Why Asia’s rapidly growing bond markets are still vulnerable to financial stress

- Asian bond markets have grown massively since the 1997 currency crisis but remain dominated by government bonds and, while attracting huge foreign investor interest, also expose countries to capital flight

For instance, one key objective of the Asian Bond Markets Initiative launched in December 2002 has been to foster the development of local currency bond markets and recycle available savings in the region to support long-term infrastructure investments. The initiative has since been updated to refocus on specific bond market development issues. Another significant initiative is the Asean+3 Bond Market Forum, established in 2010 to standardise market practices and harmonise regulation of cross-border transactions.

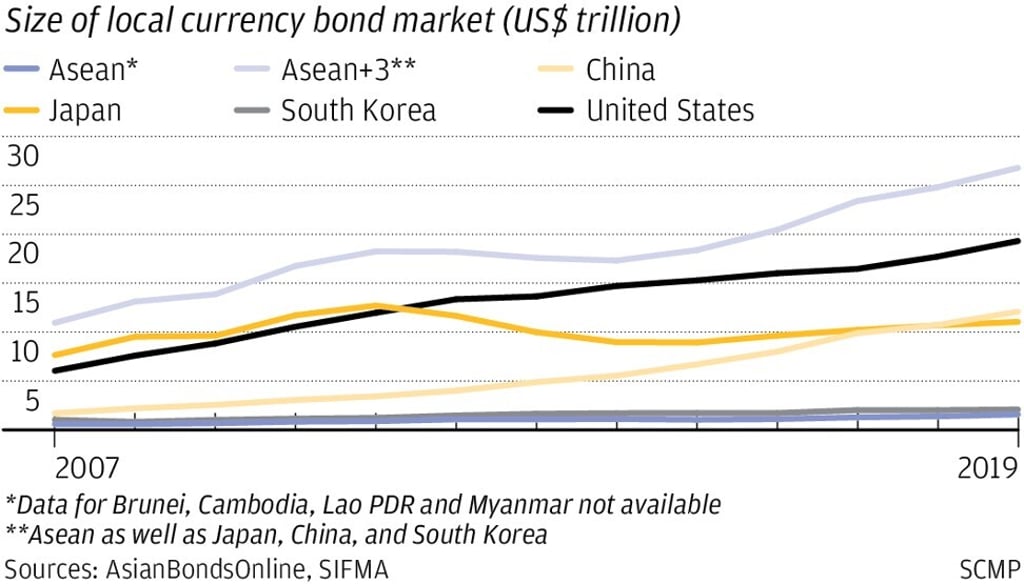

These policy initiatives appear to have borne fruit. For instance, Asean+3 local currency bond markets have grown considerably. In absolute terms, the aggregate value of Asean+3 outstanding local currency bonds exceeded US$26 trillion last year, surpassing those of the US at around US$19 trillion. As a share of gross domestic product, local currency bonds issued in the Asean+3 region have on average increased from a little over 45 per cent in 2001 to nearly 90 per cent last year, comparable to that of the US.

While local currency bond markets in many Asean+3 economies have grown rapidly (with Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar being laggards), they remain largely dominated by government bonds. This is not to suggest that corporate bond markets have not expanded. While the average annual growth rate of local currency government bonds between 2001 and last year was around 15 per cent, corporate bonds grew nearly 40 per cent. During the same period, local currency corporate bonds as a share of the region’s output more than doubled, from 13 per cent to 27 per cent.

Despite the rapid growth of the corporate bond market, several concerns remain. First, while the investor base has broadened notably, there is a lack of diversity. In particular, banks by and large remain the single largest investor in corporate bond markets, though domestic institutional investors such as pension funds and insurance companies are emerging.

Second, the maturity profile of local currency corporate bonds is generally lower than those of local currency government bonds in the region. With a few exceptions – such as Malaysia, the Philippines and Singapore – more than 40 per cent of corporate bonds on average (between 2008 and 2018) in other Asean+3 countries have maturities of between one and three years, while those of local currency government bonds are typically above five years.