Advertisement

Opinion | US’ Taipei Act is a needless provocation aimed at China, even if unintended

- The Act’s unanimous passage in Congress and a study of its provisions make clear the legislation is largely symbolic. But will Beijing see it as such?

- The people of Taiwan need to ask themselves: if Beijing reacts muscularly to the US move, what is the US actually prepared to do?

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

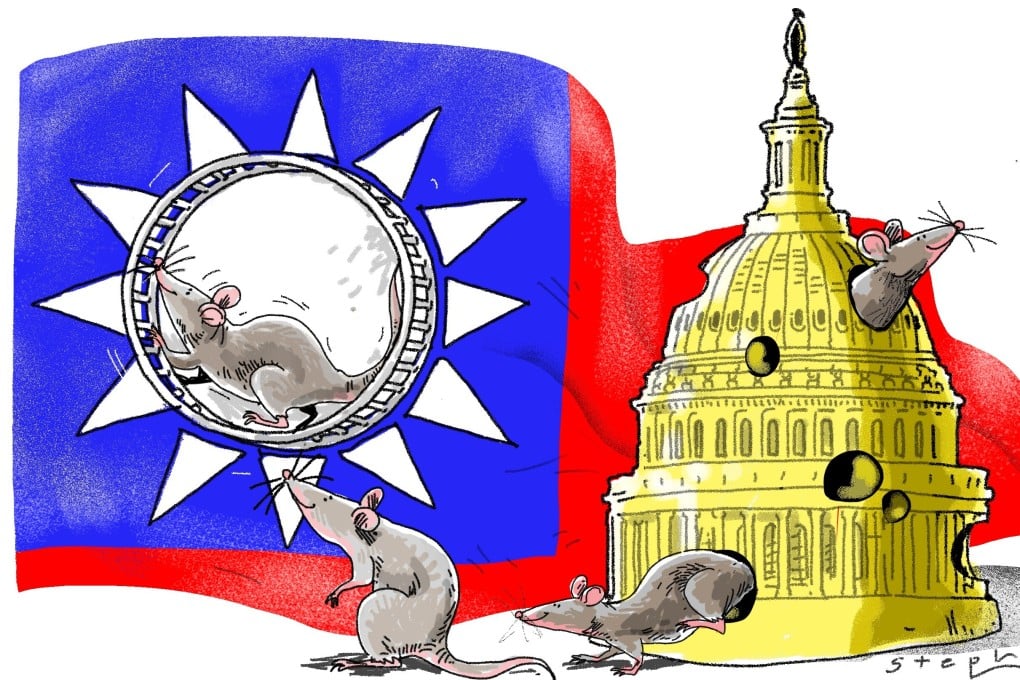

While the cat of the US Congress has been preoccupied with the global pandemic, and rightly so, the mice in its halls have been playing with Taiwan policy. By unanimous votes of both houses of Congress, the Taiwan Allies International Protection and Enhancement Initiative (Taipei) Act of 2019 was passed, sent to US President Donald Trump, and signed into law on March 26.

This development has proceeded with little or no public commentary. One could be forgiven for thinking the absence of discussion is deserved. When anything passes both houses of Congress by unanimous vote, one can rightly suspect that zero thought has gone into the move and that it is intended to be largely symbolic.

That is, members of Congress (along with the president) believe that they can satisfy domestic sentiment and incur little or no cost internationally – a “freebie”. Someone on the Hill must have stayed up all night dreaming up a name for the Act that, when put in acronym form, spelt out the name of Taiwan’s capital Taipei.

Advertisement

While being viewed symbolically in the US, the law may be viewed very differently on China’s mainland. Beijing ultimately gets a say in what ends up being symbolic and what does not. What if Beijing believes Washington is testing its red lines on Taiwan policy? What if Beijing believes Washington seeks to take advantage of China in its perceived moment of weakness – pandemic, slowing economy and subsurface popular dissatisfaction?

What if Chinese Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping believes that confronting US “bullying” and Washington’s “breaking” of long-standing agreements and understandings concerning Taiwan is good politics for him at home? What if Xi believes Trump to be weak and vacillating, Congress gridlocked, and America weakened by the serial challenges of the global financial crisis (2008-09), pandemic, economic downturn and Trump’s misrule?

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x