US-China relations aren’t likely to recover soon, whoever wins the White House

- Backed by a strong bipartisan consensus, Donald Trump has taken a scorched-earth approach to China

- But Beijing has also indicated it will not make concessions, which doesn’t bode well for bilateral ties even if Joe Biden wins the election

03:07

Stop offering ‘untrusted’ Chinese apps like TikTok and WeChat, Washington urges US tech companies

Forget a cold war. Is the US preparing for a hot war with China?

By the second half of the administration, it was clear that neither side had got what it wanted from engagement, neither had been able to deter the other, and neither had little incentive to continue to engage the other.

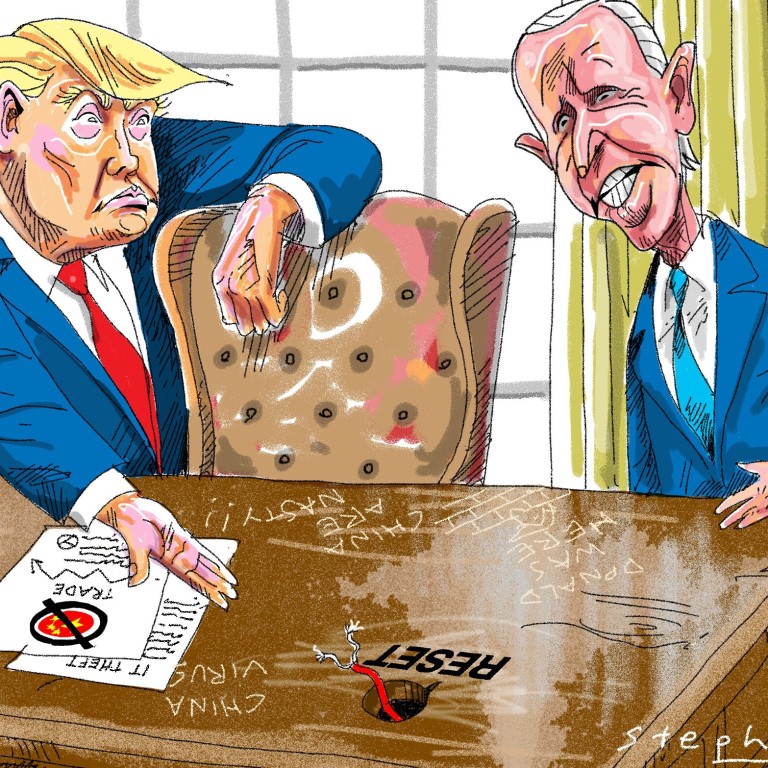

Whether Trump wins a second term or Joe Biden takes over in 2021, neither will find a reset button on relations with China on the Resolute Desk in the Oval Office after the swearing-in ceremony on January 20.

Should Trump win, he could use the start of his second term as an opportunity to bring China back to the table to test for a second time his assumptions about whether Beijing is ready to make concessions, open up its economy, stop stealing intellectual property and create a level playing field for international companies in China.

Because of his scorched-earth approach to China, Trump may find success if Beijing realises the floor of the US-China relationship could be much lower than it imagined.

Coherent policy or not, Trump got something right on China

Beijing has mastered the art of using talks to defuse tensions, but not make concessions. This could leave Biden and his team in a dilemma: they could make concessions to sustain talks or let the problem fester, they could risk being accused of doing nothing by opponents, or follow Trump’s path of steadily increasing pressure, tariffs and sanctions, cheered on steadily by Congress.

Beijing itself has made it quite clear that it is not giving Washington an incentive to bargain with China, undermining the very engagement and cooperation it is also calling for.

Both Politburo member Yang Jiechi and Foreign Minister Wang Yi have recently made remarks placing the blame for the deteriorating relationship on the US. Both have called on the US to pursue cooperation in abstract terms, without articulating what China is willing to do to actually cooperate.

01:14

US Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden takes aim at Trump’s handling of protests

Unwilling to make binding commitments to cooperate in potentially fruitful areas like the pandemic response, much less tougher bilateral issues such as intellectual property theft, industrial policy and market access, Beijing gives little indication that Washington stands to gain anything by exploring common ground in talks.

Also, China is not yet ready to give up the narrative that it was a century-long victim of foreign oppression, thereby justifying any and every action that furthers its parochial interests, even at the expense of other countries.

Regardless of who is sworn in on January 20, 2021, the US president will not inherit a bilateral relationship that is ready for improvement. Given diverging interests and entrenched positions, there will be no reset button waiting to be pushed next year.

Drew Thompson is a former US Defence Department official responsible for managing bilateral relations with China, Taiwan and Mongolia. He is a visiting senior research fellow at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore. He is on Twitter @TangAnZhu