A stronger China has no reason to seek a sphere of influence even as US power wanes

- China has no interest in replacing the US as the world’s dominant military and political power. In East Asia, the challenge is how Beijing and Washington, with their overlapping influence, can coexist

- The US suspects China is trying to drive it out of the region and has stepped up its provocations over Taiwan and the South China Sea, which risk testing the PLA’s patience

Does a stronger China need a sphere of influence? I asked myself this question when I came across the article, “The New Spheres of Influence”, in Foreign Affairs by Harvard professor Graham Allison. Allison argues that, after the Cold War, the entire world became a de facto American sphere. But now the unipolarity is over. The United States must share its spheres of influence with other great powers such as China and Russia.

I imagine for a moment where a Chinese “sphere of influence” might be. Not in Central Asia, where Russia’s influence is dominant. Not in South Asia, where India’s influence is paramount. Only East Asia looks likely, given its historical and cultural ties with China.

But, if a sphere of influence means a state has a level of exclusive control in cultural, economic, military or political matters, to which other states show deference, East Asia can hardly be described as China’s sphere of influence.

North Korea has developed nuclear weapons despite China’s disapproval. Japan, South Korea and Thailand are American allies. Some member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, such as Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia and Brunei, have territorial disputes with China in the South China Sea.

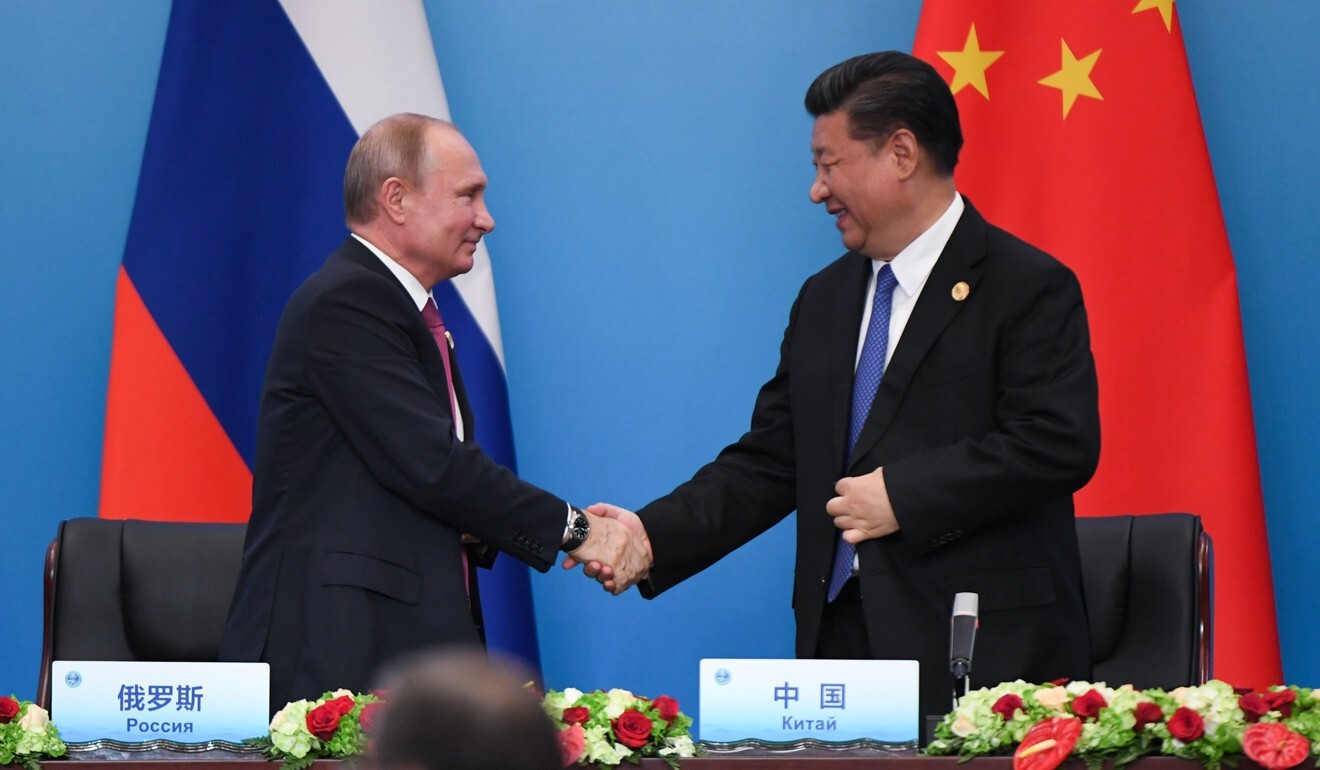

With Chinese and Russian as its official languages, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), which has no Western members, might look like a joint sphere of influence for China and Russia. But it has proven more inclusive than anticipated. Turkey, a Nato member, is a dialogue partner of the SCO. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan had even asked to join the organisation as a full member.

India and Pakistan became member states in 2017. The inclusion of two long-time arch-rivals could bring problems, but their membership also increases the influence of the organisation, which straddles the Eurasia continent, and strengthens efforts to tackle the so-called “three evils” of terrorism, separatism and extremism that have plagued the region.

But no international laws prohibit land reclamation, and some other claimants have done the same. China maintains that around 100,000 ships transit through the South China Sea every year without freedom of navigation problems. What China opposes are military activities against the interests of the littoral states in the name of freedom of navigation.

The Chinese government has repeatedly stressed that China would not seek to be a hegemon even if it became developed. Although this might sound like lip service to some, its assertion is backed by history. For 2,000 years, much of East Asia was part of the Chinese sphere of influence, but that influence was primarily cultural.

Influence and a sphere of influence are two different things. Today, China’s influence almost overlaps with that of the United States. Such influence will grow further since China is widely expected to surpass the US to become the world’s largest economy in terms of gross domestic product in 10 to 15 years. In other words, a global China is already influential enough to demand any spheres of influence.

This then invites two most important questions for the 21st century: how will the world accommodate China’s rise? And, what can China bring to the world?

Why Taiwan may be a key factor in China’s military modernisation plan

There is no guarantee the US could win in a military conflict with China in the first chain of islands stretching from Japan to the Philippines and the South China Sea. But should it lose, the consequence is not moot: it would lose prestige and credibility among its allies and partners in the region. The alliance would fall apart and it may have to go home. In that sense, only the United States can displace the United States in the Western Pacific.

Allison is right to conclude the illusion that other nations will simply take their assigned place in a US-led international order is over. But even if that means there are indeed spheres of influence in the world today, China should beware and stay away from them. They look more like perilous traps than power vacuums awaiting China.

Senior Colonel Zhou Bo (retired) is a senior fellow at the Centre for International Security and Strategy, Tsinghua University, and a China Forum expert