My Take | What geometry can teach us about rights, equality and politics

- Appealing to self-evidence is no royal road to truth, rather it can lead us astray, into falsehood

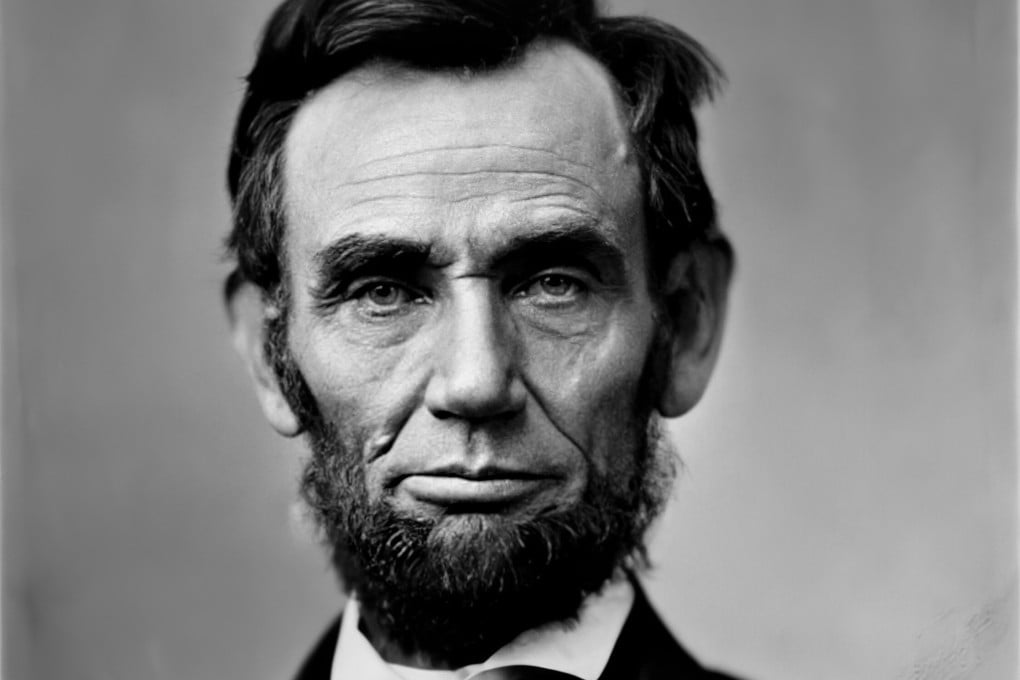

There is the old chestnut about Abraham Lincoln learning Euclid’s geometry to understand logic and reasoning better. More importantly, he wanted to know what the US constitutional framers meant by “self-evident” and “all men” (or universality).

By the time he entered Congress, he had mastered the first six books of the Elements, which has a total of 13 books (or chapters). While it was no doubt admirable for an adult, any adult, to aim at self-improvement, it’s not for nothing that this greatest of maths textbooks has its particular title: it is elementary.

Most intelligent schoolchildren, if they are so inclined, can probably work through all the propositions in the Elements, given time and patience. There is a reason for that. Most of the “proofs” in the text would not have passed muster with professional mathematicians, not just today’s but those in the 19th century, when Europeans such as Cauchy and Weierstrass started setting rigorous standards of maths proof.

As the great logician and philosopher Bertrand Russell once said, few propositions in Euclid deserved to be taken seriously. One exception is the fifth postulate, the one that your primary schoolteacher might explain as “parallel lines never meet”. There are five postulates at the beginning of the Elements.

Americans, from the inception of their country, have always insisted on dressing up self-interests with grandiose claims.

They are called postulates because they are only defined, not proved, by appealing to our “intuition” or sense of self-evidence. They are said to be needed if you want to proceed with the proofs in the rest of the text.