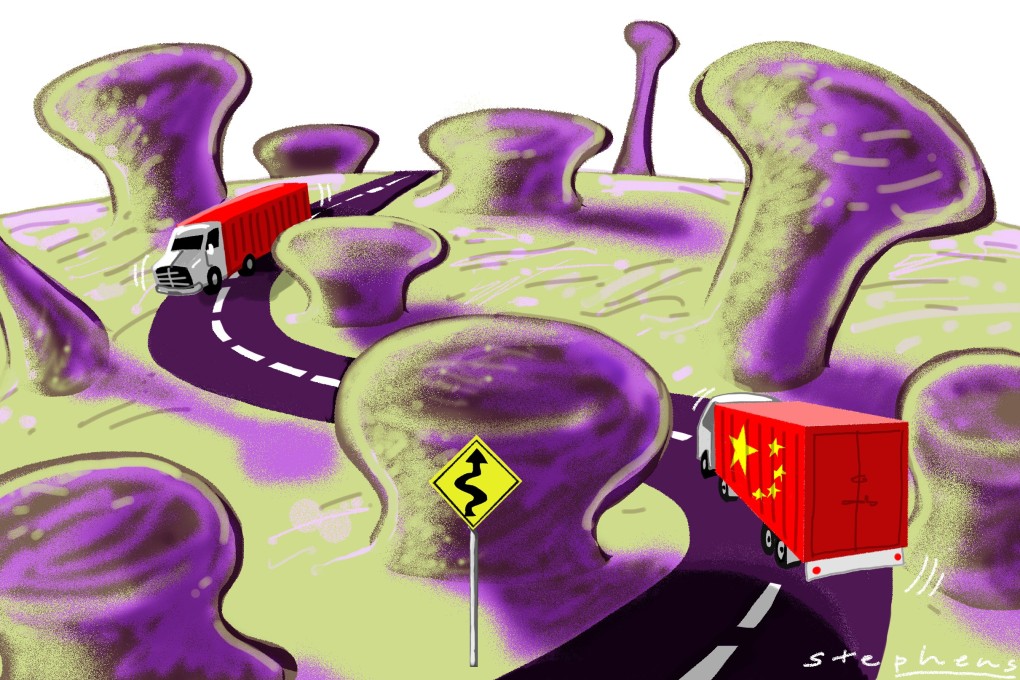

Opinion | The coronavirus will not be fatal for China’s Belt and Road Initiative but it will strike a heavy blow

- Projects face delays as the coronavirus prevents Beijing from supplying goods and people. And project resources will be diverted as China focuses on its own recovery. But the biggest casualty may be a loss of faith in Chinese-style connectivity

4-MIN READ4-MIN

Suddenly, a highly infectious virus has become China’s most prominent export. What began on January 3, when China reported 44 cases of pneumonia in Wuhan, has become the Covid-19 global pandemic. Wuhan, the manufacturing centre that helped to power China’s flagship Belt and Road Initiative, has become the epicentre of a health crisis shutting down many of those projects.

The corridors that facilitate the flow of goods can be conduits for pathogens and disease. As Covid-19 spreads, is the Belt and Road Initiative at risk of becoming an infection thoroughfare?

Chinese officials have been at pains to assure the world that, as Foreign Minister Wang Yi said in mid-February, the virus will have not have “any negative impact” on belt and road projects. Others have offered assurances that the adverse economic impact is only temporary.

Advertisement

Yet the authorities are aware that the outbreak is causing difficulties for overseas projects. On March 2, China Development Bank said it would provide low-cost loans to affected belt-and-road-related companies, although presumably these will go mainly or exclusively to Chinese firms.

Foreign officials are blunter about Covid-19’s impact. In Bangladesh, the transport minister warned that a billion-dollar bridge project was under threat. In Nigeria, a major rail project was put on hold. Pakistan’s planning and development minister said the US$62 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor faced delays. Indonesia’s investment minister has also announced delays for the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed rail project.

Reports from belt and road projects document a host of problems resulting from Covid-19. Managers, engineers and construction workers in China for the Lunar New Year holiday have been delayed or prevented from returning by travel bans and quarantines.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x