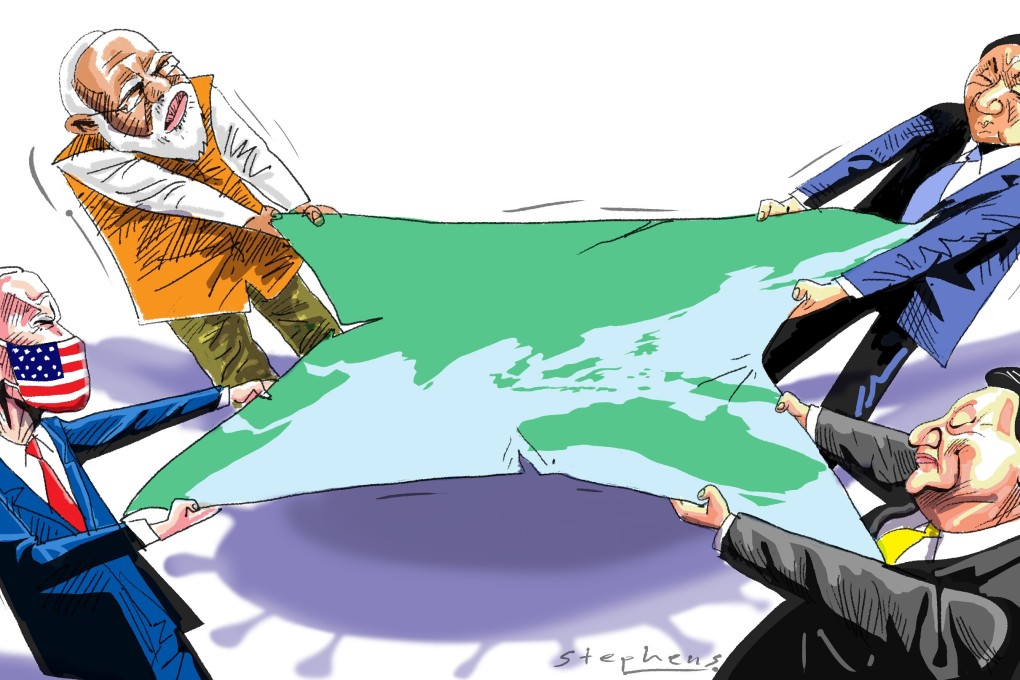

Opinion | How Indo-Pacific tensions reflect a post-coronavirus new world order of conflict and contradiction

- The emerging global order of 2021 and beyond will be more of a ‘contra-polar’ world, where contradictory policy pursuits and contrarian impulses are the norm

- China’s ability to avoid becoming the glue that provides cohesion to the US-India partnership will shape the contours of the next decade’s geopolitics

When the curtain finally comes down on 2020, it will have a distinctive annus horribilis tag to it, given the malignant bleakness of the pandemic-tainted year.

Massive disruptions to the normal global rhythm resulting in nearly 1.6 million Covid-19 deaths across the world, colossal economic losses and still-unassessed, pandemic-induced consequences will challenge state and society in the rebuilding to come.

The macroeconomic assessment of 2020 is definitive. The International Monetary Fund has estimated overall global GDP will fall 4.4 per cent, with emerging markets and developing economies expected shrink by 3.3 per cent and advanced economies by 5.8 per cent.

However, 2020’s impact on geopolitics is more complex and tangled. It is exacerbated in no small measure by the policies of US President Donald Trump’s administration and the actions of President Xi Jinping’s team in Beijing.

06:04

US-China relations: Joe Biden would approach China with more ‘regularity and normality’