Opinion | National security law: Hong Kong’s academic freedom is safe, but the fear of losing it is harmful

- There is no compelling evidence that the new national security law has in any way impinged on the many freedoms this city’s scholars enjoy

- Academia in Hong Kong is far more free than in the United States, where research is only mostly free and professors are told to silence their political views

On August 15, I took part in a webinar organised by the University of Hong Kong Faculty of Law on the potential impact of the national security law on Hong Kong’s academic freedom. The panellists voiced strong concerns, and we were told to be proactive and that “wait and see” was the wrong approach.

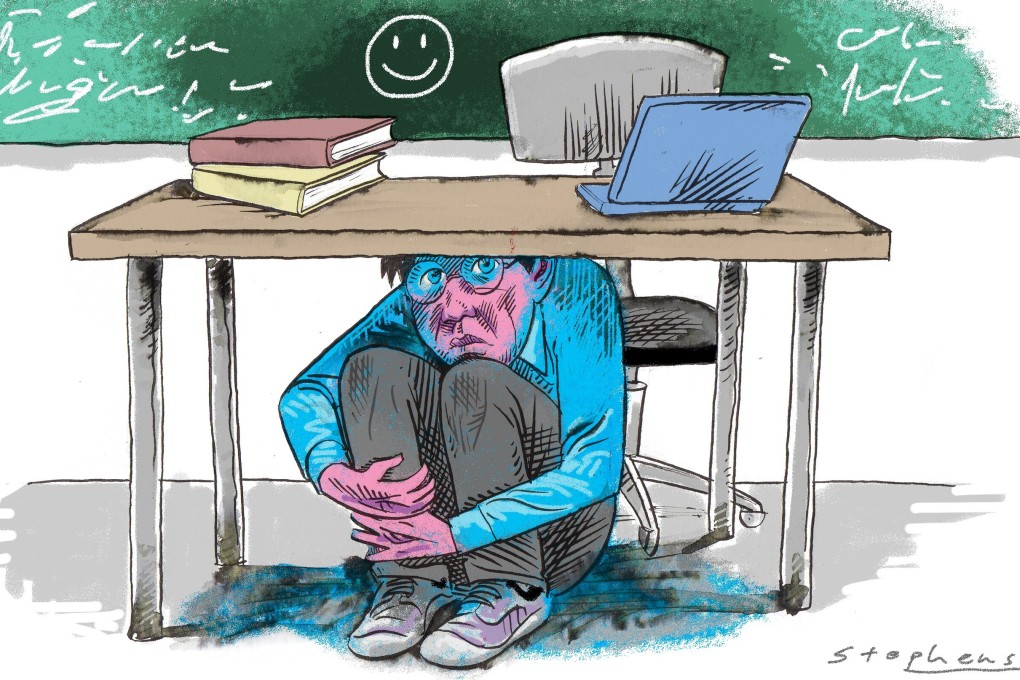

Are we really losing academic freedom? I have not seen any hard evidence of its infringement in Hong Kong.

Since 1997, there has been limited evidence of the infringement of academic freedom under the “one country, two systems” framework. The national security law specifically states that Hong Kong people’s freedom of speech will be protected. In my understanding, its limitations to political activities are designed to protect Hong Kong in case violence continues and the local legal system is incapable of stopping it.

05:50

What you should know about China's new national security law for Hong Kong

Hong Kong has more academic freedom than the United States, where I spent most of my academic career. In the US, I learned very quickly that professors should avoid advocating their political views because their authority in a classroom can put pressure on students who disagree with them. Academic research is mostly free, but not if your research is to justify the rise of Nazi Germany.