Advertisement

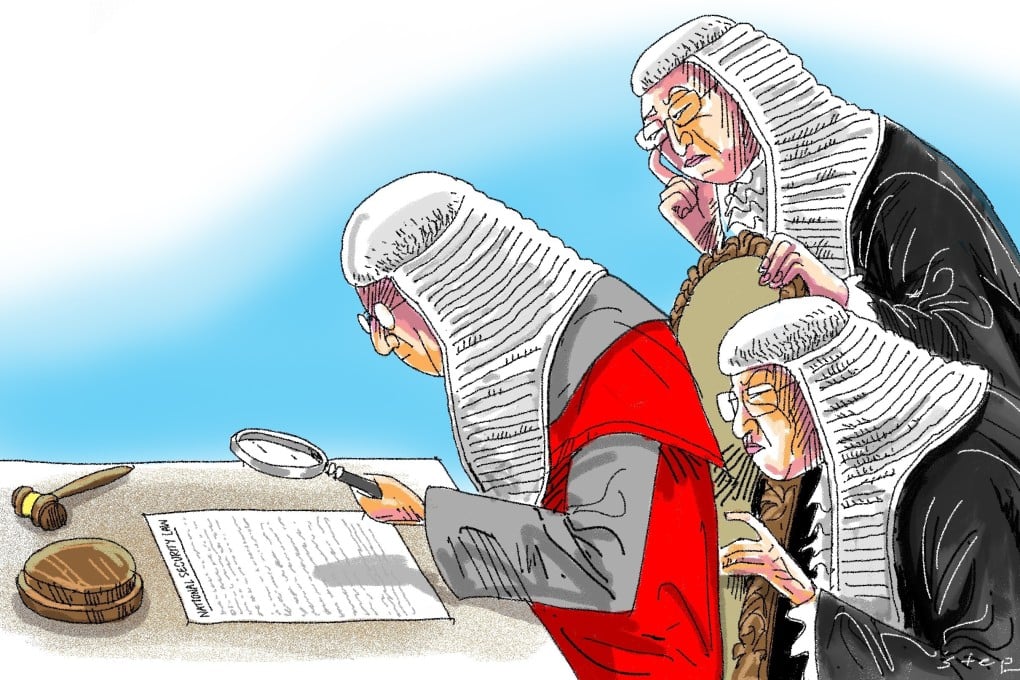

Opinion | Why Beijing must respect Hong Kong courts’ interpretation of national security law

- It is neither practical nor necessary to obtain expert evidence or an NPC Standing Committee interpretation each time an ambiguity arises in a national security case

- Respect for Hong Kong’s authority to discharge its duties under the new law requires the NPC exercise restraint in its power of interpretation

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

Like a signal No 8 typhoon, the national security law directly hit Hong Kong just before midnight on July 1, leaving us to pick up the pieces. One of those pieces is its interpretation.

Some have asked why bother as it is like other Chinese laws – vague and open to manipulation through interpretation by the authorities. Only the National People’s Congress Standing Committee appears to have the power to interpret the law. Let the political struggle continue, they say.

As a law professor and practitioner, I find such a defeatist attitude unhelpful. Cases under the new law have commenced. Lawyers need to advise on it and courts must apply it in adjudicating cases. The law is upon us and we cannot sit idle in fear, waiting for some authority to tell us what it means. In affirming our autonomy, questions of interpretation should be carefully considered on our own in accordance with existing legal practices and principles.

Advertisement

The national security law has been added to Annex III of the Basic Law by the NPC Standing Committee. Annex III national laws are to be “applied locally” – that is, by reference to local circumstances and standards. Hong Kong judges and practitioners work in a common law legal system, having been educated and trained in the common law tradition.

Few will have obtained mainland legal qualifications or studied more than an introductory course on mainland law. Few Hong Kong lawyers have experience practising law on the mainland as admission and practice is strictly regulated. When questions of mainland law arise in Hong Kong litigation, like questions of foreign law, expert evidence of mainland law is required.

05:50

What you should know about China's new national security law for Hong Kong

What you should know about China's new national security law for Hong Kong

This bifurcation of legal systems is a direct and intended consequence of the Basic Law, which directs that the “socialist system and policies shall not be practised” in Hong Kong. As recognised by our Court of Final Appeal, many Basic Law articles are devoted to establishing Hong Kong’s separate system, of which guarantees of rights and freedoms lie at its heart.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x