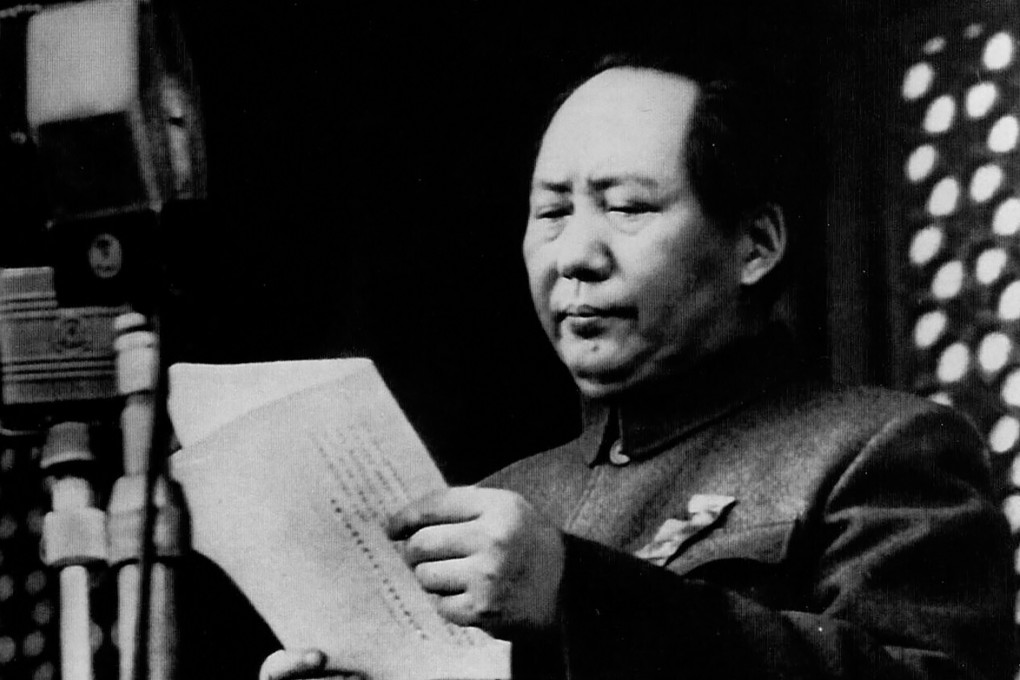

My Take | Why Mao hated random statistical sampling

- Could the great famine of 1959 to 1961 have been averted if China’s state planners had been allowed to practise proper statistics and data collection?

This is a question I sometimes ask myself ever since I read about the great Indian statistician and central planner P.C. Mahalanobis: could he and his statistical peers in China have saved the tens of millions who perished during the famine induced by the Great Leap Forward in late 1950s China?

It is not an entirely idle question in counterfactual history about what might have been. The man really was in the right time and place and could have made a big difference; and the fact that his Chinese counterparts were undermined and ignored by the Maoists helped explain why and how the famine happened.

By the mid-1950s, Chinese state statisticians realised they had collected copious quantities of data on all aspects of life in Maoist China that were also practically useless.

Among themselves, some admitted in internal communication: “Useless at the moment of creation!”

It is not that communist China lacked talented mathematicians and statisticians. Rather Maoist ideology had caused havoc to the discipline of statistics, sanctioning some methods but not others.

Crucially, it was no longer classified as a branch of mathematics, but a social science, subject to the dictates of Marxist-Leninism. This means that chance, probability and randomness, key concepts in statistics, were to be tamed, if not eliminated, under the teleological science of Marxism.