China’s post-pandemic lesson for the world: as stimulus slows, the party winds down for stock markets

- China’s post-pandemic experience holds lessons for investors elsewhere: after monetary stimulus peaks, a squeeze on stocks’ multiples is likely to play out in developed markets too

Economic activity across the country is, according to our real-time indicators, largely back to where it was before the outbreak. China’s stocks have enjoyed a big re-rating in the process.

Investors in developed-market stocks could be forgiven for seeing these trends in a positive light. If economies such as the United States, Europe and Japan – where economic activity is currently 10 to 20 per cent below pre-crises levels – eventually catch up with China, then surely global equity markets could add to their gains.

However, all is not as rosy as it seems. To understand why, it’s important to analyse China’s experience more closely, particularly the relationship between the country’s level of liquidity and its equity valuations.

As the crisis unfolded in early 2020, China’s monetary authorities launched an extensive set of stimulus measures to counter the economic shock from the coronavirus outbreak.

03:07

Wuhan pool party shows China's ‘strategic victory’ over Covid-19, Beijing says

What’s more, it provided a total of 1.8 trillion yuan (US$270 billion) in re-lending and rediscounting facilities, as well as another 400 billion yuan to purchase uncollateralised loans, to help small businesses.

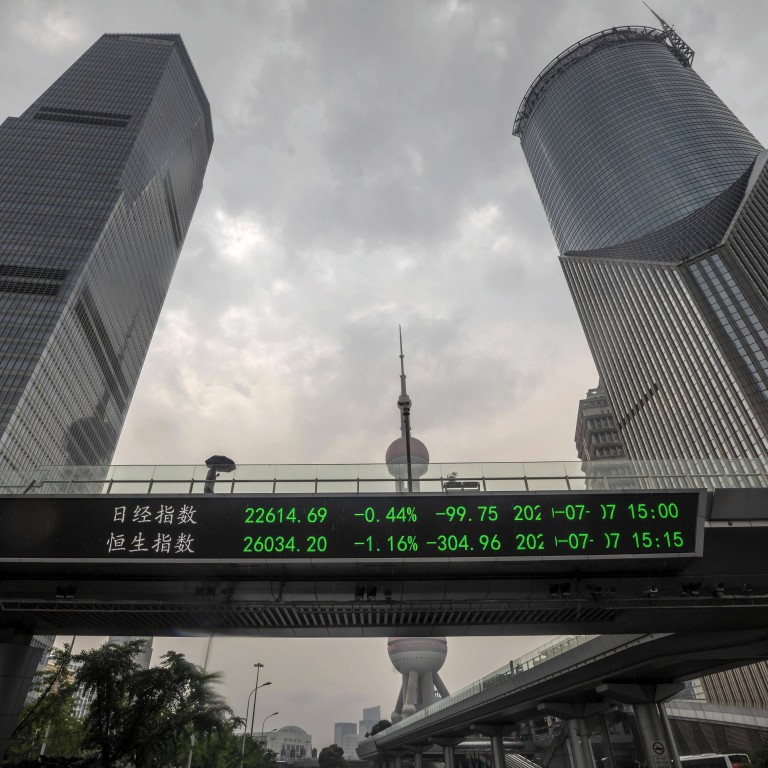

By May, the PBOC’s support package had more than halved the three-month Shibor interbank rate from the end of 2019 levels, while lifting the country’s total liquidity to a four-year high of 41 per cent of GDP – above the 10-year average.

Why People’s Bank of China is having a good pandemic

That has had a discernible effect on stock markets. With monetary support easing, the gains Chinese equities had enjoyed when stimulus was flowing – a near 30 per cent rise in the 12-month forward price-earnings ratio – now seems to have run its course. China’s benchmark CSI 300 index reached a three-year high in July but has failed to scale a new peak since.

China’s experience holds lessons for investors elsewhere: the squeeze on stocks’ multiples is likely to play out in developed markets too, and for two main reasons.

To begin with, China’s monetary policies and liquidity injections have an outsize impact on the global economy and stock market. China surpassed the US as the world’s biggest liquidity provider more than a decade ago and accounts for 40 per cent of liquidity created this year.

China printing foreign currency on massive scale to boost influence

What is more, the renminbi is gaining influence, especially in Asia. The region has effectively evolved into what we call the “renminbi bloc”, as China’s neighbouring trade partners settle contracts in yuan.

All of which means that when China slows its money supply growth, earnings multiples come under pressure, both within and outside its borders.

Then there’s the central bank’s influence on its peers across the developed world.

The world follows China with a three-month lag, our analysis shows. This means that liquidity levels in the rest of the world probably peaked in August. This creates additional downward pressure on equity multiples. That’s significant because multiple expansion has been responsible for almost all total return in the global equity market.

The S&P 500 index looks particularly vulnerable. It is already trading at a 5 per cent premium over what we consider fair value based on the current level of liquidity; this gap is more likely to narrow than widen in the coming months.

While the pace of liquidity creation may have slowed at a global level, we still expect the world’s major central banks to pump in US$1 trillion of additional liquidity between now and the end of the year, while governments will also extend fiscal stimulus, which we expect to total more than US$4 trillion this year, or nearly 5 per cent of GDP.

All of this should help cushion any potential shock to the economy and underpin financial markets. China, in particular, is well equipped to deliver targeted and coordinated measures to vulnerable industries.

Investors, therefore, should expect global asset markets to flatten out at current levels into the year end, rather than to extend a breakneck rally they have experienced since March.

Steve Donze is senior macro strategist at Pictet Asset Management