Why US-China relations will be poorer for Branstad’s exit as China ambassador

- The departure of Branstad, whose ties with Xi Jinping go back to the 1980s, may signal the end of personal diplomacy. And, with US-China relations cooling, his successor is likely to hold more hawkish views

To appreciate why Branstad’s departure is so significant, it is necessary to look at why the former governor of Iowa was selected as ambassador. Branstad’s home state played a starring role in Xi Jinping’s narrative and his rise to power.

According to Joe Biden, then the US vice-president, the return to Muscatine was suggested by Xi. He visited the same family that hosted him back in 1985 and heralded the impact this experience had on shaping his view of America and his future career.

Yet, like many things with Xi, the significance of Muscatine was embellished. His 1985 stay was not, as he described it, his first visit to the US.

He had in fact visited Washington in 1980 as an aide to Geng Biao, a top Chinese general. Xi’s position was so junior at the time that he did not appear on the protocol lists – perhaps why he prefers the Muscatine visit in his official biography as his first exposure to the US.

The difference between Xi’s narrative and reality did not matter to Biden, to the people in Muscatine, nor to US officials in 2012. They welcomed him warmly. He vowed to create better ties between Iowa and China during his leadership – which came as music to the ears of farmers of soybeans and other agricultural products.

01:47

US farmers brace for more pain as China halts US agricultural imports amid escalating trade war

Prior ambassadors to China under Barack Obama and George W. Bush – such as former Montana senator Max Baucus, former Washington governor Gary Locke, and former Utah governor John Huntsman Jnr – came from similar backgrounds and emphasised US trade priorities with China.

Instead, he is likely to feel forced to follow up on the anti-China rhetoric he has campaigned on and used to deflect criticism of his response to the coronavirus pandemic.

11:15

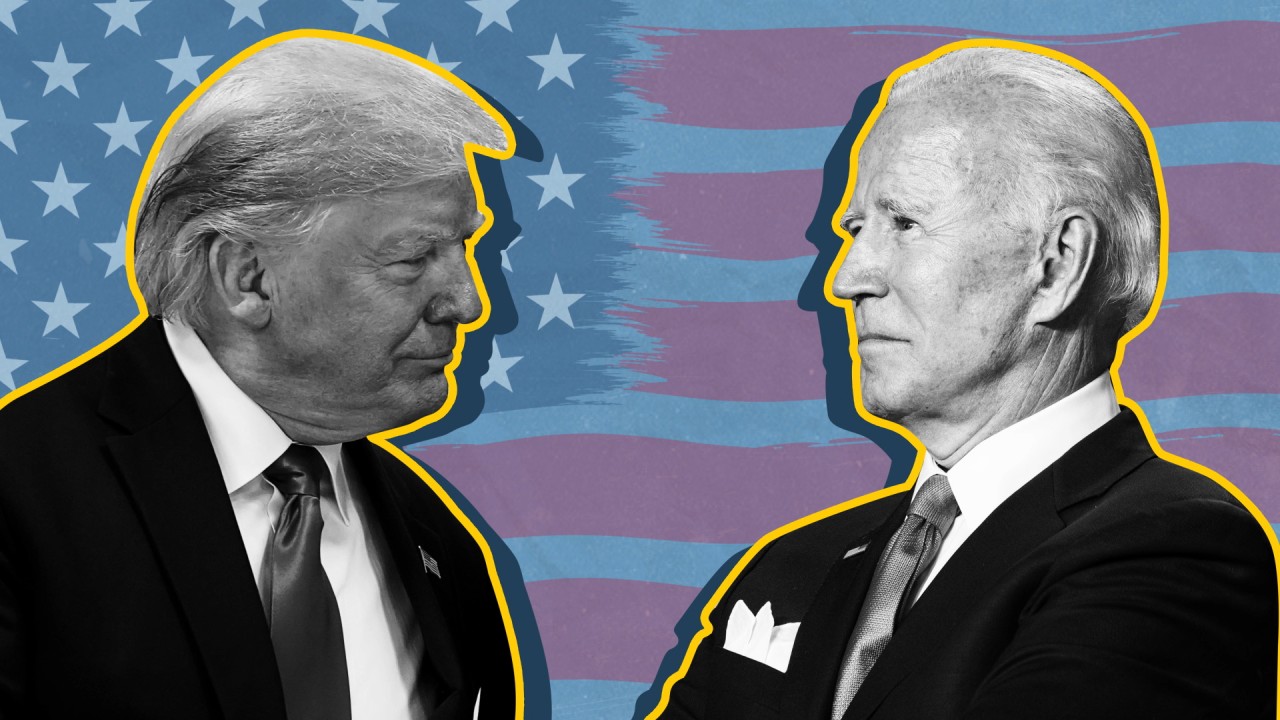

Trump vs Biden: The 2020 US presidential election

China should not anticipate a much better selection if Biden wins. He has also vowed to take a tougher approach to China, and he might select an ambassador with a human rights background, such as Suzan Johnson Cook, the former ambassador at large for international religious freedom, whom Chinese officials refused to meet in 2012.

We do not know, nor are we likely to ever fully understand, the rationale behind Branstad’s decision to leave. If Branstad is leaving to join the Trump campaign, then China should expect to hear him bashing China on cable news promptly after he returns.

This will be just another escalation of the increasing animosity between the US and China, which has affected journalists, diplomats and students in both countries.

With his departure imminent, it appears unlikely that he will try again to get his opinion published in China. The Chinese may well find that his words in his next position, where he will be untethered from both Chinese censors and the formalities of the ambassadorship, are far more damaging.

Chi Wang, a former head of the Chinese section of the US Library of Congress, is president of the US-China Policy Foundation.