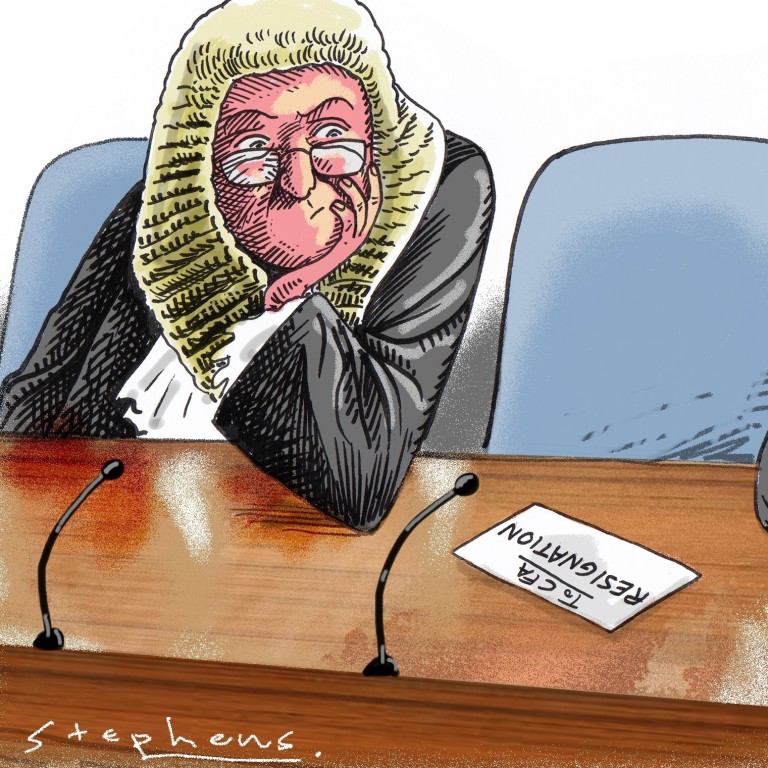

Will the national security law provoke an exodus of foreign judges from Hong Kong?

- The resignation of an Australian non-permanent judge of the Court of Final Appeal has sparked fears that other senior judges from overseas could follow suit. Were this to happen, the court could draw on a list of retired Hong Kong judges

The Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal came into existence on July 1, 1997 and, under the Basic Law, is vested with the “power of final adjudication”. It comprises the chief justice, the three permanent judges and the non-permanent judges. A quorum of the court comprises five judges, including the chief justice, the three permanent judges and one non-permanent judge.

The total number of non-permanent judges permitted by law is 30, although there are currently only 17, drawn from two lists. The first comprises former Hong Kong judges, and there are currently four of these. The second list consists of judges from other common law jurisdictions, of whom there are now 13. Of the overseas non-permanent judges, nine come from the UK, three from Australia and one from Canada, and they include the president of the UK Supreme Court, and his three predecessors, as well as several former chief justices.

The Court of Final Appeal, like the lower courts, enjoys the protections provided by the Basic Law, which stipulates that it “shall exercise judicial power independently, free from any interference”. The involvement in its work of eminent common law judges from overseas has enriched the judgments of the court, and enhanced its stature. It is well regarded throughout the common law world, in which its judgments are sometimes cited.

Although no reason was provided for his resignation, Spigelman was reported to have told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, which he chaired from 2012 to 2017, that he had resigned for reasons “related to the content of the national security legislation”. He did not, however, particularise his objections to the law for Hong Kong, which was enacted on June 30.

What is surprising, however, is that he chose to resign at this juncture, as the Court of Final Appeal will soon play a crucial role in developing the jurisprudence associated with the national security law. He has now deprived himself of the opportunity to participate in that process, although the remaining judges will undoubtedly step up to the plate.

Quite clearly, a resignation of this sort can have a destabilising effect, and it has predictably been seized upon by national security law critics. Indeed, the former leader of the British Conservative Party, Sir Iain Duncan Smith, immediately announced that the future of all the Commonwealth judges on the court needed to be examined, as their presence was simply giving “cover to what is a totalitarian regime”.

There have previously been calls from politicians in both Britain and Canada for their respective non-permanent judges to consider their positions, and Spigelman’s resignation will be grist to their mill.

05:50

What you should know about China's new national security law for Hong Kong

Although it is unclear whether the Australian government advised Spigelman to resign, what is indisputable is that it has displayed hostility towards Hong Kong since the national security law was introduced.

Since July, Australia‘s travel advice on Hong Kong has warned Australians they could be at “increased risk of detention on vaguely defined national security grounds”, and the government has also suspended its extradition treaty, offered a “pathway to citizenship” for up to 10,000 Hong Kong residents, mainly students, and urged businesses to relocate from Hong Kong to Australia.

Given this animus, it should surprise nobody if the Court of Final Appeal is also in its sights, and Spigelman will hopefully clear the air on this at some point.

Hong Kong government defends judicial independence after foreign judge quits

There are, however, signs that Spigelman’s resignation is a one-off, and that other judges will not be following suit, at least for now. In particular, Robert French, a non-permanent judge since 2017, and the chief justice of Australia from 2008 to 2017, announced that he would not be resigning.

He said: “I have the greatest admiration for the chief justice and other permanent judges of that court and for their commitment to maintaining its judicial independence. My continuance in office is a reflection of my support for their commitment and my belief in their capacity to give effect to it. I would not continue if I believed otherwise.”

04:20

Chief justice opens legal year with pledge to uphold Hong Kong’s judicial independence

Thereafter, on July 17, Lord Reed, the president of the UK Supreme Court and, since 2017, a non-permanent judge of the Court of Final Appeal, declared, somewhat ominously, that the Supreme Court would “continue to assess the position in Hong Kong as it develops, in discussion with the UK government”, thus opening the door to a possible British withdrawal, which would delight many of that government’s supporters, including Sir Iain Duncan Smith.

If, however, other overseas judges resign, or are otherwise prevented from serving, the Court of Final Appeal will undoubtedly bounce back. If it ever becomes necessary, the non-permanent judges can be drawn exclusively from the list of retired Hong Kong judges, which can be significantly expanded.

Indeed, it quite often happens that the fifth judge in Court of Final Appeal appeal hearings comes from this list, and to start using its non-permanent judges all the time would present no problems. It would, however, mean that the court would no longer have ready access to overseas expertise, which would be a pity.

In the meantime, the court must continue to do what it has done so successfully over the past 23 years, namely, to deliver justice and uphold the rule of law.

Grenville Cross SC is a criminal justice analyst