My Take | What kung fu can teach us about self-deception

- ‘Epistemic viciousness’ is an intriguing philosophical concept to keep us on our toes against false beliefs and superstitions

I am a cynical man and don’t get disillusioned easily. But after repeatedly watching practitioners of mixed martial arts and Krav Maga making mincemeat of traditional kung fu masters on YouTube, my long-time – and naive – belief in the efficacy of kung fu has been deeply shaken.

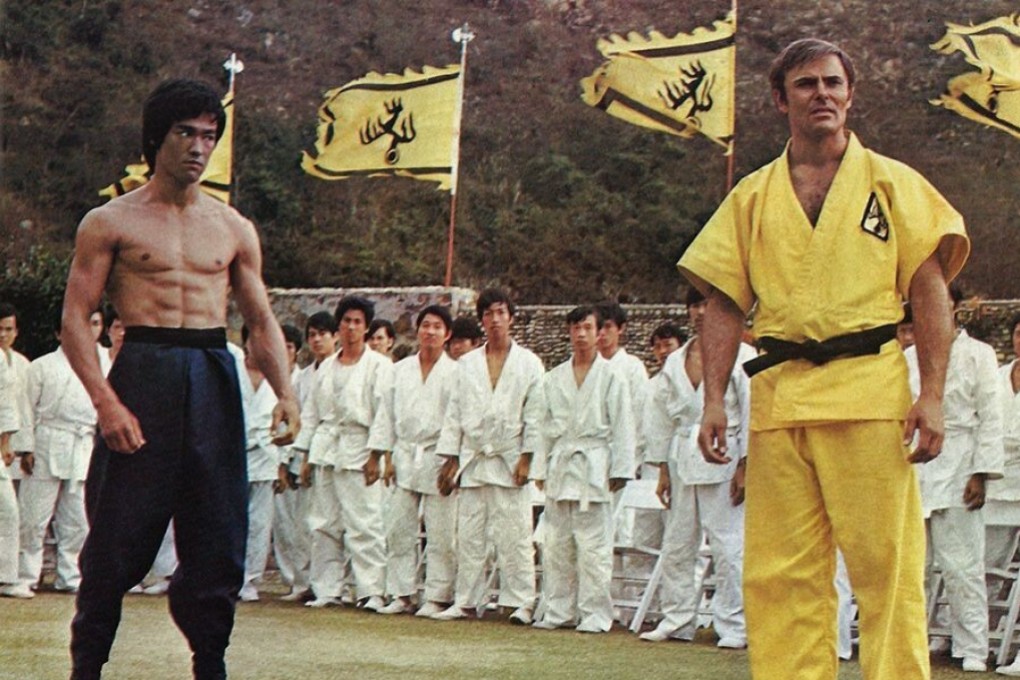

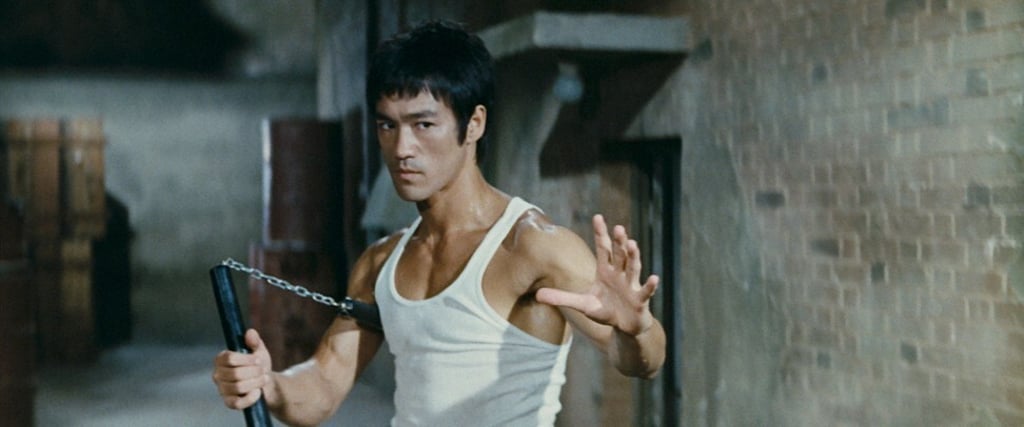

It wasn’t that I thought Ip Man could really have beaten dozens of trained fighters all at once, or that Bruce Lee could have taken on 100 judo masters and prevailed. But I had at least assumed that one on one or even one on two, they could always win.

As I started to think about my unrealistic expectations concerning traditional Chinese martial arts – well, after all, I grew up, like most of my generation, watching kung fu movies from the Shaw Brothers Studio – I found this fascinating essay, “Epistemic viciousness in the martial arts”, by Gillian Russell, a philosophy professor now at the Australian Catholic University in Melbourne.

You can find it in a collection of essays on martial arts and philosophy titled Beating and Nothingness”. (Fans of French existentialism will recognise the in-joke.)

As an 11-year-old, she told us, she worshipped her gym teacher and thought she could learn his style of fighting called shizentai yoi and be able to kill a bull with one blow. Thankfully, she grew up to become a successful academic rather than a shizentai yoi fighter.