For all the bluster, Donald Trump’s Hong Kong sanctions may not amount to much

- A sanctions war seems to be brewing between the US and China. But on closer inspection, some US measures may be rather symbolic. Notably, the Trump administration has decided against a drastic move to undermine the Hong Kong dollar peg

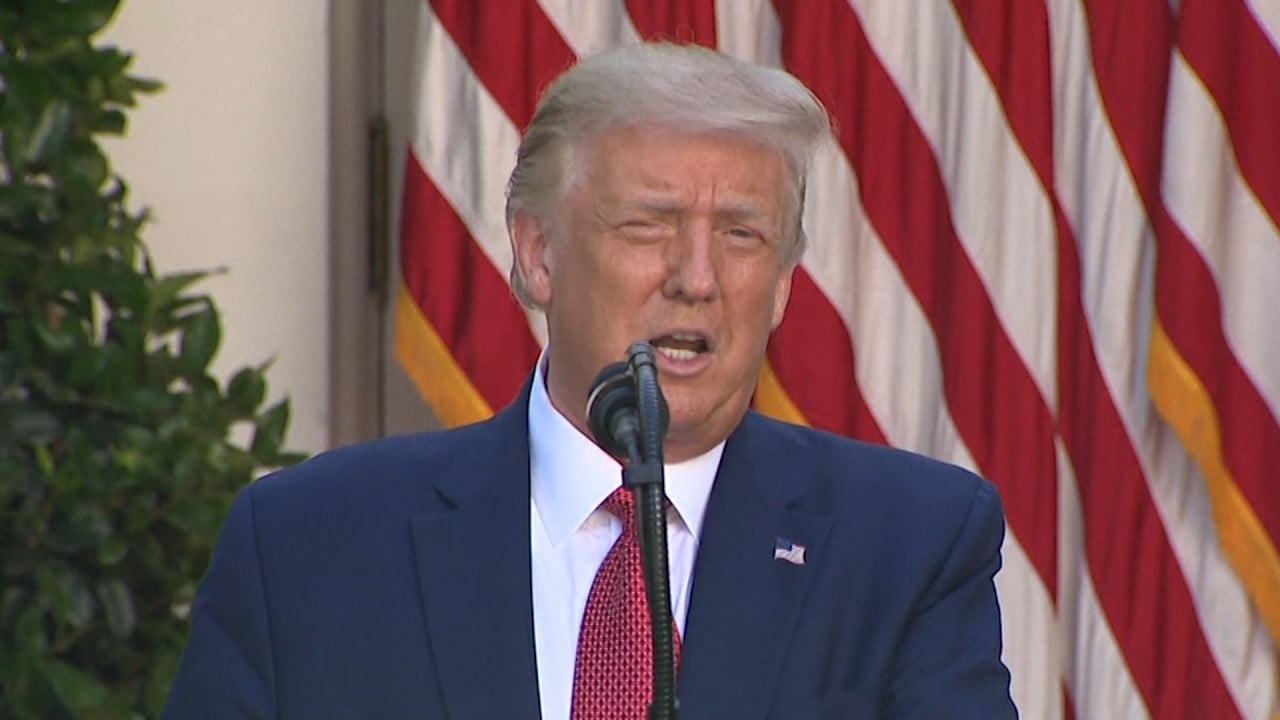

Trump simultaneously issued an executive order revoking the preferential treatment Hong Kong had enjoyed since the handover.

Widely overlooked was Trump’s invocation of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, which allows him to declare a “national emergency” with respect to Hong Kong in order to bolster the sanctions laid by Congress in the Hong Kong Autonomy Act.

02:09

Trump signs Hong Kong Autonomy Act, ends city’s preferential trade status over national security law

This enables the president to direct the State Department and the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control to add Chinese and Hong Kong individuals and entities to the List of Specially Designated Nationals, popularly known as the SDN list.

To put it simply: you do not want to find yourself on the SDN list. Your assets under US jurisdiction are frozen. US citizens are prohibited from dealing with you, directly or indirectly, anywhere in the world. You and the companies you own are economic pariahs, cut off from the US financial system and consequently from most of the international financial system as well.

In other words, the restrictions on “property transactions” that form the backbone of the Hong Kong Autonomy Act sanctions have now been supplemented by the far harsher SDN list penalties. If Congress had community service in mind for Chinese and Hong Kong officials, Trump has just threatened them with hard labour.

Consider the following doomsday scenario: the US places a large group of prominent Chinese and Hong Kong officials on the SDN list. Some of these officials beneficially own accounts in the Hong Kong branches of US financial institutions.

Under those circumstances, financial institutions that are subject to US law would be stuck between a rock and a hard place, and many could decamp to Singapore or elsewhere. Hong Kong’s status as a global financial hub would begin to erode.

US businesses caught in the middle may lobby the US government for a more moderate China policy. It seems unlikely that Beijing would choose to sanction leading global investment banks, which have spent decades helping China.

Similarly, the US may hesitate to sanction China’s big four state banks, jeopardising their combined US$1.1 trillion of US dollar deposits, interbank borrowing and overseas debt.

Second, many global financial institutions have experience navigating conflicting sanctions regimes. The EU blocking statute provides one example.

Third, depending on how the sanctions are applied, non-US financial institutions may be able to ring-fence accounts of sanctioned people.

03:39

Hong Kong Legislative Council elections postponed by a year

Finally, some US measures, while headline-grabbing, appear to have more of a symbolic impact. US tariffs will now apply to Hong Kong exports, but Hong Kong is one of the few trading partners with which the US has consistently enjoyed a significant trade surplus. Trump’s order also targets extraditions, which would affect a grand total of one or two cases a year.

Nick Turner is a Hong Kong-based registered foreign lawyer whose practice focuses on economic sanctions law. Joshua M. Zimmerman is a former corporate lawyer who has resided in Hong Kong since 1997

David Dodwell is on holiday