Opinion | Hong Kong must reindustrialise to reinvent its economy

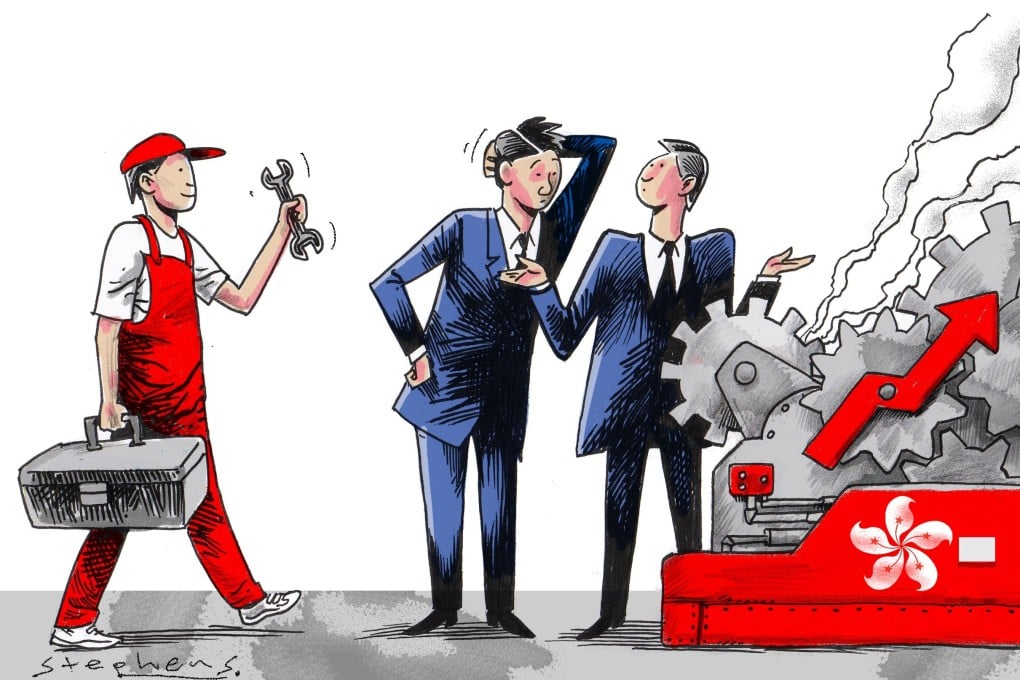

- With neighbour Shenzhen poised to pull ahead, Hong Kong needs an economic transformation of its own: it must end its reliance on the financial industry

- The city should focus on creating rewarding, good-paying jobs that benefit more than a few by upgrading its workforce and developing a new manufacturing sector based on science and technology

As US-China tensions continue to escalate amid the Covid-19 pandemic and a global trend of deglobalisation, Hong Kong’s role as an economic gateway between mainland China and the rest of the world is likely to shrink in the foreseeable future.

The four pillar industries identified by the government – financial services, tourism, trading and logistics, and professional services – managed to maintain a stable share of Hong Kong’s gross domestic product (about 58 per cent) only because of the continuous expansion of one industry, financial services.

05:25

Hong Kong's competitive edge questioned as Xi says Shenzhen is engine of China’s Greater Bay Area

But how long can Hong Kong continue to rely on finance, which has contributed to rising inequality in the city, as its growth engine? Can the city make itself more relevant in contributing to China’s economic development, like in the old days, besides simply being a financier?