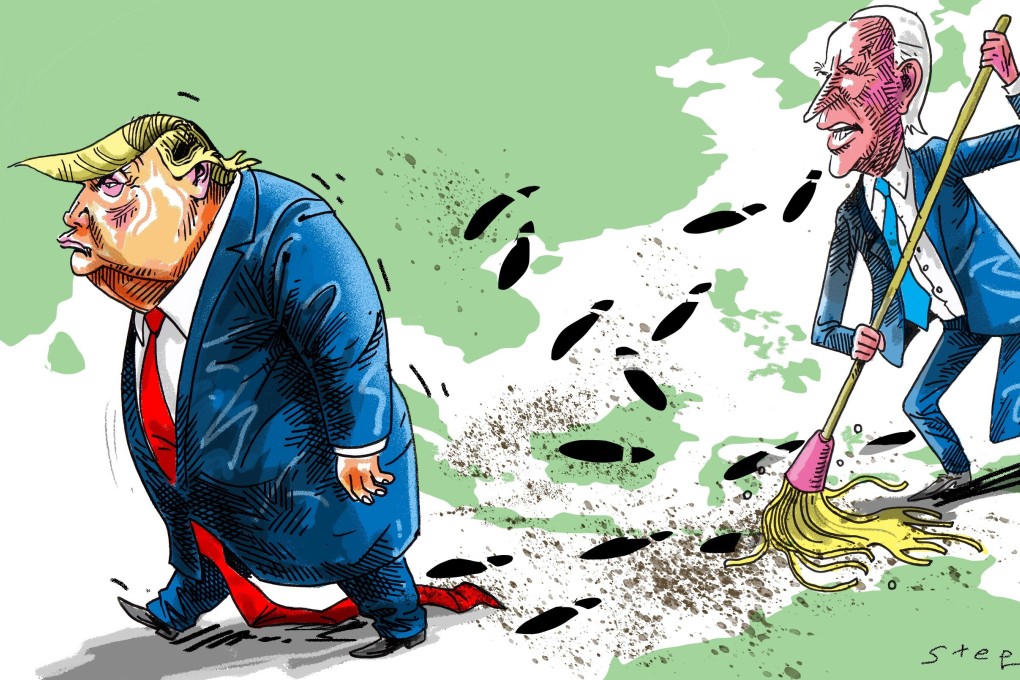

Opinion | What US allies in Asia need from the next American president

- Asian nations, for whom the Chinese threat is closer to home, would welcome a return to the US’ long-standing foreign policy traditions and global leadership instead of the transactional approach favoured by Trump

In a provocative essay for Foreign Policy recently, James Crabtree wrote that Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden has a credibility problem in Asia. “Officials in Tokyo, Taipei, New Delhi, Singapore, and other capitals have grown relatively comfortable with Trump and his tough approach on China,” he said. By contrast, Crabtree pointed out, Biden is seen to represent a softer and more conciliatory approach towards China.

Yet, while Trump has taken economic measures against China, the US’ allies in Asia need much more. In recent times, China has become increasingly aggressive towards its neighbours, and the efforts by the US and others to challenge China economically have not worked as a deterrent.

06:24

Explained: the history of China’s territorial disputes

China’s neighbours may need military support from the US, but Trump has proven unreliable on security commitments, even towards countries with whom the US has mutual defence treaties.