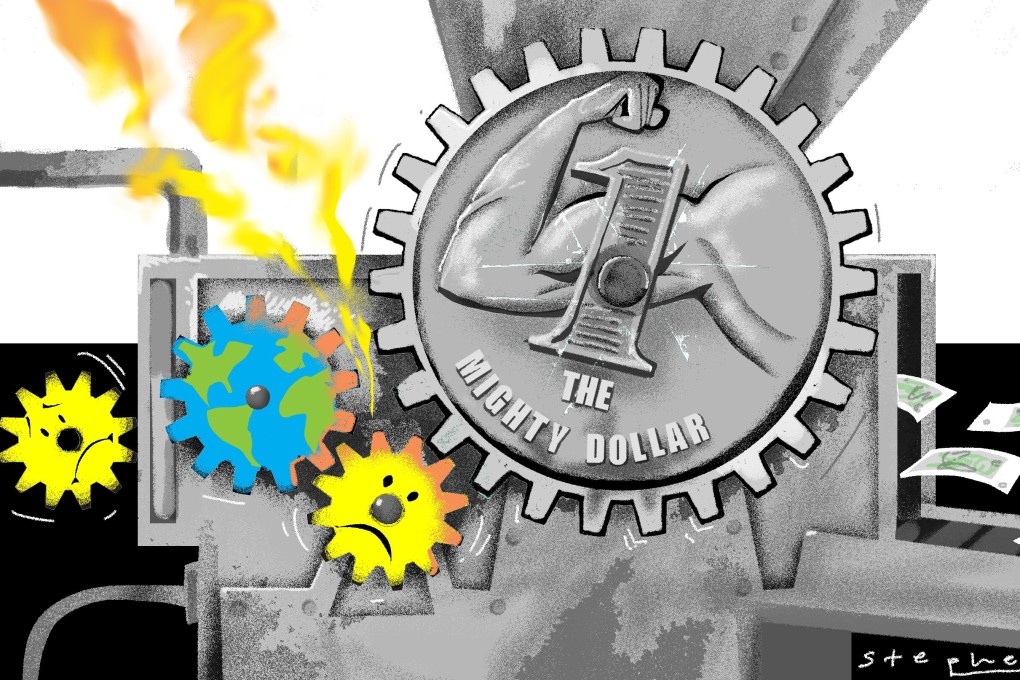

Opinion | Covid-19 pandemic shows why people and the environment should be at the heart of business

- Prioritising profit imperils people and the planet. As firms reach for bailouts, they must be required to democratise, to give workers an equal say with investors, and adopt strict environmental standards

- Meanwhile, a job guarantee scheme that gives all people access to work would allow them to live with dignity

One of the central lessons of the current crisis is that working humans are far more than “resources”: the people keeping life going through the Covid-19 pandemic prove daily that work cannot be reduced to a commodity.

By involving employees in decisions relating to their lives and futures in the workplace – by democratising firms. By decommodifying work – collectively guaranteeing useful employment to all.

Each morning, men and women rise to serve those among us who are able to remain under quarantine. The dignity of their jobs needs no other explanation than that eloquently simple term, “essential worker”.

01:28

In it, we see that human beings are not one resource among many: without labour investors, there would be no production, no services, no businesses at all. And each morning, quarantined men and women rise in their homes to fulfil the missions of the organisations they work for.